Warhol and Cars, American Icons

There are houses in Montclair, New Jersey, sitting a few blocks up the hill from the Montclair Art Museum, where one can view the New York City skyline. It wouldn’t be far wrong, then, to say that this small institution is in the shadow of the great city, both literally and figuratively, but this does not mean that MAM is not worth a visit. Certainly the collection is not going to rival those of The Met, MoMa, or the Guggenheim, but MAM has gathered a strong collection of 18th and 19th century American masters, Copley, Stuart, Sargent, Cole and Whistler—including Hopper’s 1929 Coast Guard Station. In 1998, the museum acquired Warhol’s Twelve Cadillacs and this became, according to director Lora Urbanelli, “the cornerstone and catalyst for MAM’s growing commitment to modern and contemporary art.” With assistance and donations from private collectors and especially Pittsburgh’s The Andy Warhol Museum, in 2011, MAM displayed Twelve Cadillacs in a Warhol show built around his automobiles; this book was published as a companion to and in conjunction with this exhibition.

Stavitsky, MAM’s chief curator, tenders an informative essay about Warhol, and one of her main ideas is that years before his silkscreened canvases of automotive fatalities, began in 1963, Warhol had already used automobiles in his work, but this fact had been largely unrealized for many Warhol fans and scholars. Perhaps you have seen one of the death canvases: a photo of an overturned 1956 Ford Customline (Stavitsky has gone to some trouble to accurately identify the various models presented in the book) with the injured occupants stretched out of the crushed rear and side windows is silkscreened either singularly or in groups against a red, yellow or green monochromatic canvas. Warhol believes that “when you see a gruesome image over and over again, it really doesn’t have any effect” and “the more you look at the same exact thing, the more the meaning goes away.” Think of the numbing effect of the grossly repetitive disaster footage, a tornado, a fire, a tsunami, a shooting, that television news incessantly exploits as viewers become numb in the wake of such repetition. Warhol scores a point.

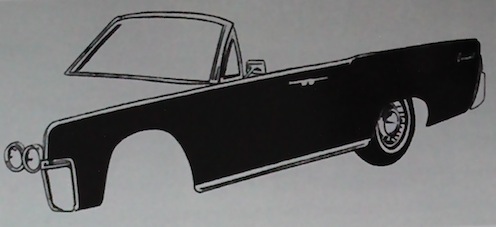

The pre-disaster automobile renderings come not that far ahead of the death pictures, excepting the sketches Andy did of his brother’s fruit and vegetable truck back in the late 1940s, but this is a stretch on Stavitsky’s part. The true automotive theme came alive in 1958 when Warhol was still accepting advertising assignments, and these bear a lightness and frailty that belie what happens not that much later in his career; life moves swiftly in an era of quickly changing attitudes and sensibilities. Warhol and Cars reproduces two samples of these car illustrations, both done on Strathmore paper, a frilly mannequin standing before a sleek 1959 Sports Fury Convertible and a silhouette of a 1958 Cadillac Coupe de Ville. Although the cars are stylized, they are accurate, and, like Warhol’s early commercial shoe illustrations, they show a side of the artist glossed over or even ignored in much of the critical literature: Warhol’s diamond-hard strength in draughtsmanship. Soon after, vying for recognition simultaneously in the arts both commercial and fine, comes the November 1962 edition of Vanity Fair that features reproductions of Warhol’s cars, some precisely drawn and painted on canvas, some silkscreened on canvas, among them a startling yet stately image, acrylic with silver paint and pencil, of a 1962 Lincoln Continental:

The pre-disaster automobile renderings come not that far ahead of the death pictures, excepting the sketches Andy did of his brother’s fruit and vegetable truck back in the late 1940s, but this is a stretch on Stavitsky’s part. The true automotive theme came alive in 1958 when Warhol was still accepting advertising assignments, and these bear a lightness and frailty that belie what happens not that much later in his career; life moves swiftly in an era of quickly changing attitudes and sensibilities. Warhol and Cars reproduces two samples of these car illustrations, both done on Strathmore paper, a frilly mannequin standing before a sleek 1959 Sports Fury Convertible and a silhouette of a 1958 Cadillac Coupe de Ville. Although the cars are stylized, they are accurate, and, like Warhol’s early commercial shoe illustrations, they show a side of the artist glossed over or even ignored in much of the critical literature: Warhol’s diamond-hard strength in draughtsmanship. Soon after, vying for recognition simultaneously in the arts both commercial and fine, comes the November 1962 edition of Vanity Fair that features reproductions of Warhol’s cars, some precisely drawn and painted on canvas, some silkscreened on canvas, among them a startling yet stately image, acrylic with silver paint and pencil, of a 1962 Lincoln Continental:  stately because of the terse lines of this understated car, captured easily by Warhol, and startling because of how Warhol conceives this image. He strips it down to curbside essentials, a three-quarter front view, from above, of the body shell, only the near rear wheel pictured, and the viewer is gently led into filling in the absent hood and inner fender well by way of connective imagination. Warhol’s attention then abruptly turns to his films, interviews and literature, his renown growing apace, and it isn’t until 1985 that he turns back again to the automobile, this time doing pop art renditions of the famous Doyle, Dane, Bernbach Volkswagen Beetle ads, along with similarly rendered pieces done on commission for a German collector. Although harsh to say it, MAM and Stavitsky become lucky in the sense that Warhol dies while in the midst of a major automotive exercise, a commission from Daimler-Benz—the timing could not have been better, the book not wrapped up so tidily.

stately because of the terse lines of this understated car, captured easily by Warhol, and startling because of how Warhol conceives this image. He strips it down to curbside essentials, a three-quarter front view, from above, of the body shell, only the near rear wheel pictured, and the viewer is gently led into filling in the absent hood and inner fender well by way of connective imagination. Warhol’s attention then abruptly turns to his films, interviews and literature, his renown growing apace, and it isn’t until 1985 that he turns back again to the automobile, this time doing pop art renditions of the famous Doyle, Dane, Bernbach Volkswagen Beetle ads, along with similarly rendered pieces done on commission for a German collector. Although harsh to say it, MAM and Stavitsky become lucky in the sense that Warhol dies while in the midst of a major automotive exercise, a commission from Daimler-Benz—the timing could not have been better, the book not wrapped up so tidily.

The book is attractive. Pages are crisp and glossy, uncluttered, with dark, large font, double-spaced, and the illustrations, many in color, have room to breathe. The inclusion of original artwork from car brochures, to show Warhol’s referencing, adds to the overall quality. Bits of Warhol’s wisdom and explication are strewn throughout, and the book has sufficient notes to further explore various ideas and/or offer source material and citations. (It is of interest to note that many citations are from emails from various scholars and curators, a trend entrenched by 2011, the publication date.) There is an exhibition checklist, and one wishes Warhol Cars were a complete illustrated catalog, and one is disappointed that, in the illustrative figures throughout, the size of each is not listed; and, too, there is some confusion as to the sequencing of these images. Stavitsky’s prose is clear, direct, and does not rely on abstruse theoretical jargon, to the point where one would actually welcome a more incisive academic approach. The book’s title is quirky; it is more than okay to honor Warhol as an American icon, but to so designate “and Cars” becomes problematic. There are many iconic cars, and many iconic American cars, but “cars” cannot be considered as American icons; one would guess that more thought would have been given to the title for the exhibition and the book. But these are minor complaints. There should be a fair audience for Warhol and Cars—there must be more than a few out there who have various interests, allowing room, among many things, for the automobile and the fine art canvas; and especially considering Warhol’s ideas of art as business and business as art, this pair complements one to the other.

The book is attractive. Pages are crisp and glossy, uncluttered, with dark, large font, double-spaced, and the illustrations, many in color, have room to breathe. The inclusion of original artwork from car brochures, to show Warhol’s referencing, adds to the overall quality. Bits of Warhol’s wisdom and explication are strewn throughout, and the book has sufficient notes to further explore various ideas and/or offer source material and citations. (It is of interest to note that many citations are from emails from various scholars and curators, a trend entrenched by 2011, the publication date.) There is an exhibition checklist, and one wishes Warhol Cars were a complete illustrated catalog, and one is disappointed that, in the illustrative figures throughout, the size of each is not listed; and, too, there is some confusion as to the sequencing of these images. Stavitsky’s prose is clear, direct, and does not rely on abstruse theoretical jargon, to the point where one would actually welcome a more incisive academic approach. The book’s title is quirky; it is more than okay to honor Warhol as an American icon, but to so designate “and Cars” becomes problematic. There are many iconic cars, and many iconic American cars, but “cars” cannot be considered as American icons; one would guess that more thought would have been given to the title for the exhibition and the book. But these are minor complaints. There should be a fair audience for Warhol and Cars—there must be more than a few out there who have various interests, allowing room, among many things, for the automobile and the fine art canvas; and especially considering Warhol’s ideas of art as business and business as art, this pair complements one to the other.

Copyright 2013, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter