The Wilson Preselector Gearbox, Armstrong Siddeley-Type

Where was this book when I needed it?

A callow youth in 1963, I had recently been seduced by the beauty of a 1937 Riley 12/4 Continental Touring Saloon, but its pre-selector gearbox had promptly suffered a derangement. Since the purchase price had absorbed the last of my grandfather’s legacy, qualified professional help was beyond my resources—apart from a garage business that had retained some knowledge of these gearboxes and was thus able to extract the broken component and give me three indirect gears.

The previous owner had enlisted, ahem, specialists to rebuilt the gearbox and they had welded, badly, the Top Gear Pull Rod. Worse, they had parts left over . . . never a good sign . . . and so the absence of spacing washers gave me years of trouble when the gearbox was expected to transmit enough drive to climb a hill. Eventually I was able to find an engineer who knew these gearboxes from his work on the local buses, and he rebuilt mine properly using such new bits I was still able to find at the local Jaguar agency, previously Riley and Armstrong Siddeley.

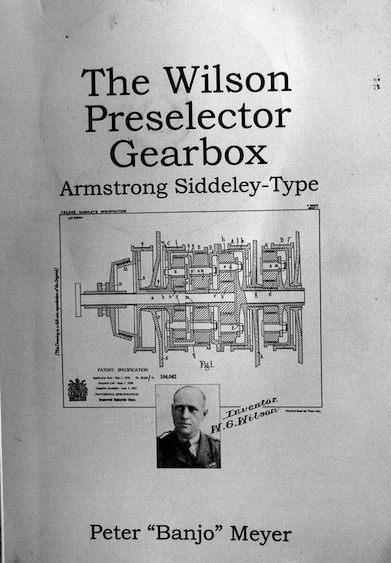

Now to “Banjo” Meyer’s book. At the 2011 Riley Register’s annual Coventry Rally, my wife was intrigued by this gentleman and his stall, and decided that I needed his book. With various personae as salesman, publisher, jazz musician, composer, band leader, car restorer and racing driver, he wrote this book in his native German, and it has been competently translated into clear English.

It comes with an informative DVD produced by Holger Lübcke, but with a caveat: “All information given without guarantee and subject to error.” So far, I haven’t found even a typo.

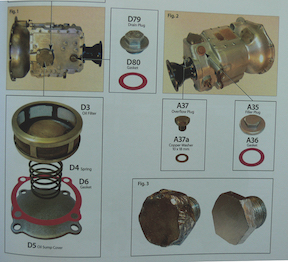

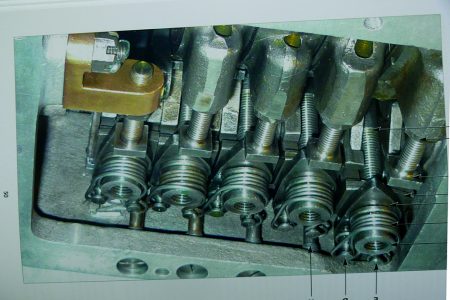

Just opening the book at random takes a chap back all those years, to that smell of warm oil, Ferodo, and stressed components. Meyer has provided commendably clear images of components in clinically clean condition, but also in the condition we are likely to encounter them, in the “British Standard Round” achieved by our predecessors and their vise grips.

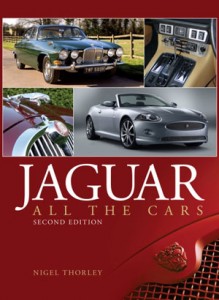

We owe the ingenious device discussed here to a Major W.G. Wilson (1874–1957), an Irishman who developed the first tank from ideas he had formulated from 1906, after early engine designs he proposed to fit to gliders as early as 1899. A 1964 patent application for an epicyclic gearbox found that Wilson had filed a similar design in 1900, and the gearbox with which he went into partnership with John Siddeley was patented in 1919. Self Changing Gears Ltd. held the design, used by, among other marques, A.C., Armstrong Siddeley, Daimler, Talbot, Lagonda, Lanchester, MG, and Riley. Those marques may have been scattered or absorbed, but the cars they built have retained a strong following; hence this book.

We owe the ingenious device discussed here to a Major W.G. Wilson (1874–1957), an Irishman who developed the first tank from ideas he had formulated from 1906, after early engine designs he proposed to fit to gliders as early as 1899. A 1964 patent application for an epicyclic gearbox found that Wilson had filed a similar design in 1900, and the gearbox with which he went into partnership with John Siddeley was patented in 1919. Self Changing Gears Ltd. held the design, used by, among other marques, A.C., Armstrong Siddeley, Daimler, Talbot, Lagonda, Lanchester, MG, and Riley. Those marques may have been scattered or absorbed, but the cars they built have retained a strong following; hence this book.

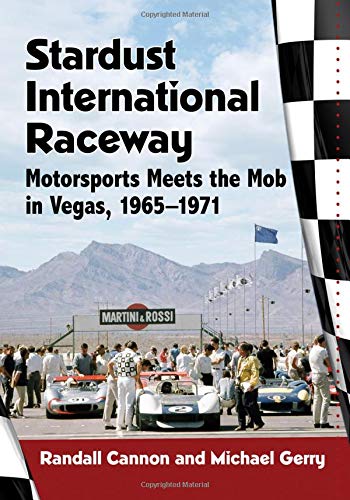

The rapid gear changing capability appealed to some prominent racing drivers such as Earl Howe, who retrofitted his Le Mans Alfa Romeo 2300, and racing manufacturers Alta, ERA, and Connaught used preselector gearboxes into the 1950s. Buses and other heavy commercial transport, tanks, trains and even modern marine designs used Wilson patents, although the American designs of automatic transmissions took a divergent path to their dominance.

How does it work? Power arrives from the engine, preferably by way of a centrifugal automatic clutch or, in Daimler’s case, by a fluid medium. The left pedal can be used as a clutch operating on the gear bands if no clutch is fitted, or by the ignorant driver if there is a clutch. Gears are selected by a hand-controlled quadrant, and that left pedal merely engages the gear when the driver is ready.

How does it work? Power arrives from the engine, preferably by way of a centrifugal automatic clutch or, in Daimler’s case, by a fluid medium. The left pedal can be used as a clutch operating on the gear bands if no clutch is fitted, or by the ignorant driver if there is a clutch. Gears are selected by a hand-controlled quadrant, and that left pedal merely engages the gear when the driver is ready.

Epicyclic gears for each gear, including reverse, are then gripped by brake bands of (now) asbestos-free lining material; top gear is direct drive, and operated by that pesky pull rod. Cleverly designed springs’ pressure provides automatic band adjustment, although provision is there for manual adjustment.

So, the driver sits smugly at the traffic lights, the engine tune enabling an idle slower than the 600 rpm when the automatic clutch engages; first gear has already been selected and engaged, and second is selected, ready for engagement when the driver, having noticed in the rearview mirror that the rest of the traffic is well astern, presses that left pedal again. It is possible to drive cars with preselector gearboxes very smoothly, with throttle pressure maintained during changes up and down. Or very jerkily; the sensitive owner should carefully assess prospective relief drivers, but there is always the full pressure of the bus bar spring ready to reward clumsy driving by bringing that left pedal right back, leaving neutrals in every gear, to be rectified by a firm left calf muscle as the owner regains command.

So, the driver sits smugly at the traffic lights, the engine tune enabling an idle slower than the 600 rpm when the automatic clutch engages; first gear has already been selected and engaged, and second is selected, ready for engagement when the driver, having noticed in the rearview mirror that the rest of the traffic is well astern, presses that left pedal again. It is possible to drive cars with preselector gearboxes very smoothly, with throttle pressure maintained during changes up and down. Or very jerkily; the sensitive owner should carefully assess prospective relief drivers, but there is always the full pressure of the bus bar spring ready to reward clumsy driving by bringing that left pedal right back, leaving neutrals in every gear, to be rectified by a firm left calf muscle as the owner regains command.

Meyer has provided clear illustrations, mostly in color, in detail down to split pins; clear instructions; Wilson’s paper to The Automobile Engineer in 1932; relevant diagrams; part numbers; specialist help addresses; even gasket patterns.

Owners of Armstrong Siddeleys and all those other marques that fitted these gearboxes need this book, even if only to encourage the tame mechanic engaged in the maintenance of cars so equipped, and it is just as useful as an aid to nostalgia for those of us who have moved beyond ownership.

Copyright 2021 Tom King (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

How do I buy a copy of this book? Through the Australian Armstrong Siddeley Club or?

Tom King is a first class reviewer!