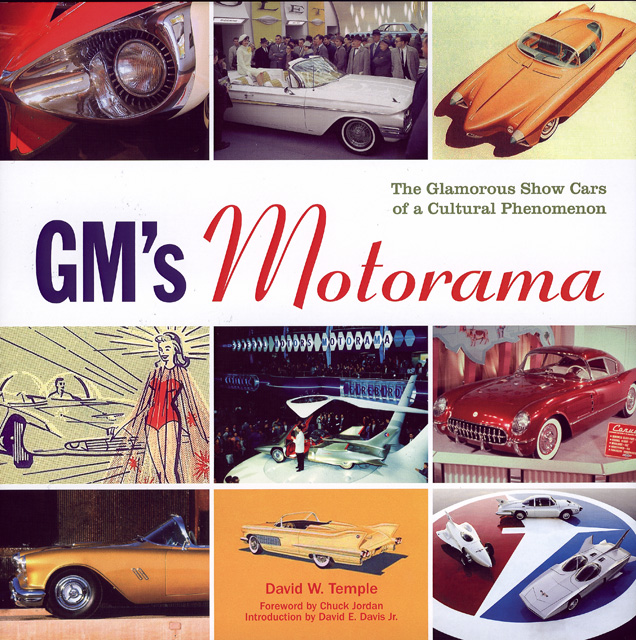

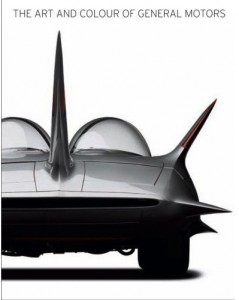

GM’s Motorama: The Glamorous Show Cars of a Cultural Phenomenon

by David W. Temple

by David W. Temple

“My primary purpose for 28 years has been to lengthen and lower the American automobile, at times in reality and always at least in appearance.”

—Harley Earl, 1954

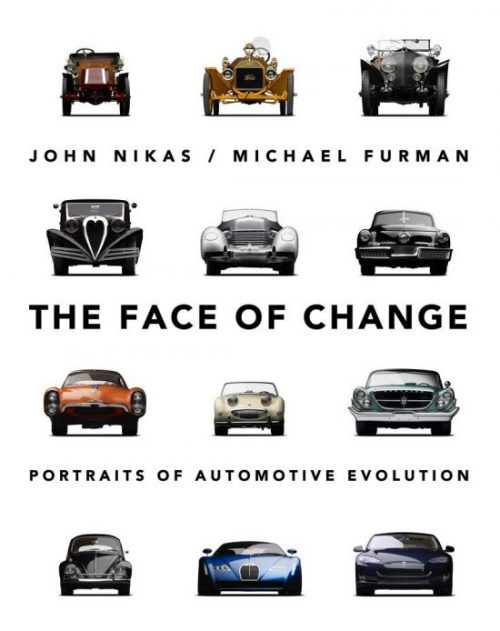

Lower, longer, wider. Often outrageously designed—and often enough outrageously impractical for real-word use (David Davis calls them “comic book fantasies” in his Introduction)—these show cars were the most American of American cars and American lifestyle. There is a certain irony in the fact that so many of their designers, or rather, in the vernacular of the day stylists, indulged their preference for imported European sports cars that crowded the styling department’s garages at a time when (1953) a mere 1/4 of 1 percent of new-car registrations were for sports cars. Whatever they saw in their private cars is not what they put into these dream cars. On the other hand, they understood their market and the zeitgeist.

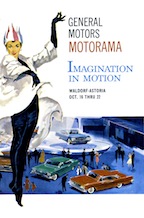

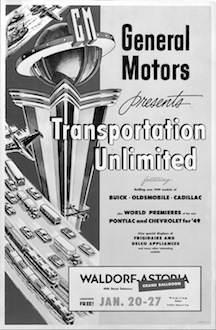

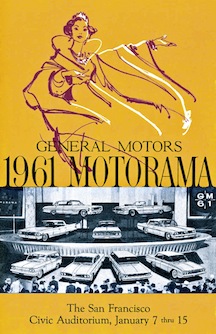

The eight Motoramas staged between 1949 and 1961 were a traveling showroom (except for 1950 were it stayed at its usual starting point, New York City’s Waldorf-Astoria hotel) that brought the General’s products to the people. Author Temple calls them “a cultural event of national proportions,” a sentiment echoed by 43-year GM veteran and former VP Design Chuck Jordan (d. 2010) who wrote the Foreword. All GM divisions—Cadillac, Buick, Oldsmobile, Pontiac, Chevrolet, GMC—got to showcase not only their cars but also parts and non-automotive products. But it is the legendary experimental “Dream Cars” that were the key attraction, then and certainly now. Then, because they featured wondrously new things; now, because the surviving vehicles have in recent years become major moneymakers on the auction scene.

The eight Motoramas staged between 1949 and 1961 were a traveling showroom (except for 1950 were it stayed at its usual starting point, New York City’s Waldorf-Astoria hotel) that brought the General’s products to the people. Author Temple calls them “a cultural event of national proportions,” a sentiment echoed by 43-year GM veteran and former VP Design Chuck Jordan (d. 2010) who wrote the Foreword. All GM divisions—Cadillac, Buick, Oldsmobile, Pontiac, Chevrolet, GMC—got to showcase not only their cars but also parts and non-automotive products. But it is the legendary experimental “Dream Cars” that were the key attraction, then and certainly now. Then, because they featured wondrously new things; now, because the surviving vehicles have in recent years become major moneymakers on the auction scene.

A key person behind GM’s ascendancy to style leader is its first Vice President of Design, Harley Earl (1893–1969). A towering figure not just in terms of output but personality (GM employees quaked in their boots when “Misterearl” stalked the corridors) Earl was also physically tall. In view of the quote above, it is amusing to see him standing next to his 1951 LeSabre whose 50” windshield height barely reaches his beltline. Even the car that, for all practical reasons, is considered the first concept car, his 1938 Buick Y-Job, stood only 58” tall. The book, naturally enough, starts with Earl and while it gives a detailed biographical and professional account does not probe deeply into an important notion of his—the Designer as agent of change; the Designer in the world and of the world; the Designer with ideas and personality big enough to change the way people see the word, interact with the world, forever change their expectations; the Designer as magician; as Superman. (A particularly good book on that subject would be Stephen Bayley’s Harley Earl, Taplinger 1991, ISBN 0800838025). Without these convictions the GM concept cars, even the production cars and especially the Motorama shows would not have come about.

A synopsis of the role of the experimental car and the eight Motoramas and how they advanced GM’s agenda is followed by a chapter-by-chapter photo-intensive treatment of each GM division and its show cars. This includes the one non-passenger dream car, GMC’s 1955 L’Universelle delivery van. Closing chapters examine the reasons behind the winding down of the Motoramas and modern-day concept cars since 2003.

A key point of Temple’s is that the Dream Cars were “laboratories on wheels” rather than gratuitous exercises in design for design’s sake. Once upon a day, automatic headlight dimmers and moonroofs were as novel as GRP (glass-reinforced plastic aka fiberglass) and adjustable suspensions—the Motorama cars tested the waters for many of the things that today are standard fare. While turbines are still unfeasable/impractical, drive-by-wire is actually reality.

The focus of the book is on the cars and their styling and technical features. Except for occasional references, little is said about the “show” aspect of the shows—the dancers, the theatrical effects, the “grasshopper” grabber arm, the innovative displays (cars cut open, hanging from the ceiling etc.) Appended is a most useful listing of the individual 1951–61 show cars and their status as of 2006. The other Appendix lists show dates and locations (US only, not GM Canada); the Index lists all cars and key people but is otherwise meager.

The many archival photos do the subject fully justice. There are quite a number of full-scale clay models (another innovation Earl pioneered) and construction and detail photos along with the odd brochure, ad, and drawing. The photos are sharp, well reproduced, and captioned and credited.

The many archival photos do the subject fully justice. There are quite a number of full-scale clay models (another innovation Earl pioneered) and construction and detail photos along with the odd brochure, ad, and drawing. The photos are sharp, well reproduced, and captioned and credited.

The book, incidentally, is the offshoot of a series of three 2003 articles (“Fate Unknown”) about the missing GM Motorama cars that ran in the now defunct Car Collector magazine. Temple has been writing for that and other magazines as a freelance automotive photojournalist for over 20 years and is involved in a multitude of ways in the vintage-car world. This book is not intended as the last word on the subject but rather a consolidation—and correction—of the bits and pieces known so far.

Copyright 2015, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter