French Curves: Delahaye, Delage, Talbot-Lago

by Adatto, Figoni, Hinds; photos by Furman

by Adatto, Figoni, Hinds; photos by Furman

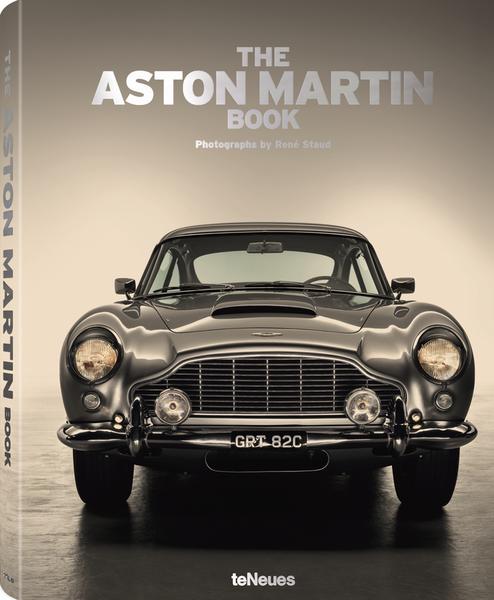

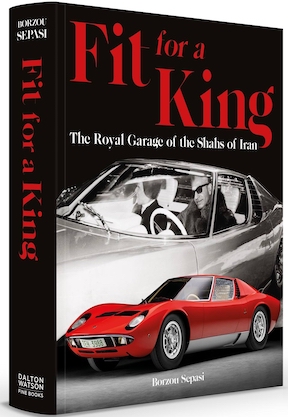

Curves . . . roll that image around in your noggin for a moment. If cozying up to a new book can be turned into an occasion, this is the sort of book you’ll want to be your companion. Elegant, well turned out, beautiful to behold—and you’ll still respect it in the morning.

Enough already. Principal writer/French car expert Richard Adatto and photographer-publisher Michael Furman have teamed up once more and here present volume two of an intended three bringing the treasures of the Mullin collection to the world, especially to those poor souls who have not yet made the pilgrimage to exotic Oxnard, California. It is in fact pretty much Mullin’s shrine to all things French Art Deco that makes “The ‘Nard”—better known as an agricultural center for strawberries and lima beans—exotic.

This book focuses on three marques: Delahaye, Delage, Talbot-Lago. As its predecessor, this volume was launched at the Pebble Beach Concours (the publisher has a booth right by the entrance to the field), practically Mullins’ home away from home. He has displayed his cars here for 27 years and, in fact, won that very year for the very first time—for a marque that will be covered in a future book, a 1934 Voisin C-25 Aerodyne. He described that award as “the most special, significant, rewarding thing that’s ever happened to me [on the automotive front],” although receiving only the year before a Lifetime Achievement award for his many years of dedication to the Bugatti surely caused champagne corks to fly too. What all this means is that the Mullins are serious about French Art Deco—not just automobiles—and discriminating, astute collectors.

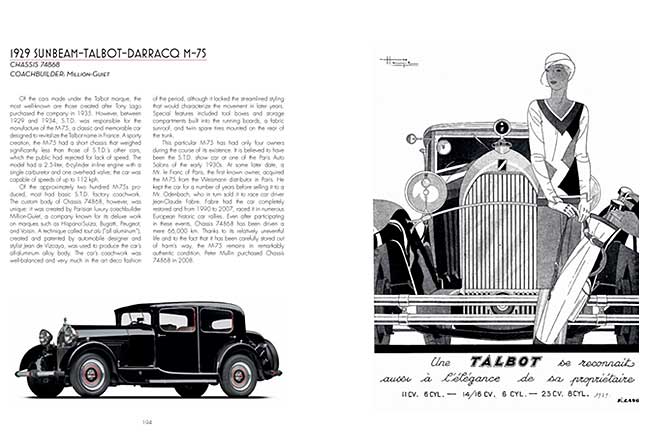

The cover photo, and your assumptions, notwithstanding, this book does not just present sexy, swoopy eye candy, cars with lines of such fluidity that one wonders how they could have been formed of inert material, but also boxy cars with undramatic tourer or staid formal bodies. The purpose of this exercise is to illustrate the evolution of a style of coachwork that has a distinctive idiom. If you expect enlightenment from this book as to just what that is, brace yourself: the collective wisdom, according to ex-Bonhams auction specialist and now Mullin’s chief curator Andrew Reilly is, “you’ll know it when you see it.” Harumph.

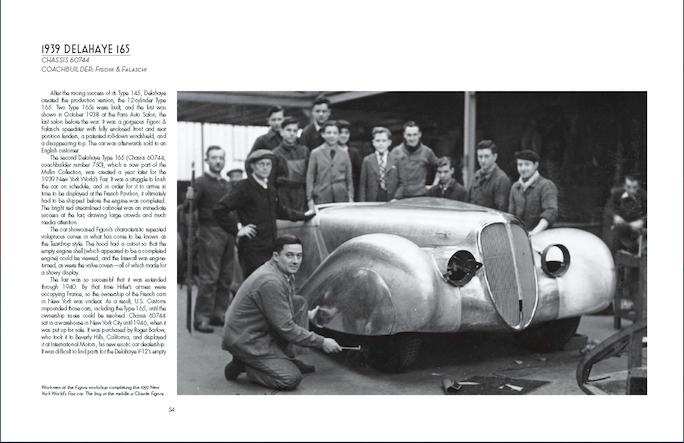

Even the Foreword by coachbuilder Joseph Figoni’s son Claude is noncommittal, explaining only that Figoni took inspiration from “everything from birds and fish to flowers and women” and otherwise staying on firmer ground by discussing his methods and professional activities. The reason Figoni (1894–1978) alone of all the various designers/coachbuilders whose work is gathered here is singled out in this manner is that he is easily France’s most innovative stylist of his era. Five of the 25 cars in this book are by his hand, besting Chapron by one.

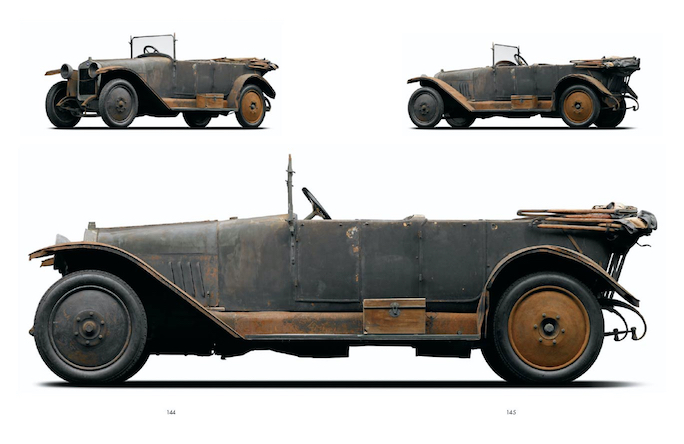

Divided by marque, each with its own introductory text, the models range from 1918 to 1951 and include road and race cars. The individual car descriptions briefly cover basic features of the model and its place in the larger scheme of things, and then go into the specific car in the collection in detail in terms of ownership and restoration history. Not all the cars shown here are, in fact, restored and therein is revealed an important aspect of Mullin’s philosophy about being a custodian of vintage cars.

Divided by marque, each with its own introductory text, the models range from 1918 to 1951 and include road and race cars. The individual car descriptions briefly cover basic features of the model and its place in the larger scheme of things, and then go into the specific car in the collection in detail in terms of ownership and restoration history. Not all the cars shown here are, in fact, restored and therein is revealed an important aspect of Mullin’s philosophy about being a custodian of vintage cars.

Photos. At last we came to the heart of the matter. Any book with Michael Furman’s name as the photographer is automatically an elevated affair. Furthermore, books that he publishes himself, as is the case here, have top-shelf production values in regards to paper, photo manipulation, printing, and binding. The many period photos included here have probably never looked so good before and one wonders what technical skills he and his staff possess that others don’t or don’t care to employ. Production cost is obviously always a factor for everyone but Furman and his staff and vendors show how high the bar can be, ought to be, raised—and all without resorting to doing the work in low-labor countries.

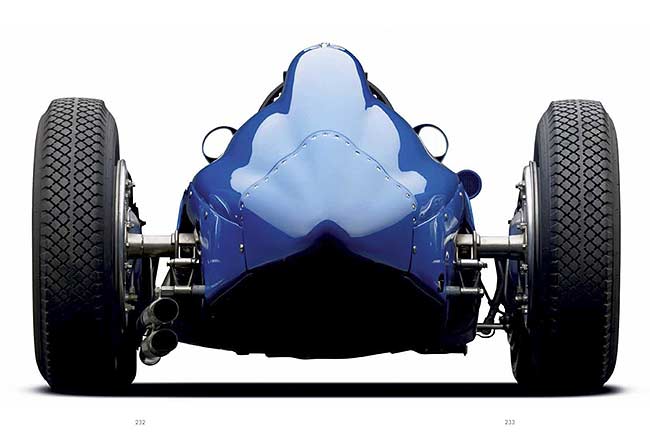

All the set-up studio photography is done with exaction attention to lighting and contrast. Except for the chapter openers, all exterior shots are silhouetted and printed on white background so as to let the lines of the cars speak without distraction. Technically, the full-frontal shots are the most remarkable because even when printed on flat paper, the way light and shadow are used conveys a distinct sense of dimensionality. Even without 3D glasses, what is round in real life looks round on paper. Textures too are captured with utter realism. Leather grain, tire treads, spark plug wires, cast iron next to gleaming chrome next to satiny brass, bottomless paint—all true to life. Looks easy. Is not.

All the set-up studio photography is done with exaction attention to lighting and contrast. Except for the chapter openers, all exterior shots are silhouetted and printed on white background so as to let the lines of the cars speak without distraction. Technically, the full-frontal shots are the most remarkable because even when printed on flat paper, the way light and shadow are used conveys a distinct sense of dimensionality. Even without 3D glasses, what is round in real life looks round on paper. Textures too are captured with utter realism. Leather grain, tire treads, spark plug wires, cast iron next to gleaming chrome next to satiny brass, bottomless paint—all true to life. Looks easy. Is not.

Even some of the historical visuals—maker/coachbuilder documents, vintage photos—are new to the record. Old hands will perk up at the chapter “L’Affair Geo Ham.” It paints a rather acrimonious picture of the relationship with the French illustrator whom the literature generally records as having provided valuable, and appreciated, styling advice. Judging by the material from the Figoni & Falaschi archives (which Claude F. administers) this can apparently no longer remain an accurate view.

Bibliography. No Index.

Copyright 2012, Charly Baumann/Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter