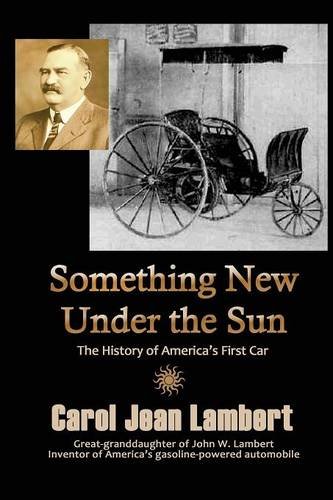

Something New Under the Sun, The History of America’s First Car

[Considering that this is not a subject of which general knowledge can be assumed—which is the whole reason this book was written—we shall offer a bit more background than we normally do in our book reviews.]

In January 1891, professional inventor John Lambert built the first gasoline-powered car in America. It was a cleverly designed three-wheeled buggy powered by a one-cylinder engine that drove the rear wheels through a variable ratio friction disk transmission. Both the engine and transmission were designed and built by Lambert in his Ohio farm equipment factory. The frame of the tricycle was purpose-built to function as a car, cradling the engine and transmission neatly under the passenger seat. The vehicle’s single front wheel was awkwardly steered by foot pedals. The infinitely variable transmission allowed the engine to run at its best rpm while providing both smooth starts and acceleration up to about 15 miles per hour.

Well designed and engineered, the durable car proved itself drivable around town, in hilly country, and across open fields. The transmission provided a very low gear ratio for steep hill climbing even when equipped with its small single-cylinder engine of limited horsepower and torque. Steering with your feet, however, was evidently not practical and contributed to the first auto accident when Lambert careened out of control after hitting a tree stump, eventually colliding with a hitching post in his hometown of Ohio City. All in all, Lambert’s first car was an original and truly unique design that obviously needed a bit of perfecting.

As reliable as this vehicle was, it attracted no buyers even after more conventional steering was added. As a result, Lambert dropped the idea of manufacturing cars, and shifted his efforts in 1892 to manufacturing the car’s patented gas engine as a stationary powerplant for farmers throughout the Midwest. It was not until 1902 that he began to manufacture cars for sale. Interestingly, the 1902 car retained his infinitely variable transmission, but now had four wheels and a conventional frame, suspension, and steering design. The variable transmission would remain a sales feature for the life of the Lambert Automobile Company, 1902–1917. Other car companies licensed the transmission until it gradually faded from commercial acceptance due to ever increasing horsepower and torque, and the bothersome preventive maintenance requirement necessitating the replacement of the transmission friction disk every 3,000 miles.

This 152-page paperback book opens with a Table of Contents, followed by an Introduction, then 10 Chapters and, at the very end of the book, a Gallery of Images. No Index, which makes using the book as a historical reverence source difficult. The 10 photos in the Gallery of Images are almost all dark and badly reproduced.

I learned about this book while reading an interesting article about Lambert and his car company in the Horseless Carriage Gazette. The magazine used several excellent photos to show the types of vehicles that Lambert produced, a few of which were also used in this book. The Gazette’s photos were all clear, and therefore informative, including an excellent picture one Lambert had taken in 1891. It’s unfortunate that the very same 1891 picture is so poorly reproduced on the cover of this book dedicated to the car’s historic importance. The decision to group the photos together at the end of the book seems counterproductive. It’s as if the photos are a bit of an afterthought, and not expected to be overly important to readers.

Carol Jean Lambert, the book’s author, is the great-granddaughter of John Lambert, and her graceful and familiar writing style makes the text read more like a family memoir than a historical account of what is fundamentally an engineering topic. Although the historical facts are there, they do not dominate. The author seems more interested in describing what people were probably thinking about and experiencing emotionally than what they did and how it was done. She is at her best when imagining the feelings of family members, as opposed to operational and/or construction descriptions of the various Lambert vehicles, which included trucks, busses, and light rail cars, all powered with appropriate versions of his patented variable speed transmission design.

Carol Jean Lambert, the book’s author, is the great-granddaughter of John Lambert, and her graceful and familiar writing style makes the text read more like a family memoir than a historical account of what is fundamentally an engineering topic. Although the historical facts are there, they do not dominate. The author seems more interested in describing what people were probably thinking about and experiencing emotionally than what they did and how it was done. She is at her best when imagining the feelings of family members, as opposed to operational and/or construction descriptions of the various Lambert vehicles, which included trucks, busses, and light rail cars, all powered with appropriate versions of his patented variable speed transmission design.

I found the book interesting, but not what I wanted or expected. I was hoping for a more mechanical view of things, with clear photos showing representative samples of the wide range of vehicles evidently manufactured by Lambert. I don’t feel it’s entirely accurate to subtitle the book a “History of America’s First Car” when it reads more like a history of the Lambert family personalities surrounding the construction of America’s first car, and later on, the operation of the Lambert Automobile Company. The author recounts many interesting insights into what made the inventor and the rest of his family tick, but not enough historical data, including photos, on what Lambert invented for this reader to find satisfaction. More “who, what, where, and when” and less “why” would increase the book’s value, at least for me.

Copyright 2016, Bill Ingalls (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter