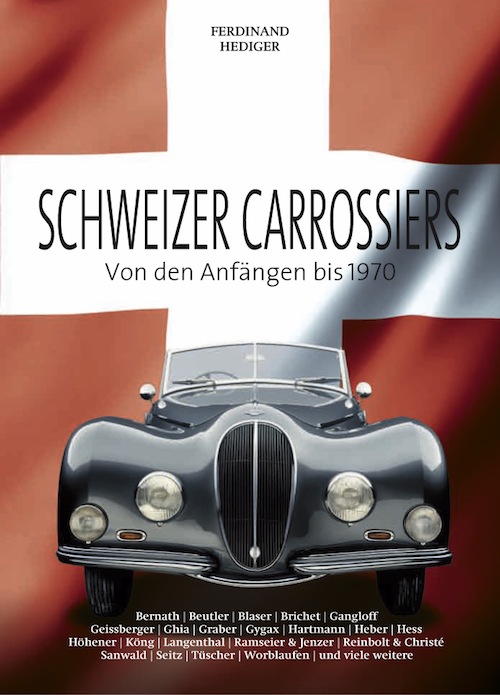

Schweizer Carrossiers – Von den Anfängen bis 1970

(German) Beutler Porsches, Gangloff Bugattis, Graber Bentleys—some very recognizable names . . . Swiss names.

Even if you don’t speak German—in which case you may not know that the the title of the book means Swiss Coachbuilders, From the Beginning to 1970—you’ll enjoy this fine, oversize and well-presented offering, not least because of pro photographer Michel Zumbrunn’s excellent work. Add the book’s limited edition and absurdly low price and you have a winner.

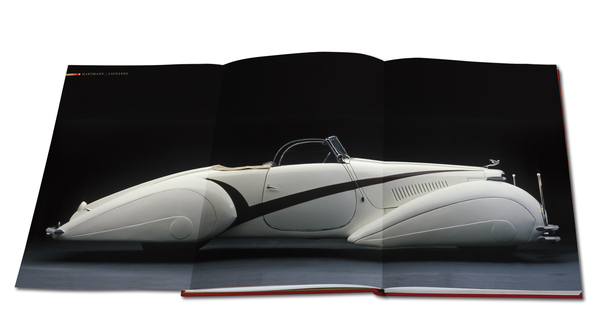

Do you think of the Swiss as flashy, flamboyant, loud, over the top? Probably not. Nor is the coachwork their carrosiers erected on chassis ranging from the lowliest of town and micro cars to the most high-brow of marques. There are, of course, exceptions. Today you’d have to look no further than Franco Sbarro whose firm has since 1971 produced decidedly wild replica and sports cars and any number of design and engineering exercises for a variety of consumer goods. In the olden days, something like the very French-looking super-swoopy 1937 V-16 Cadillac bodied by Hartmann was the exception and not the rule (see bottom photo).

While the author’s introductory essay points out right away the geographic proximity to France and that country’s pioneering role in championing and developing the automobile as the reason for a distinct French influence on Swiss ocachbuilding, the Swiss by and large think of their coachwork as “conservative” in terms of shapes, colors, and frivolous embellishments.

While the author’s introductory essay points out right away the geographic proximity to France and that country’s pioneering role in championing and developing the automobile as the reason for a distinct French influence on Swiss ocachbuilding, the Swiss by and large think of their coachwork as “conservative” in terms of shapes, colors, and frivolous embellishments.

Bespoke coachwork, here and most everywhere else, was on its way out after WWII and so this book focuses on inter- and prewar examples. High fashion may not have been a prominent feature but high quality most certainly is, an attribute one definitely associates with anything bearing a “Swiss made” label.

The book presents 21 of the “better known” Swiss firms and an additional 31 “minor” builders, the latter condensed to a mere 14 pages at the end with entries as short as a single paragraph. This is intentional because the book presents itself as merely a long-overdue introduction to the topic, and a mainly pictorial one at that (no production specs/details, tables, charts, lists etc.). Also, only passenger cars are considered but no commercial/utility bodies of which quite a number were made in Switzerland.

Just looking at the photos impresses upon the reader something the text does not address: a disproportionately large number of open cars. Why a country more known for snow and skiing than a temperate climate should have such a preference for open coachwork remains unexplained. It may, perhaps, simply reflect the tastes of an international clientele that had their cars bodied there but then used them elsewhere.

If you have already been following Swiss coachbuilding you may recognize the author’s name as a frequent contributor to the bi-monthly oldtimer magazine SwissClassics (and author of half a dozen automobile books). These articles form the basis of this book. The magazine’s archives as well as that of the very important—and very low-key—Swiss Car Register have yielded many of the period illustrations included here. While the book contains a large quantity of these, some of them are painfully small—these two aspects obviously being directly related to one another. On the other hand, at least a dozen of the Michel Zumbrunn modern photos used as chapter openers are lager than what you’d normally see: tryptichs (which do take some fiddling to fold back together without bending the third panel) that are about 27 inches wide.

The publication of the book coincided with the exhibition “The Swiss Coachbuilders” at the Pantheon in Basel (Oct. 2013–April 2014) which has published its own catalog of the exhibition.

Considering the top-notch photo reproduction, paper and binding, and the extra production costs for the large photo panels, this book represents an uncommonly good value.

Copyright 2014, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter