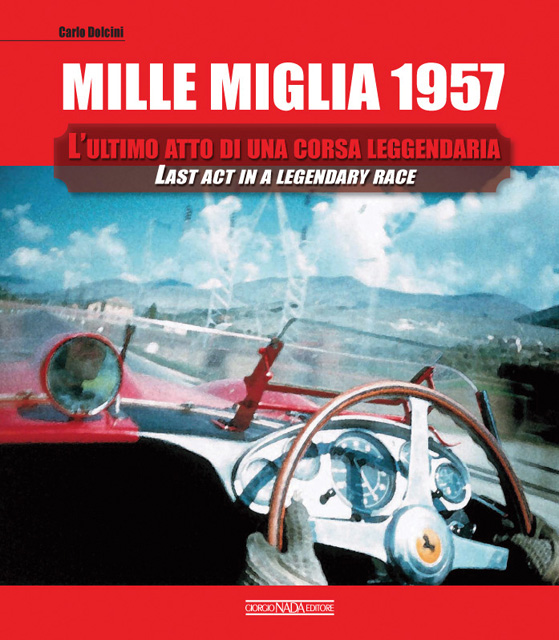

Mille Miglia 1957: Last Act in a Legendary Race

“As he was just about to re-start, sent on his way with a happy wave from Linda, his eyes are two sad cracks. One senses the return of that internal anguish which had surfaced a few hours earlier at the Ravenna stop. He had begun to die and he knew it.”

(Italian / English) Did he really know that? Would you have seen that in his eyes in the photo (p. 81) the excerpt above refers to? Or is the author, with the benefit of hindsight, reading into it?

If you know nothing about the Mille Miglia, especially that year’s Mille, the one that because of what was to happen next would be the last one for 20 years, such word pictures will draw you in, and that, really, is what a good book should do.

If you do know the sad story of the 24th running of the Mille that would see Alfonso de Portago—whether he did have a premonition that “he had begun to die” or not—perish at the wheel of his Ferrari (and worse, taking 11 others with him), then you’ll find many instances in the book where events that have yet to come to pass are “read into” the story as it is unfolding, ascribing to the protagonists thoughts, feelings, knowledge they could not have had at the time. Chalk it up to Dolcini’s writing style. He certainly knows the raw facts and hard data, and has several Mille and other motorsports books under his belt, but this sort of “dramatization” does amp up the volume.

One thing that is very much a matter of personal style is his ornate way of building long, complex, nested sentences, often enough using quotes within quotes, all of which forcing the reader to read certain sentences three times, ten times, only to still wonder if they got it. Maybe Dolcini’s other day job, that of Professor of History of the Philosophy of the Middle Ages, gets in the way here. The English translation, too often a dubious aspect of this publisher’s books, struggles mightily with this and often enough, by too slavishly adhering to the Italian structures, fails.

This really only means you have to put some work into this book to get the most out of it. A quick sidebar: this book came out in 2011, as the first of a series that was to cover all 1947–57 races. We purposely didn’t review it then, waiting instead for further installments. Nothing happened, except a companion volume in 2013 (The Minor Classes: The Unsung Heroes of the Mille Miglia) that covered those classes in 1957 that were not considered in the present book which only looks at the Over 2 Liter Sports and GT Class.

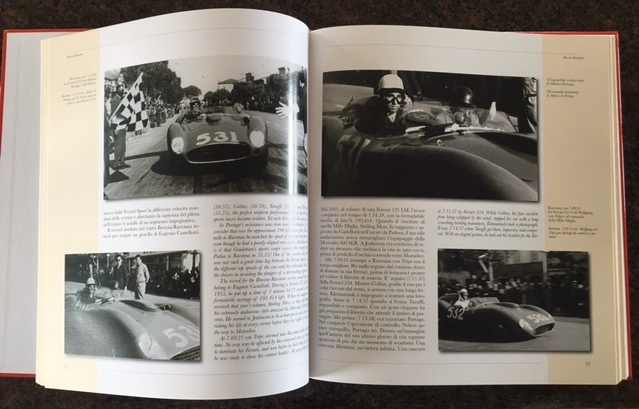

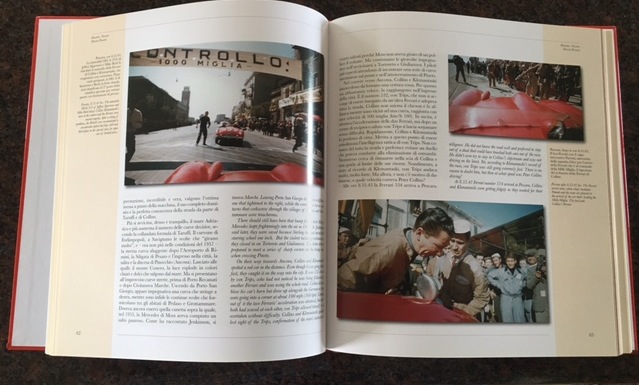

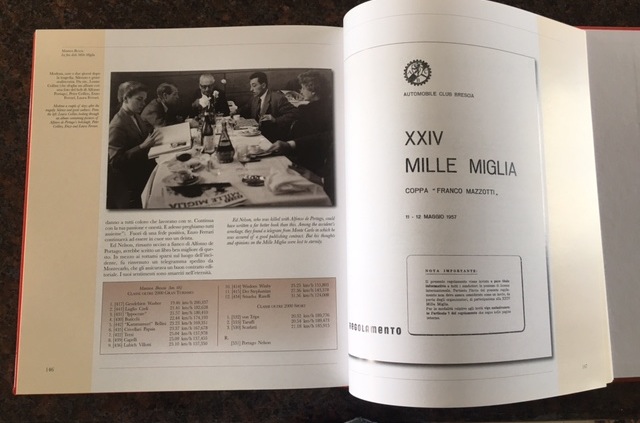

Given the historical importance of the 1957 tragedy it is no wonder that the topic has been explored many times and in many ways. In terms of basic facts there is nothing fundamentally new here although Dolcini does early on refer to a “previously unpublished legal file of the Portago accident.” (This quote, if you missed it, is an example of the sort of English that lacks clarity.) The illustrations, some even in color, are well chosen and of decent size and reproduction quality. Some may very well be new to the record (credits are listed at the back) although it might only look that way because of how the way they are cropped yields a different image area. Quite a few include significant others (when is the last time you’ve seen a photo of Laura Ferrari [above]??) which is a nice touch in a story that, at its core, is about the human side of the cruel sport.

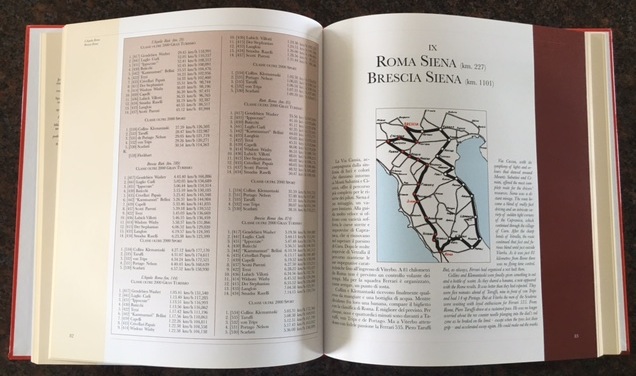

Each stage is covered in its own chapter, replete with a map (place names print a bit fuzzy) and data tables. For the Appendices you’ll have to cozy up to your Italian friends: the entire 11-page booklet of Mille Miglia ragulations [sic], starting order, overall results and class results, and a Bibliography by chapter (which, therefore, should probably be thought of as Sources) are in Italian, except for heads.

Even without Dolcini’s efforts at adding color to the story by dwelling on the inner lives of the protagonists, the pressures they are under become abundantly clear—financial, technical, philosophical, the disparity in age and temperament and their station in life. Information, misinformation, delayed information all play a role in manipulating especially the drivers. Their seemingly reasoned choices are as compromised as off-the-cuff judgment calls. And so de Portago sees no other choice than to keep on driving, overdriving, and so to perish. Morituri te salutant! “Those who are about to die salute you” said the gladiators to their Caesar as they took their places.

In historical terms, this is an exceptionally rich story, and here it is told in a rich way.

Copyright 2016, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter