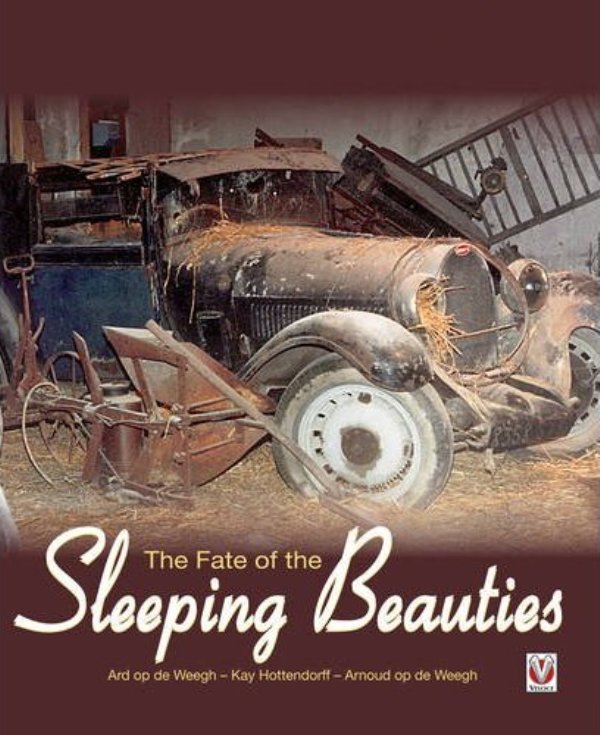

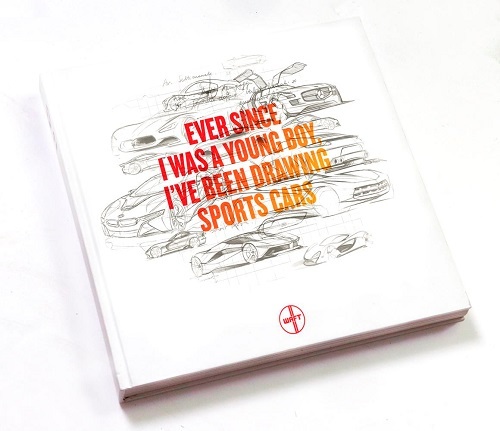

The Fate of the Sleeping Beauties

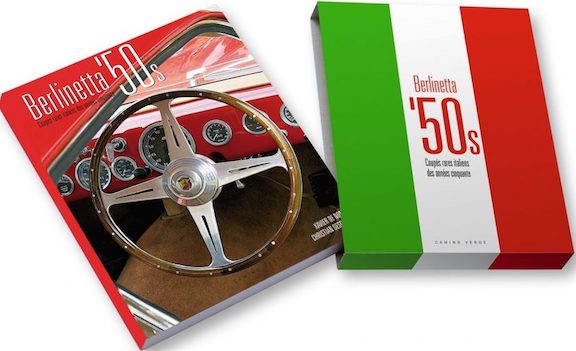

by Ard op de Weegh, Kay Hottendorff & Arnoud op de Weegh

by Ard op de Weegh, Kay Hottendorff & Arnoud op de Weegh

“It is a pity that such a distorted picture of Michel Dovaz has prevailed for so many years. This remarkable Frenchman deserves better. His dream should not have been destroyed. It was taken from him, even though he had done nothing to deserve it.”

This is one book that could have used a subtitle! Not only are there several others with the words “sleeping beauties” in their title, one of them covers the exact same subject—except . . . it tells a vastly different story and its sins of omission and commission are the raison d’être for this new one.

Unlike the “sleeping beauties” books that cover generic old, abandoned, or barn find cars, this book deals with a specific collection, that of Frenchman Michel Dovaz. It had never had that name, or any name, but was given that moniker by the popular press when it was first made public in the mid 1980s when German photographer Herbert W Hesselmann published photos he had taken in 1983 in several magazines and later in a book (Sleeping Beauties, with Halwart Schrader, ISBN-13: 978-3283005498, 1986 and expanded in 2007). This is not the place to retell that story but a few remarks are necessary so as to grasp the purpose of the new book which is best described as a “forensic effort” both in regards to the contents of the collection and the background of its owner. And while it does advance the body of knowledge, the authors either were too polite or too unimaginative to probe very deeply into the motives of the principals on either side of the story. (Woodward and Bernstein investigating Deep Throat this is not!)

The key factor that would ultimately cause the disbanding of the Dovaz collection was his condition of anonymity for allowing Hesselmann to photograph the several dozen cars—from blueblood classics to lesser fare—he had bought over the decades, driven hard and put away wet when they broke down and parts became hard to find. Not wanting to repair or part with them, he stuffed them into barns and let nature take its course. And that is what made the press, at that time, condemn him as a stubborn eccentric who ruined priceless cultural artifacts. Worse, one magazine writer named names, which led to theft and vandalism and forced the removal of the collection to a different location that also could not be kept secret. And while Hesselmann insists his hands are clean he also did not speak up for his source, Dovaz. The new authors leave this matter unexplored and don’t even investigate why Hesselmann/Schrader did not correct in the revision of their book more than 20 years later the record they themselves had contributed to muddying. (The reprint still uses the pseudonym “Pierre” for Dovaz, as if all the world by then didn’t know who he was.) Nor do the authors probe why the intensely private Dovaz ever sought or permitted such publicity in the first place, and Dorvaz, who wrote the Foreword, is allowed to skirt the issue. Marks for investigative journalism: F.

But, one good thing came of the Hesselmann book: Kay Hottendorff (an engineer) got a supersized poster of a photo from that book as a birthday present. It piqued his curiosity and lead to thousands of hours of research which, one day in an Internet forum, brought him to the attention of Dutchman Arnoud op de Weegh (a university student) who with his father Ard (a school principal) were on the same trail. A meeting in person resulted in the joining of forces, et voilà, a book is born.

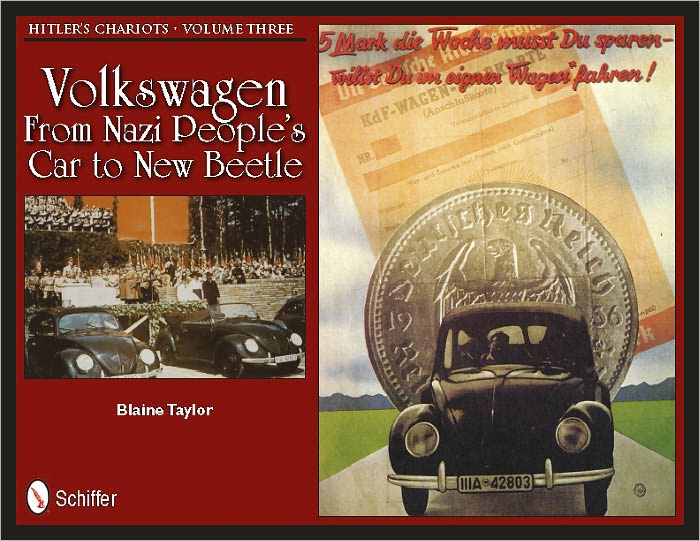

The book opens with a 30-page treatment of some of the above. Dovaz’s collection encompassed several marques but since Bugattis were its crown jewels, a brief overview of Bugatti history and lore precedes the book’s description of the 21 Bugs Dovaz is known to have owned or still owns. In all 55 of his possibly 70 cars are covered. They are presented by marque and within that by year; the Table of Contents lists each by type/model (the Index does not). While the descriptions are specific to the particular Dovaz car (in terms of ownership and, if applicable, restoration history etc.) there is also basic commentary about the overall model run. For the “important” cars the coverage is fairly deep, lesser cars (cf. 2CV, VW K70 etc.) barely warrant a page each and in some cases don’t even show the Dovaz car but a stock photo. The bulk of the photos show the cars during or after the 1984 move of the collection, in subsequent storage facilities, in museum displays, and during restoration. A good number of the cars have been restored in recent years by new owners and even Dovaz, motivated by a richly priced auction market, has had some restored. In a collecting climate that only recently has made peace with and even recognized the intrinsic historic value unique to unrestored cars, the time-capsule aspect of the Dovaz cars is only now given its due. He is now in his eighties—and probably wishes he had kept the story of his cars to himself for another 20 years! His commentary about the 1950s—when, he says, the problem was not buying the cars but getting rid of them—where a young man of 20 years and moderate means could buy himself a used Bugatti every few months when he was tired of the previous one will make today’s reader think of opportunities that will never come again.

The op de Weeghs have made classic cars their vocation and have launched a web project about stolen classics and are working on a revisionist history exonerating the Schlumpf brothers and a book about car graveyards in Europe.

Since we do comment on these matters, it must be said, reluctantly and with apologies to the authors, that the proofreading is abysmal and the English translation inelegant. The book first appeared in Dutch and there will be German and French versions.

Copyright 2011, Charly Baumannn/Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter