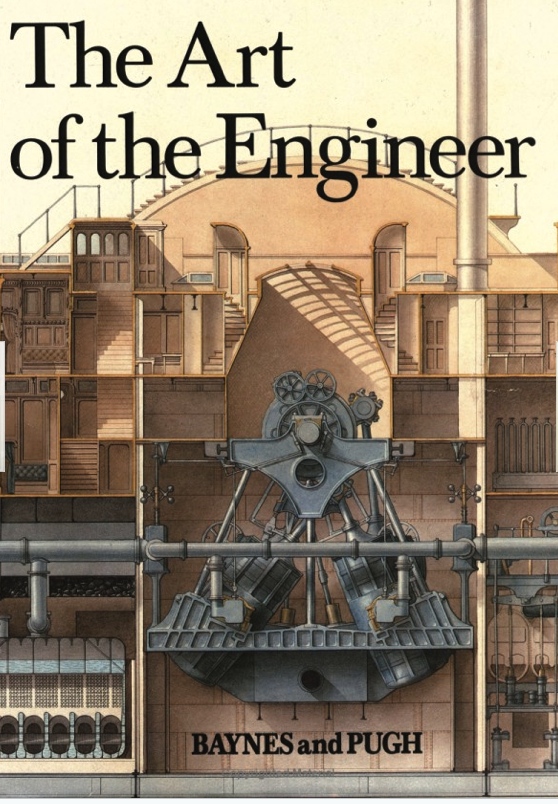

The Art of the Engineer

by Ken Baynes and Francis Pugh

by Ken Baynes and Francis Pugh

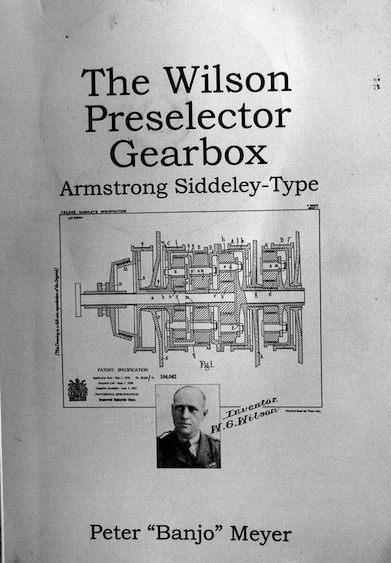

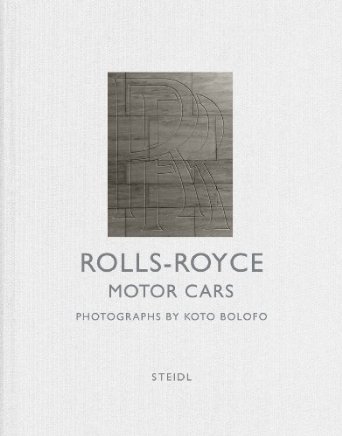

Nothing as powerful as a revolution happens without a plan. A “plan” in the most literal sense is what made the Industrial Revolution possible. Plan in the context of this book refers to the scientific and technical illustrations that precede the actual building of things. Rooted in the Renaissance and refined in the architectural and naval draftsmanship of the 16th and 17th centuries, the engineering drawing reached new heights of accuracy, both in terms of meaning as well as in execution, during the Industrial Revolution.

Sadly, many, if not most, of the architects of such plans have been lost to anonymity and obscurity. Only late in the 20th century have there been attempts to rediscover the work of our industrial and pre-industrial forebears and examine not only the impact of their work but how they actually went about their work. Precious few volumes have been devoted to the subject of the engineering drawing and it seems that nothing on the scope or scale of this book existed prior to the 1978–79 landmark exhibition by the Welsh Arts Council of working drawings. Indeed it was that exhibition that provided the impetus for this book, rich with expertly photographed drawings from the 13th century to the present.

From the Newcomen engine to submarines and gliders to cars, this book shows examples of the art of technical drawing. Although these drawings are beautiful to look at, as fine art and entirely without regard to their application, it is important to remember that “looking pretty” is not their ultimate purpose. They are tools in no less a sense than hammer and chisel. If a drawing takes the place of instructions, devised by one person and translated into action by another, it must convey its message with unambiguous precision. It is a form of coded communication, more rigid perhaps than even language itself. Its exactitude enables the vision in the inventor’s or architect’s head to remain intact as it travels via a drawing on flat paper to the mind of the builder who will “reconstitute” the original vision in three-dimensional form. Representing physical relationships of both static and dynamic components in such a way that they can be fabricated and assembled to produce a working mechanism, repeatedly and consistently, requires of the inventor not only the ability to conceive of the idea in the first place but then to have the skill to communicate it to the builder. Written language, for this purpose, is inadequate and inefficient: “a picture is worth a thousand words.” Therein lies the art and the craft of the technical drawing. Its lines are as simple as possible and as complex as the project at hand requires.

The engineer’s axiom, “if it looks right, it is right” applies to the book itself. Crisply bound in blue cloth, this is an edition that will sit proudly on any desk. From the first page, the care given to this subject is apparent. The text has been generously set to invite the reader, offering a chronological survey of the state of transportation and manufacture at this critical epoch and a closer look at some of the major figures and events that shaped our present state. No corners were cut, no expense appears to have been spared when it comes to the treatment of the actual drawings illustrated. Reproduced in rich color where appropriate, and always at a suitable size not only to create a page that is pleasing to look at, but to do proper justice to the original work.

The book’s only peculiarity—its overly tall shape—seems to beg that, should we find the wherewithal to put this volume down, drag our eyes from the generous pages, pull our minds from the coal-fueled haze of nineteenth century Europe, we do not tuck this book away neatly in the bookshelf. This one stays on the table.

This book was first published in 1981 with ISBN 0-7188-2506-3 by Lund Humphries Publishers Ltd.

Copyright 2009 Rodney Bender/Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

(Reviewer Bender is a fine artist and print designer and in his own work grapples with the same issues of clear communication as the draftsmen in this book.)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter