X-Plane Crashes

by Peter W. Merlin and Tony Moore

by Peter W. Merlin and Tony Moore

“It felt like being Sherlock Holmes and Indiana Jones rolled into one.”

One way or the other, what goes up must come down. If this happens in an uncontrollable manner there’s usually a crash in the making. Unlike other countries, the US protocols for crash investigation and recovery vary widely. In civilian/commercial crashes it is usually the FAA and NTSB that attend to debris removal, and local, state, and federal agencies from the US Forest Service to the National Park Service have a say in the proceedings. The US military, and in this context the Air Force specifically, does not have any policies prohibiting debris removal by civilians provided no human remains or weaponry remain unrecovered at the site. However, environmental regulations since 1980 pretty much require complete debris removal from the crash site, leaving very little “hard” evidence behind.

Enter, the “X-Hunters” aka the Aerospace Archeology Field Research Team aka Peter Merlin and Tony Moore who co-wrote this book, the first to focus on the subject of finding sites where experimental aircraft went down. Attracted by the intricacy of the research as much as the thrill of finding a piece of history, they have located and documented more than 100 crash sites of exotic aircraft in the western United States, home to both Edwards Air Force Base and Area 51.

It is in the very nature of flight research that untried technology and performance profiles look one way on paper and another in flight. While today computer simulations can minimize risk, it is still the test pilots who have to screw up their courage to “boldly go where no one has gone before” and push the envelope just a little more.

Merlin and Moore in this book focus on incidents from the 1940s through the 1970s, partly because this was a particularly fertile time in flight research and partly because debris then was recovered with less vigor than today. It is, in fact, amazing just what sort of stuff the authors have come across, from nose cones to artifacts small enough to fit in a matchbox. Some of the recovered material is being donated to museums.

It is also amazing to consider that for years Merlin and Moore harbored similar interests and, without knowing each other, even worked at the same airport before a chance conversation brought to light that each, independently, had long been searching for the XB-70 crash site (Moore had found it, Merlin didn’t). In 1992, they joined forces and complimentary skills, and within a few months found the X-15 crash site and several others. Armed with photos and a hunch they set out into the thankfully largely barren and unaltered landscape, and everywhere they went they found something—not by chance but because they did thorough research of primary sources such as official reports and eyewitness accounts and re-interviewing survivors and local residents.

Before you get all sweaty-palmed and gather up your prospecting gear, realize that Merlin and Moore don’t give locations; no maps, no coordinates. Whether this is done out of a concern that the crash sites would be compromised or simply to keep the fruits of their labors close to the chest, you’ll have to strike out on your own or join some of the several organizations that partake in this hobby. While sheer stamina and tenacity (stubbornness?) are key qualities in a wreck searcher, it doesn’t hurt that Moore is a certified Aircraft & Powerplant tech and Merlin has a BS in Aeronautical Studies which enables them to tell a bottle cap from a titanium keyhole cover and a flight control surface from a trunk lid.

You may recognize either author’s name from any number of Television shows, magazine articles, or books. Over the years they have turned their amateur interests into professional careers, Merlin as archivist and historian at NASA’s Dryden Flight Research Center and Moore, who once also worked at Dryden as an audiovisual archivist, as museum assistant at the Air Force Flight Test Center Museum at Edwards Air Force Base.

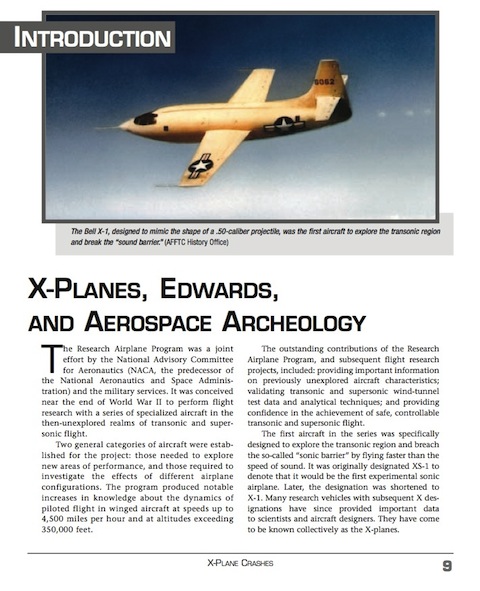

The book begins with an explanation of the Research Airplane Program, the joint effort of NACA and the military to develop and field specialized aircraft especially for transonic and supersonic applications. The logic behind the “X”-planes bearing that designation is explained (and not without humor: “If you’re not confused yet, you haven’t been paying attention.”), as is the founding of Muroc Army Air Field and its subsequent development into the world’s premier test site of which the Dryden Flight Research Center is now a prime tenant.

The bulk of the book is devoted to specific incidents, each describing the role and purpose of the vehicle being tested, development highlights, the immediate backstory to the crash, and ending with a first-hand account of the team’s search for the site and its discoveries, along with a bit of field craft. Each aspect of the story is suitably illustrated, either with archival images (all credited) or Moore/Merlin’s own. Aircraft profiled include the YB-49 and a pair of N9M flying wings, X-1A, X-1D, VB-51, XB-70, SR-71, YF-12, U-2 prototype and more.

Appended are two lengthy lists of Muroc/Edwards and Watertown/Area 51 crashes providing date, aircraft type and serial number, and brief comments. There is no Index which, coupled with the rather vague Table of Contents, is a real loss.

The publisher offers the whole book as well as individual chapters as downloadable files. Note that NASA makes available a free download of a related 2012 publication co-authored by Merlin, Breaking the Mishap Chain: Human Factors Lessons Resulting from Aerospace Accidents and Incidents (NASA SP-2011-594).

Copyright 2012, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter