Building Dutch Air Power in World War II

The Role of Lend-Lease and Aircrew Training in the United States

by Nicholas Michael Sambatuk

by Nicholas Michael Sambatuk

Nearly the first 100 pages, comprised of introduction and four chapters, provide the historical perspective leading up to the fifth chapter’s opening as “two trains pull into Jackson’s [Mississippi] downtown station and the motley throng emerged onto the platform late on the night of Friday 8 May” 1942.

That “throng” of 484 had traveled by ship then train from Melbourne, Australia to Jackson. But really they had originated as each had escaped from the already badly war torn Dutch East Indies—some with little more than the clothes they wore.

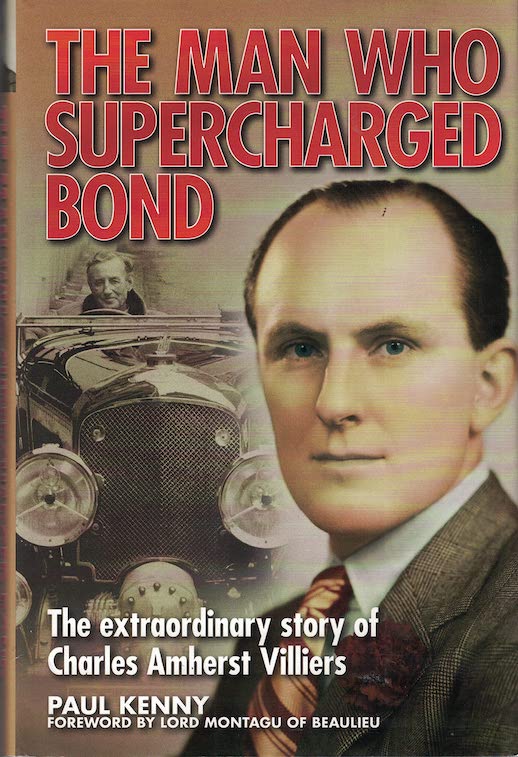

Not only are their “uniforms” less than uniform but look at the short pants. Where they came from was in the tropics. Where they arrived, spring was just arriving. Jackson, Mississippi citizens quickly stepped up helping the new residents with warmer clothing although it did take a bit longer for respective governments to also issue more appropriate uniforms as shown in bottom image on the book’s cover.

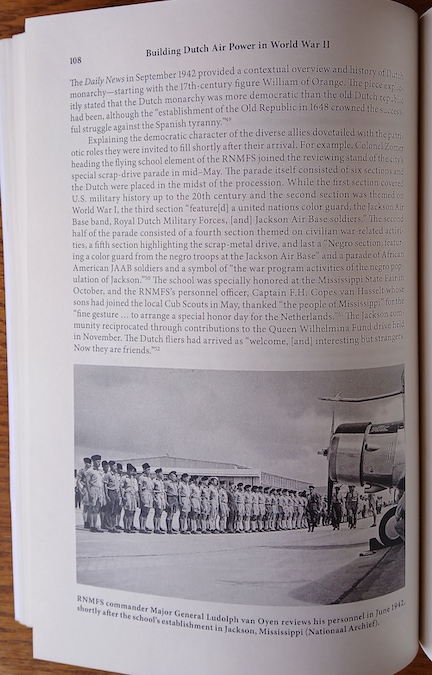

Members of the group identified themselves as Dutch yet, ethnically speaking, they were more diverse. While some were Dutch-born from the Netherlands, also included were “four German nationals, two Chinese, two Malays, two Belgians, two from Netherlands West Indies, a Canadian and a South African.” Most were male though 57 minor children and sixty women were part of the contingent too. All had been uprooted by war and transplanted to form the core, the beginnings, of a US-based training school being established to “train and organize a small [Dutch] Air Force.”

Before going further, it’s important to note the importance of those first four chapters for what they share is an aspect of World War II history not generally or usually made clear to students in either high school or university history classes. That it can be and is told here once again points up the importance of chapter end notes and a bibliography.

Essentially, in those earliest pages, author Nicholas Michael Sambatuk explains how a neutral country, The Netherlands, became—forcibly—drawn into the war by the May 1940 Nazi invasion and subsequent occupation of their country. Too, there’s another relevant fact: this neutral country had been an empire builder: creating the West Indies (Surinam, Curacao, Aruba) in the Americas and the archipelago that today is Indonesia but known then as either the NEI or DEI, Netherlands East Indies or Dutch East Indies. Once the homeland and then the DEI were occupied by Nazis and Japanese respectively, the Dutch were neutral no longer.

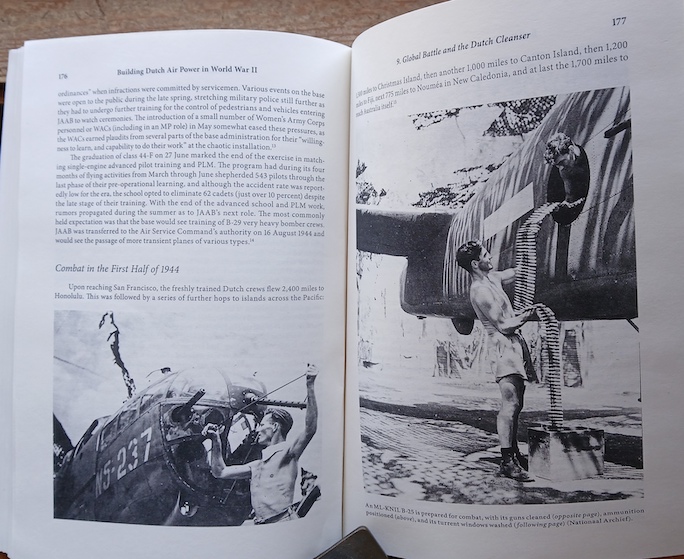

Training successfully completed, the men got their wish to return to do battle in the West Indies and find loved ones they’d been forced to leave behind. From what you see you have an indication of the local climate.

What had been behind Japan reaching ever outward to DEI and even Hawaii had been its need for their resources, per this: “Japan’s strategists were acutely aware of their need for oil and the paucity of domestic supply, and they recognized that NEI’s output more than equaled their expected demand . . . [so] Japan was determined to invade NEI.” At this point it remained unstated yet a real threat that other lands, including Hawaii or Australia, could be next.

Chapters follow describing the establishment and operation of the training school and also how well the Mississippians and Dutch got along with one another, forming what would turn out to be numerous lifelong friendships including marriages. Still, the concluding pages seemed incongruously titled “Fruits of War” for we tend to think of fruit as something sweet and good-for-us, attributes not associated with the death and destruction of war.

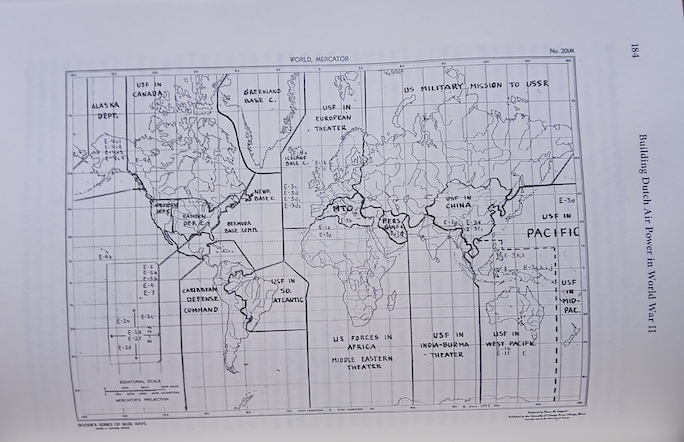

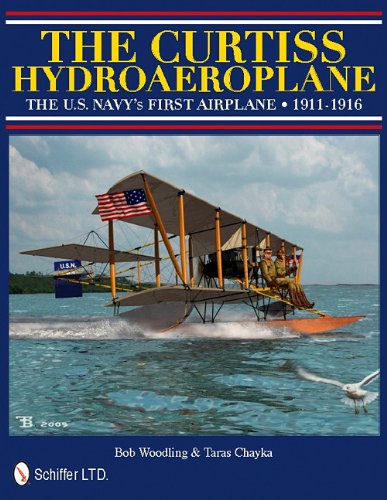

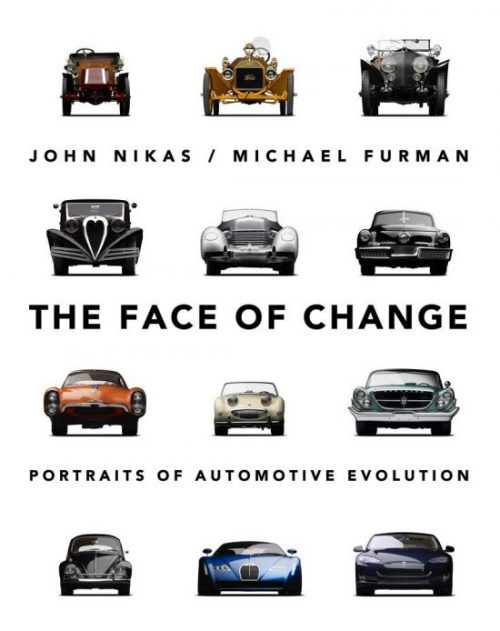

This mercator map dated 6 July 1945 is marked to indicate the delineations of the Allied theaters globally.

That said, author Sambatuk exonerated his choice of a title with this leavening observation: “Wars reshape the fates of countries, and while doing so they also massively impact the lives of myriad people. Obviously, these impacts are often characterized by tragedy, since death, destruction, and dislocation are endemic to wars. Other impacts carry implications that are more positive. . . . If not for the arrival [in Jackson, Mississippi] of the Netherlanders’ forced relocation, the children of Jackson would likely never have learned how differently Christmas traditions are observed elsewhere. . . . The children born of U.S.-Dutch unions would not have existed, nor would the lives that they touched have been quite the same without the RNMFS* arriving and functioning as it did. . . . At a personal level, world changing events matter in surprising and lasting ways.”

Those concluding words nicely sum up the story the book tells enabled by the historiographies, theses and studies published along with and interviews conducted since in Mississippi and Indonesia from which Air War College scholar Nicholas Michael Sambaluk drew to assimilate this presentation. Bearing witness to the depth and breadth of resources he accessed are the just shy of 30 pages of chapter notes and bibliography as well as the archives and individuals he acknowledges in his Preface.

*RNMFS Royal Netherlands Military Flying School

Copyright 2025 Helen V Hutchings, SAH (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter