Fast on the Sand: The Daytona Beach Land Speed Record Runs of 1928

by Aldo Zana

by Aldo Zana

“The reader will find the true facts narrated with a level of detail never before presented, based strictly on period sources thoroughly crosschecked.

Research initiated some 40 years ago in the U.S. and UK brought back to the surface photos and some other either unpublished or forgotten documents, including a detailed factual report on Frank Lockhart’s fatal accident on the beach. The truth about the accident and the aftermath of the young driver’s death told in these pages amends the load of incorrect news and indecent theorizing aired immediately after the event and duplicating by too many authors without checking any period source.”

Interesting topic. Innocuous title. A seasoned Italian motor historian revisiting the well-trodden ground of an Anglo-American rivalry almost a hundred years ago. Written with just the right dose of drama to engage the imagination. All right then.

But, wait, there’s more . . . if you skipped the intro quote above, read it now. What the title doesn’t say is that this book is not merely a ripping story but a critical look at the quality of the reporting during and especially after, even decades after the fateful season that would claim the life of American driver Frank Lockhart during an LSR attempt. In other words, the canon of recorded history needs revision.

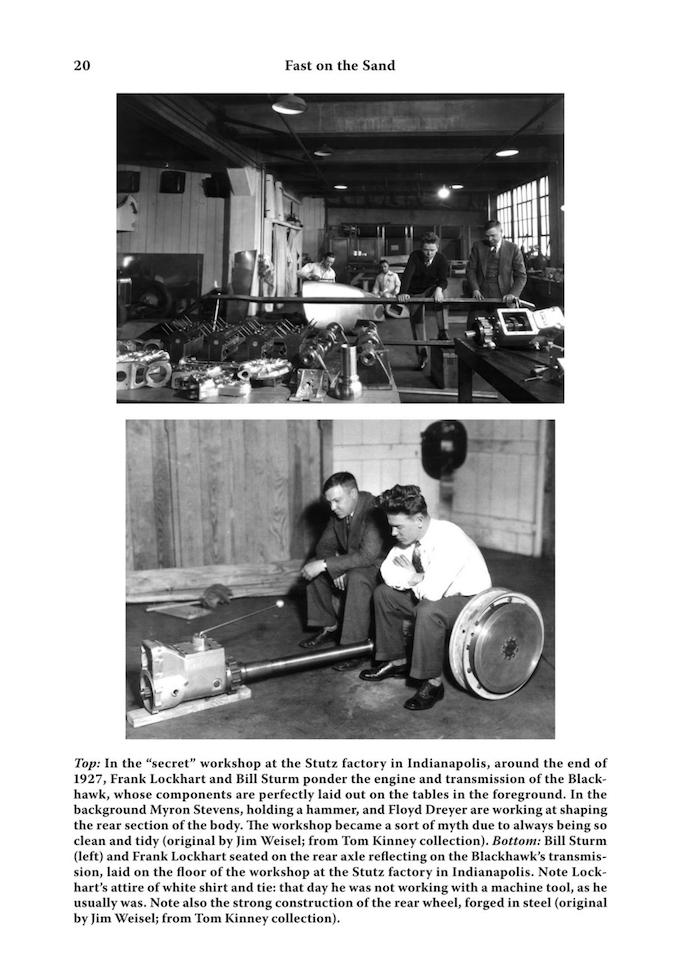

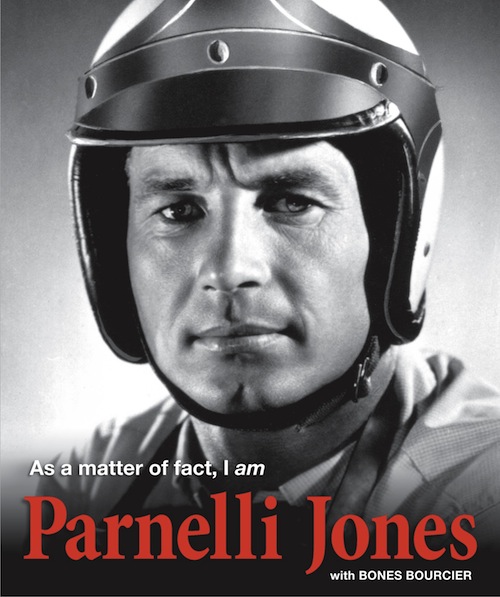

Some assembly required. Lockhart, the fellow in the white shirt, was so capable an engineer that Stutz put him on their engineering staff.

If you are new to the subject, this is a fine and cohesive book, in the typical fashion of books by this publisher: rather Spartan in presentation (quantity/size of photos etc.) but fully girded for battle with notes and references and such.

Lockhart is of course only one of the protagonists of this story, alongside countryman Keech and one of the British LSR heavyweights, Campbell, but it is the Lockhart factor that dominates 1928. An entire book had been devoted to him, in 2012, Frank Lockhart–American Speed King (Zana: “the best and most complete”) and it too found the discrepancies in the existing coverage overdue for critical examination. Further, 1928 was the first year LSRs set in the US were fully sanctioned by the international regulatory bodies, a complicated tug of war that the book also explains.

We used the word drama above. Indeed the book is structured thusly: Prelude, Act 1, Intermission, Act 2, Epilogue. Well, there’s an Aftermath but that is simply a synopsis of the six years following. If you know the existing literature on the LSR (or scrutinize the Bibliography) and in particular the three men in 1928 you will find that Zana does too, able to quote chapter and verse which he actually does at length and, more importantly, within a framework of context.

In a way, the book is like a courtroom proceeding: follow the evidence where it leads, juror dear. Whether you end up convinced or not that Zana makes the better case, the presentation is clear, precise, compelling. While he mentions it early on in the book he does not elaborate: “The author in the early 1970s had the rare opportunity to meet in person a few surviving witnesses of the 1928 Speed Trials and to share documents, images, and know-how with other experts.” That’s 50 years ago; just as well that Zana took his time: he received new, or at least unpublished, information into the 2000s.

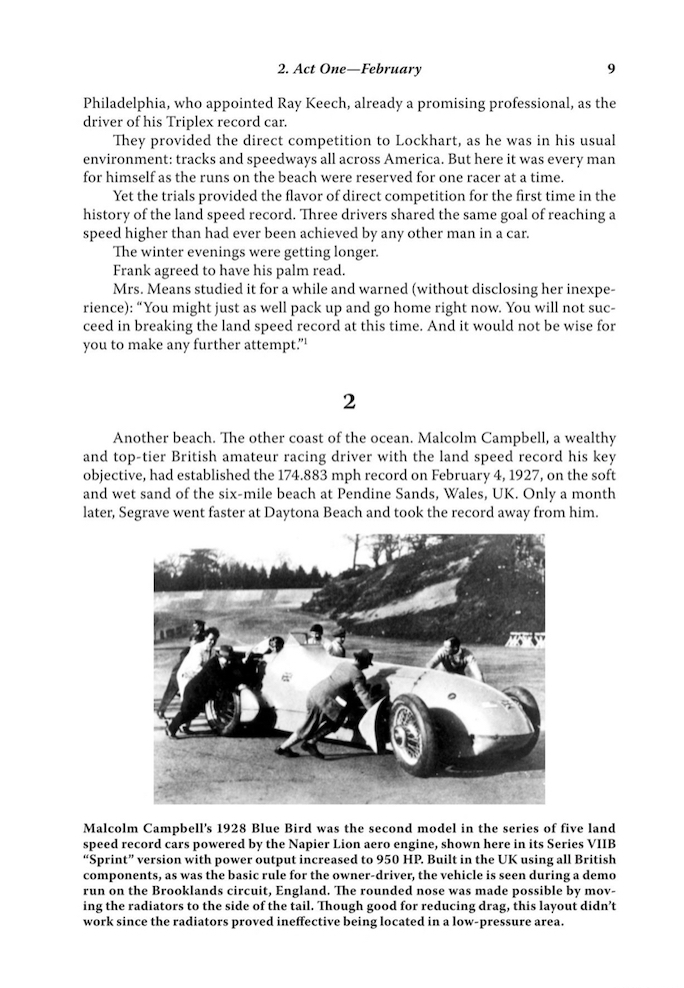

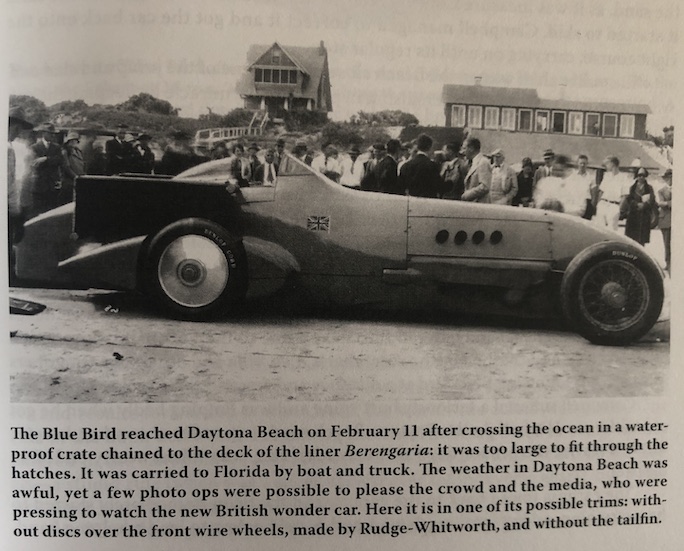

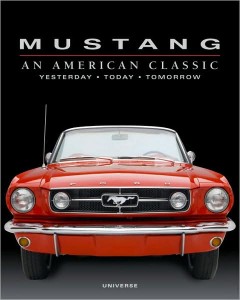

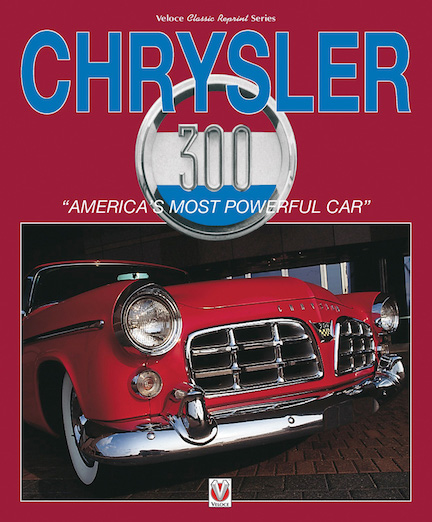

This image gives a good sense of how large Campbell’s Blue Bird was. And just imagine: 950 hp—in 1928, thanks to a Napier Lion aero engine. Five years later that number would be 1400 hp and higher. And a year after that, 2500 hp!

The use of the word “amend” in the intro excerpt above begs the question if it was just a handy English word the author happened to have at the top of his head or if it is used with the exact specificity its formal definition implies: “making minor changes in (a text) in order to make it fairer, more accurate, or more up-to-date,” the emphasis being on minor. The criticisms Zana lays out are anything but minor and his language is quite unambiguous. Of motoring writer Griffith Borgeson, whose arch reputation gave his pronouncements enormous weight, he writes: “The LSR was not the paranoid obsession narrated by B. and the authors who, for decades, copied him.” And a few pages later: “It has to be said that the diagram of the accident published by B. and other authors is rather too simplified to be relied upon.”

From motorsports politics (regulations, funding etc.) to local politics (tourism, boosterism) and from national animus to LSR car design and timing trap technology, the book covers a lot of ground. It boggles the mind to think that chasing record speeds, an inherently dangerous activity, on a surface as inherently unpredictable and constantly changing as sand was ever deemed a good and safe idea—yet it had been in practice for over a quarter century by 1928. While Daytona Beach was supremely convenient in terms of ease of public access and nearness to the comforts of civilizations, the ever increasing speeds would soon force a change in venue: salt flats, even if their very vastness means they’ll be in the middle of nowhere.

Zana’s way of building the story has a certain internal drive and it’s probably best read in one continuous sweep and then go back for a slower second pass to internalize the myriad of detail on the forensic side.

Four Appendices explore aerodynamics, two of the record cars, and all of the engines.

Copyright 2022, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

TAKE 2

Sometimes a book inspires more than one reviewer to render an opinion. Everybody does see different things, or sees things different so every now and then we may post such musings for your enlightenment.

For just shy of 200 years Daytona Beach, Florida has been associated with the automobile and speed. These days it is most often NASCAR or the 24 Hours of Daytona we read and hear about. But “in the beginning” all the action was straightline and on the sand. Later there would be a sandy road course. With this book the focus is on one specific year, 1928, and a straight line over a specified mile length timed course, not including the stretches of beach needed for the approach run-up and deceleration run-out.

That 1928 year, for those not versed in land speed contests of that era, was notable for its three contenders vying for the record; two American and one British each with very different vehicular approaches. This book’s focus is on the activities, the people, and the cars of those Daytona Beach Land Speed Record Runs of 1928.

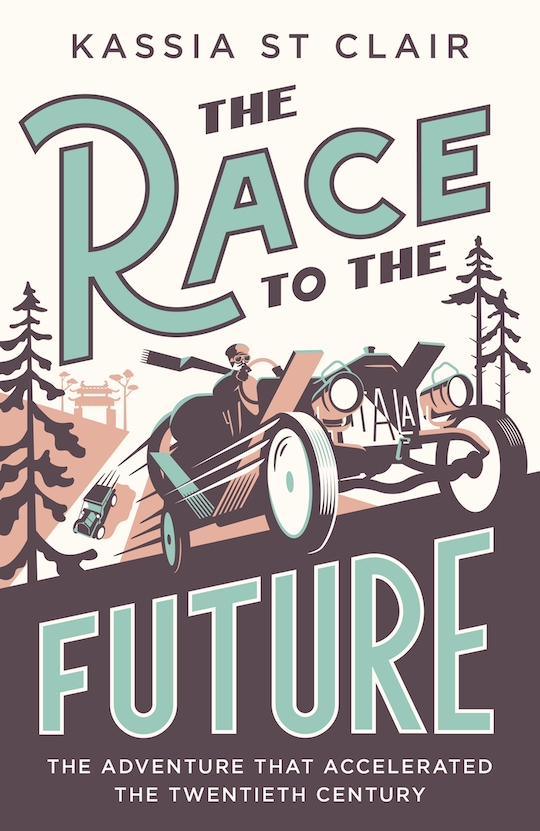

The runs attracted large numbers of spectators who paid fifty cents apiece. As well, a myriad of media from both sides of the Atlantic were in attendance. Thus this book’s author, Italian motoring journalist Aldo Zana, had a large quantity of period reporting in both American and British newspapers and journals to draw upon in addition to a number of books focusing on a specific car or person published since as his bibliography and chapter end notes attest. In fact, the attention-grabbing cover art is credited to the British-publication The Motor showing that country’s contender, Malcolm Campbell in his Blue Bird, racing along the sand. Pity though, the artist isn’t named.

That said, while Zana quotes liberally from period news articles he also passes judgment on some of the reporting labeling it “fake news” with a frequency that became annoying to this reader. It has become a loaded and polarizing expression, and more than once I found myself wondering whether Zana was expressing the sort of cynicism we have come to know all too well from the realm of politics or attempting to convey that whatever he was commenting on was indeed flawed and incorrect reporting.

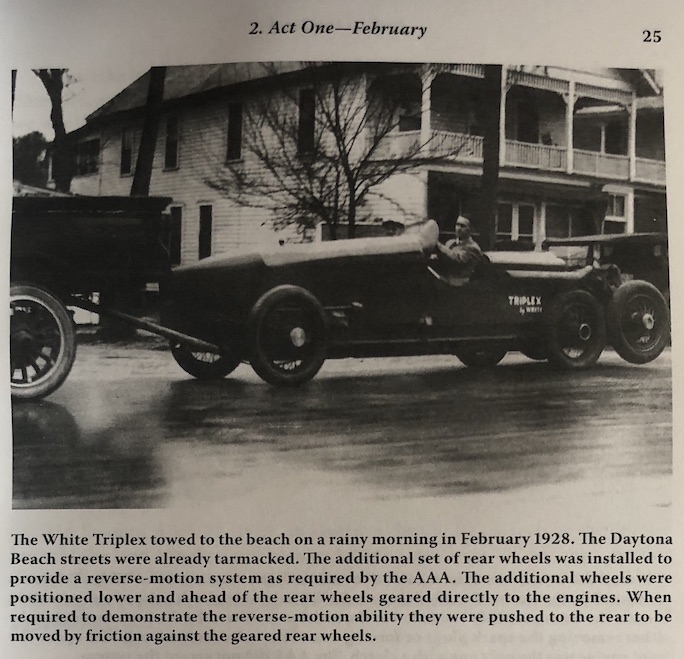

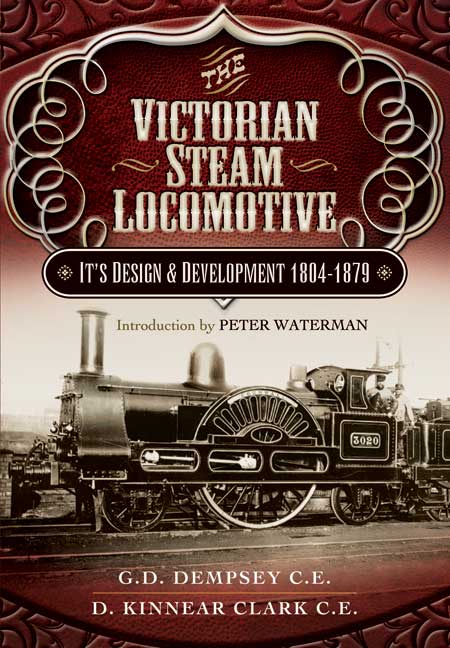

Who needs a reverse gear when you can use a third axle instead? That’s not the only odd feature of the Triplex.

The lone entry from the other side of the Atlantic was Malcolm Campbell driving the car he conceived and had built which he called Blue Bird. The two American entries couldn’t have been more different. One was the massive and unorthodox Triplex. Horsepower was the only thing that mattered to Jim White who had it built powered by not one, but three Liberty aircraft engines with Ray Keech hired to drive. Frank Lockhart, who designed, constructed and drove his entry, took the opposite approach with his lithe and graceful, aerodynamically clad Stutz Black Hawk.

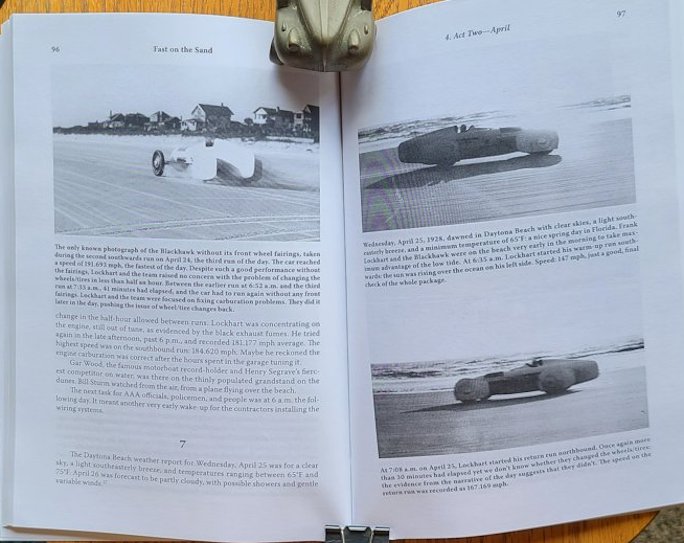

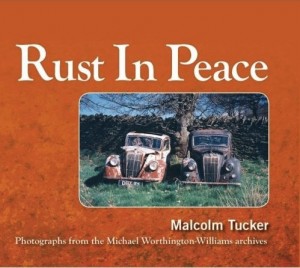

Three views of the Stutz Black Hawk underway. The one at top left is the only known image of it running without its front wheel aero fairing.

Zana has organized his narrative chronologically giving the reader almost a day by day accounting of the 1928 events with all their drama and action interspersed with disappointing days when winds blowing across the track and corrugating the sands of the heretofore flat beach made any runs impossible. The engineering details and specifications of the cars Zana tucks into the appendices which permits his narrative to keep moving forward. If you know the story, you’re aware of its tragic conclusion. If you don’t know, I’ll leave it to you to read and learn for Zana then offers a concluding chapter he titles “Aftermath — 1929-1935” because, of course, land speed runs would continue right up to current day albeit no longer on the sands of Daytona Beach but rather Bonneville, Utah’s Salt Flats.

It’s an interesting read especially for those unfamiliar with those 1928 events.

Copyright 2022 Helen V Hutchings (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter