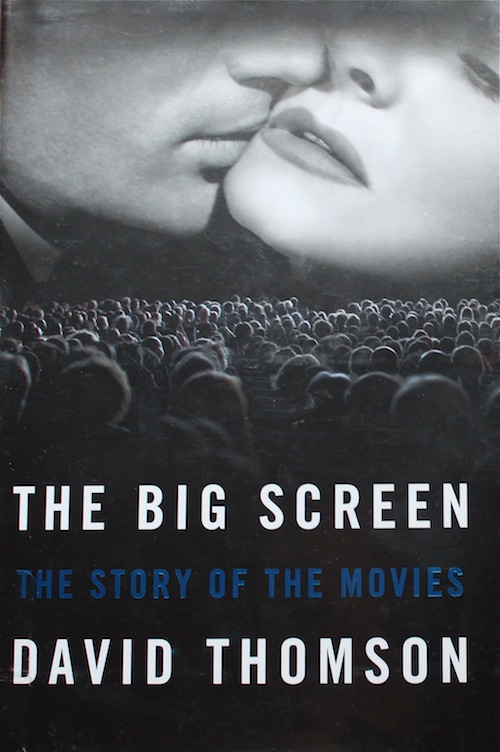

The Big Screen, The Story of the Movies

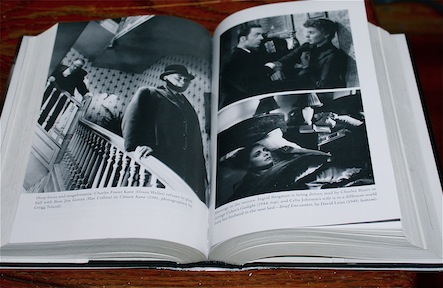

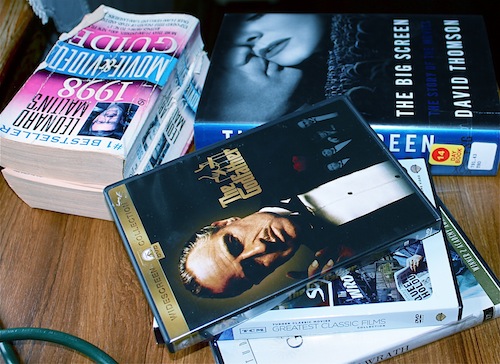

This is a big book, a comprehensive book, a book written with evident knowledge, wisdom, affection—and apprehension. Thomson, well known and well regarded, seventy-two years old as of the 2012 publication date, is, as the dust cover reminds us, “renowned as one of the great living authorities on the movies.” (He wrote The New Biographical Dictionary of Film, 2010.) The book’s subtitle is somewhat misleading. Yes, all of the great films are recorded and discussed, along with the not-so-great, the curiosities and even some bombs, and, yes, the bulk of this 600-pager is on cinema as traditionally defined. But Thomson, here in this second decade of our twenty-first century, is reaching towards something else, something having to do with the big screens, of course, but also something to do with the proliferation of the many, many smaller screens ubiquitous in our lives today; and he is mourning what he knows must eventually come about: the end of experiencing with others publically the magic of light projected from real film stock onto a large silver screen. Thus his apprehension.

Throughout The Big Screen, Thomson keeps seeking for us—and himself—the real, the true meaning behind all of these decades of interest and love we have for film: “Is this a movie? Is it for us? Why are we looking?” He also wants to grasp, for once and for all, how we are impacted, culturally, morally and politically, by movies. Thomson keeps inquiring: “I know this leads into infinite and unanswerable questions on the influence movies have had, but that is the central task of this book, and I will not dodge it just because the ‘evidence’ is scattered and contradictory. Just because it’s so hard to measure the impact of movies quantitatively does not meant the impact is a myth.” Amidst what may be expected, encomiums for films both cherished by or surprisingly unknown to the general movie buff, the fan of Turner Classic Movies perhaps, Battleship Potemkin, Citizen Kane, Hiroshima Mon Amour, Casablanca, Meet Me in St. Louis, Double Indemnity, Pulp Fiction, Casino, Mulholland Dr. (Thomson is not hopelessly moored in the past), are perceptive commentaries on pornography, politics, television, video games and Facebook. (A quick aside concerning the above-mentioned movies: I love his comment, “If you look at Pulp Fiction now you already feel some of the nostalgia you might get watching Casablanca.”)

Throughout The Big Screen, Thomson keeps seeking for us—and himself—the real, the true meaning behind all of these decades of interest and love we have for film: “Is this a movie? Is it for us? Why are we looking?” He also wants to grasp, for once and for all, how we are impacted, culturally, morally and politically, by movies. Thomson keeps inquiring: “I know this leads into infinite and unanswerable questions on the influence movies have had, but that is the central task of this book, and I will not dodge it just because the ‘evidence’ is scattered and contradictory. Just because it’s so hard to measure the impact of movies quantitatively does not meant the impact is a myth.” Amidst what may be expected, encomiums for films both cherished by or surprisingly unknown to the general movie buff, the fan of Turner Classic Movies perhaps, Battleship Potemkin, Citizen Kane, Hiroshima Mon Amour, Casablanca, Meet Me in St. Louis, Double Indemnity, Pulp Fiction, Casino, Mulholland Dr. (Thomson is not hopelessly moored in the past), are perceptive commentaries on pornography, politics, television, video games and Facebook. (A quick aside concerning the above-mentioned movies: I love his comment, “If you look at Pulp Fiction now you already feel some of the nostalgia you might get watching Casablanca.”)

On pornography: “Like so much movie over the decades, hard core is sensational but monotonous. . . . It resembles a weekend in Las Vegas, and breeds as many dismayed losers.” He also tells us that he cannot help looking at these films critically: “They are usually very well lit. . . . The camera prefers extended takes. There are intricate, probing movements [Ouch!] to get a better view. . . . The shooting style and its relevance to the action is invariably more fluent and interesting than one finds in today’s average feature film.”

On pornography: “Like so much movie over the decades, hard core is sensational but monotonous. . . . It resembles a weekend in Las Vegas, and breeds as many dismayed losers.” He also tells us that he cannot help looking at these films critically: “They are usually very well lit. . . . The camera prefers extended takes. There are intricate, probing movements [Ouch!] to get a better view. . . . The shooting style and its relevance to the action is invariably more fluent and interesting than one finds in today’s average feature film.”

On politics: Thomson is now, and has been for some time, established in America, but his roots are British. Because of this, his views have an edge, a detachment. He comments on the various codes and censors and their eventual surrender. He talks about how movies had the force to change lives in both large and small ways. An example of the latter is his take on women’s fashions: “In the early years of filmmaking, most people bought clothes out of necessity, not for pleasure or self-expression . . . but movies cheerfully celebrated wealth and style and brought them within a more common range.” Concerning the former, Thomson takes a four-page look at the American presidency from Kennedy to Obama—focusing on the former movie star Reagan. “The office of the presidency has been blurred and inhabited by television coverage and spin, and by that Reagan ease. How can a president be so relaxed? He doesn’t remember everything.”

On television: The highlight here is Thomson’s reverence for Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. He not only delights in their sitcom, he ponders the way in which their guest stars, movie idol William Holden among them, played into the overlap of both “real” reality and the reality of TV itself, linking this concept to the reality shows of the last decades. Thomson also applauds Arnaz’s perceptive decision to shoot the episodes on film rather than on kinescope, his three-camera “factory system of moviemaking,” and his solid business acumen and sound judgment that made for the opening and the success of Desilu productions. Thomson also has good words to say about, among other shows, The Sopranos.

On television: The highlight here is Thomson’s reverence for Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz. He not only delights in their sitcom, he ponders the way in which their guest stars, movie idol William Holden among them, played into the overlap of both “real” reality and the reality of TV itself, linking this concept to the reality shows of the last decades. Thomson also applauds Arnaz’s perceptive decision to shoot the episodes on film rather than on kinescope, his three-camera “factory system of moviemaking,” and his solid business acumen and sound judgment that made for the opening and the success of Desilu productions. Thomson also has good words to say about, among other shows, The Sopranos.

On video games: “One came off these games buzzing. The screen had found a new way of being. And today some people sometimes play the latest version of those games in front of the movie.” Thomson also tells us that in 2011, Adam Sandler’s Jack and Jill grossed “about $26 million” while in the same month of that year, the game Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 had earned “$400 million in immediate sales.” Another turn for Thomson’s anxiety?

On Facebook: “This is a prodigy of our time . . . as wondrous as the movies seemed in the 1920s.” The guru of Facebook, Mark Zuckerberg, is worth over $17 billion, and Thomson suggests that there should be some responsibility inherent in this enterprise. He can only speculate as to the future ramifications of Facebook and the like.

The Big Screen, then, is lost somewhere between a traditional book on movies, ala Pauline Kael’s When the Lights Go Down, and, in the light of our contemporary, nearly futuristic, world of pixels, instantaneous uploading, infinite apps, immediate downloading and ravenous streaming, an appeal to the future of the traditional cinema, a realization of its fragility and an apprehension of its probable demise. Now for a word from our sponsor.

Copyright 2013, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter