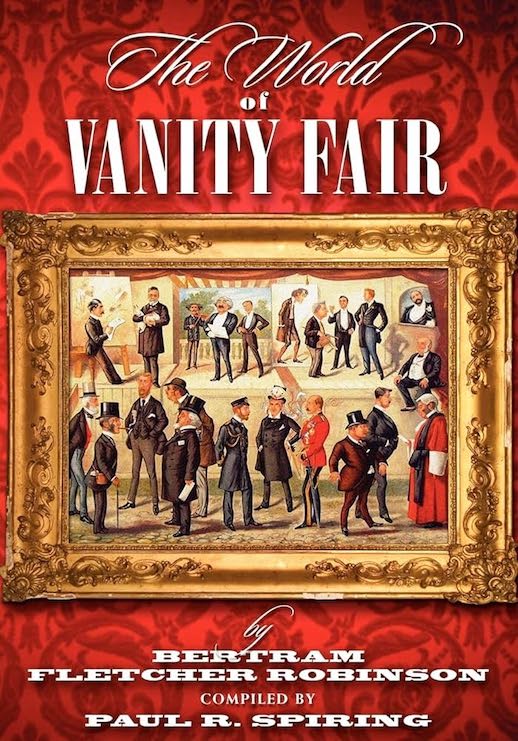

The World of Vanity Fair

by Paul R. Spiring

by Paul R. Spiring

“Our portrait of Parnell is a very good one. ‘He was not a heaven-born orator,’ said Jehu Junior, ‘but an unbounded belief in himself has carried him on; he has it in his hands to do much for his country either for good or evil.’”

If you want to get an idea of what people were about at the dawn of automobility, a British weekly chronicle of Victorian life is a good place to start: Vanity Fair magazine (“A Weekly Show of Political, Social and Literary Wares”) published from 1868 to 1914. It was to the British what, 30 years later and with a greater focus on politics, The Saturday Evening Post (not to be confused with several British newspapers of that name) was to Americans. Both were known for commissioning lavish illustrations and original works of fiction and are today best remembered for the former.

Founded by Thomas Gibson Bowles, Vanity Fair covered current events and, from fashion to scandals, the cultural stirrings of its day. It also parodied its vanities, and what better way to do this than with caricatures and cartoons (some are exaggerated spoofs, others quite realistic portraiture), accompanied by entertaining commentary and background. This was often wholly sympathetic but when called for could be sharp although not malicious. “Any press is better than no press” was as true then as it is now. Bowles, it should be noted, did not just jeer from the sidelines. He sold the magazine in 1889 and went into politics as an MP.

The man who led Vanity Fair as editor for 126 issues during the period under consideration here, 1904–06, had started as a contributor to it. Bertram “Bobbles” Fletcher Robinson had joined the bar in 1896 but never practiced law, making a name for himself as a sportsman, journalist, and author. His published pieces since 1893 number nearly 300, including detective stories, wherein lies the foundation for his connection to Sherlock Holmes’ literary father, Arthur Conan Doyle. The extent of that influence or even collaboration has been debated ever since, some contemporaries going so far as to accuse Conan Doyle of having plagiarized Bobbles’ material and then murdered him—he had died young (36) and quite sudden—to cover it up, which almost resulted in the exhumation of his body! This book’s author has examined the topic in several books and argues that Conan Doyle’s success is “partly attributable” to Robinson whom, it has now been established, he paid £550 [ca. £45.000 today] for his material.

The man who led Vanity Fair as editor for 126 issues during the period under consideration here, 1904–06, had started as a contributor to it. Bertram “Bobbles” Fletcher Robinson had joined the bar in 1896 but never practiced law, making a name for himself as a sportsman, journalist, and author. His published pieces since 1893 number nearly 300, including detective stories, wherein lies the foundation for his connection to Sherlock Holmes’ literary father, Arthur Conan Doyle. The extent of that influence or even collaboration has been debated ever since, some contemporaries going so far as to accuse Conan Doyle of having plagiarized Bobbles’ material and then murdered him—he had died young (36) and quite sudden—to cover it up, which almost resulted in the exhumation of his body! This book’s author has examined the topic in several books and argues that Conan Doyle’s success is “partly attributable” to Robinson whom, it has now been established, he paid £550 [ca. £45.000 today] for his material.

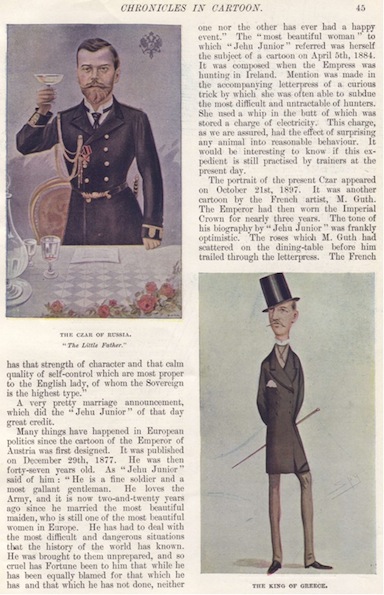

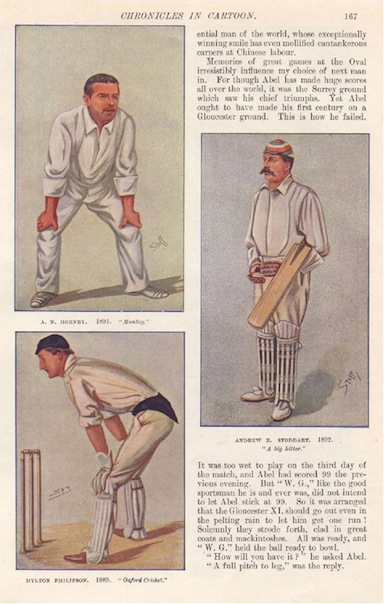

This book reproduces, as color facsimiles, the 15 articles Robinson produced for another periodical while at Vanity Fair, The Windsor Magazine. Entitled “Chronicles in Cartoon” they feature 394 of the 1960 caricatures by various artists that had appeared in Vanity Fair by then, with narrative specifically written by, presumably, Robinson. This material is, in fact, what author Spiring believes Robinson was preparing to publish himself (plus another five articles referred to in his notes) as his magnum opus, had his early death not kept him from it. The illustrations and their commentary that once had run in Vanity Fair individually over the years are here grouped into professions/walks of life and the text relates specifics as to the people shown and the artists that drew them, elaborating on the original captions and dispensing occasional tidbits of the o tempora! o mores! variety. By the time Robinson wrote this, some of the material was already more than 30 years old so there was plenty to comment on.

This book reproduces, as color facsimiles, the 15 articles Robinson produced for another periodical while at Vanity Fair, The Windsor Magazine. Entitled “Chronicles in Cartoon” they feature 394 of the 1960 caricatures by various artists that had appeared in Vanity Fair by then, with narrative specifically written by, presumably, Robinson. This material is, in fact, what author Spiring believes Robinson was preparing to publish himself (plus another five articles referred to in his notes) as his magnum opus, had his early death not kept him from it. The illustrations and their commentary that once had run in Vanity Fair individually over the years are here grouped into professions/walks of life and the text relates specifics as to the people shown and the artists that drew them, elaborating on the original captions and dispensing occasional tidbits of the o tempora! o mores! variety. By the time Robinson wrote this, some of the material was already more than 30 years old so there was plenty to comment on.

However selective, the book is a Who’s Who of its time. Men of state, of war, of the cloth, of sports, the sciences—the luminaries of their day may well be unknowns to us moderns. If nothing else, the book demonstrates that fame, and infamy, are fleeting. Interestingly, even though The Windsor Magazine billed itself as “An Illustrated Monthly for Men and Women,” no women are considered deserving of inclusion; the only four covered are Royals.

Robinson referred to some of the illustrations by titles other than those used in Vanity Fair (not out of fiat but because subjects’ position/status may have changed over the years). The Index, which lists every drawing, therefore states both Robinson’s title and the original Vanity Fair publication date. The listing is in alpha order of subject’s first or last name, or official title. This is rather unsatisfactory; example: French composer Gounod is listed under “G” without a first name (Charles, which should have put him under “C”); he is followed by “Henry Fawcett” and “Herbert Spencer” which are followed by “Her Majesty Queen Alexandra.” Try finding anybody this way! Illustrators are identified if they are known.

The publisher explains the high price as a consequence of it being a print on demand product and color books being expensive to produce this way. A lower-cost b/w edition is being contemplated.

You could bury yourself in reams of dry textbooks about the Victorians, or meet them here, up close and personal. Slightly exaggerated perhaps but no less relatable.

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter