The Original Ford GT 101

How the first GT came into existence – and how it was recreated

by Ed Heuvink

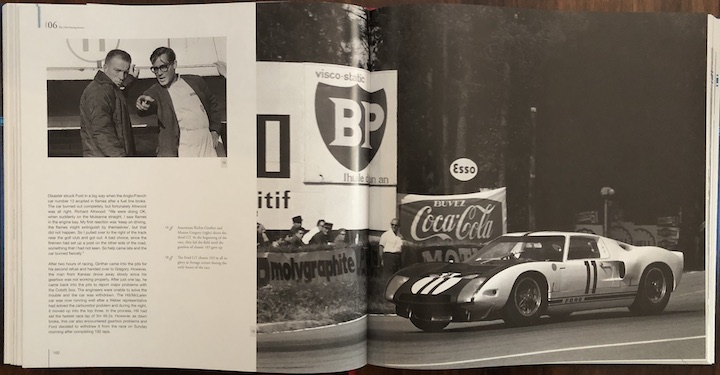

“For the new Ford GT it was a horrible first outing. With the actual 24-Hour race just eight weeks away, the team in Slough had a big challenge in front of them to find improvements.”

Given the supreme, superlative, stunning outcome of the race the quote refers to it is easy to forget how difficult a birth this was, and not just in terms of building a race car.

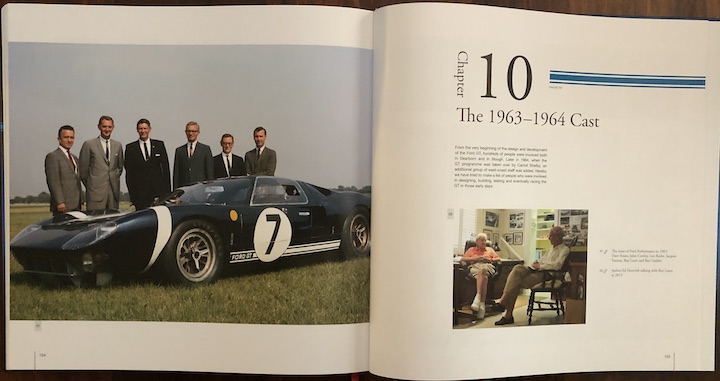

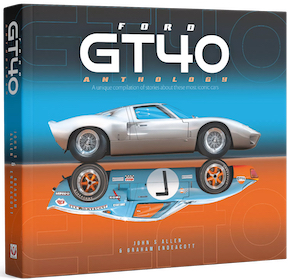

Published in 2016 to commemorate the 50-year anniversary of Ford’s first overall win at Le Mans (which was also the first overall win for an American constructor) this book by a well-established Dutch motoring journalist deals with the very first of the 12 Ford GT prototypes.

The epic win and the epic model are worthy of books any time and, indeed, there is no shortage of literature about them but what makes the Heuvink book extra special is that it introduces into the record a fuller account of the quite unique story of a private collector commissioning in 2013 the recreation of chassis 101 that was so heavily damaged during a 1965 test that it was written off. For all practical purposes it ceased to exist although many of its bits found their way into subsequent cars. That said, even what Heuvink does offer here leaves quite a lot unsaid about the man behind that project. Considering that he—Swiss businessman and vintage racer Claude Nahum who has a serious car collection (multiple GT40s and other delectables, not to mention thousands of diecast models)—is a dyed in the wool car guy who likes nothing better than to talk cars and who has a sterling reputation for being accessible to any and all at races and concours, one must assume that this low-profile treatment is intentional. Our loss . . .

With a Foreword by Henry Ford III and an Introduction by race drive Richard Attwood, about four fifths of the book cover the origin story of the Ford GT and then the technical development of the prototypes. Even the uninitiated will recognize the names of Ford and Attwood as native English speakers and will therefore wonder why their texts read so wooden. Their peculiar syntax and word choices are surely related to this book being a German production, and even with an English-speaking editor (John Davenport, a McKlein regular), their English reads as if had been translated from German. No biggie, but something that begs explanation.

The acrimony between Ford and Ferrari in that era is of course well known and the stuff of legend. The book offers enough background to bring the newbie up to speed but will probably leave the well-read enthusiast cold. This is also true in regards to the cursory treatment of Ford’s overall racing activities and philosophy, but then it needs to be remembered that these nuance- and detail-rich items are in this book only preambles to the GT story. It is probably not too much a stretch of the imagination to think that a foreign commentator such as Heuvink cannot be expected to be fully conversant or current with, say, the changing understanding of the early days of NASCAR and its rather misunderstood bootlegging connection when even native writers are guilty of still flogging story lines that really need to be expunged. Again, no biggie.

The origin story of the GT is critically connected to an item of historic import, the planned Ford-Ferrari partnership (1963). The reasons it didn’t come to pass and instead spawned extreme testiness on both sides have much to do with who said what to whom. And here Heuvink’s read (that it was Enzo Ferrari who took the initiative to reach out to Ford Europe via the German consulate in Milan, p. 29) is crucially different from the newest and in most ways most thoroughly parsed Ferrari history (dal Monte’s Enzo Ferrari, p. 591ff, published the same year in its original Italian as this book [2018 in English]).

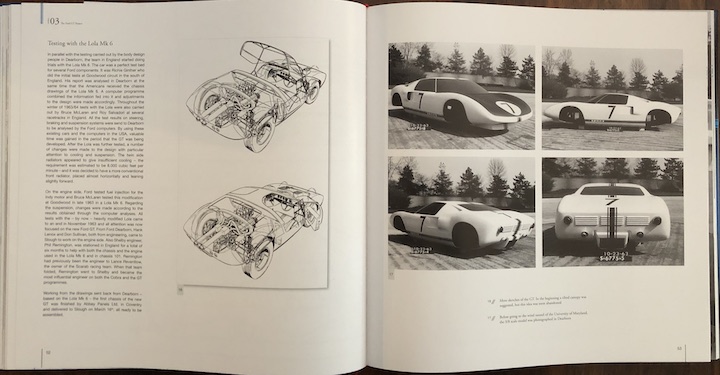

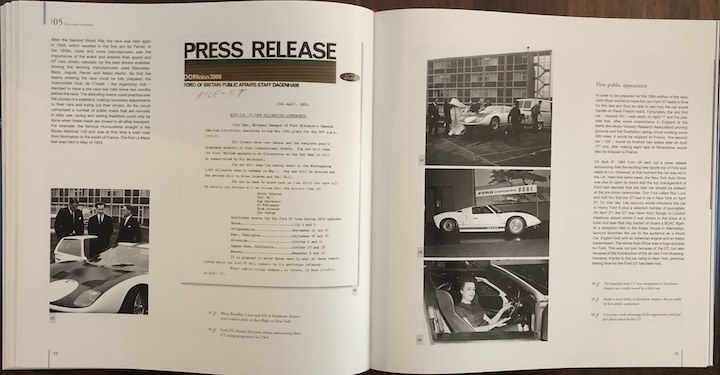

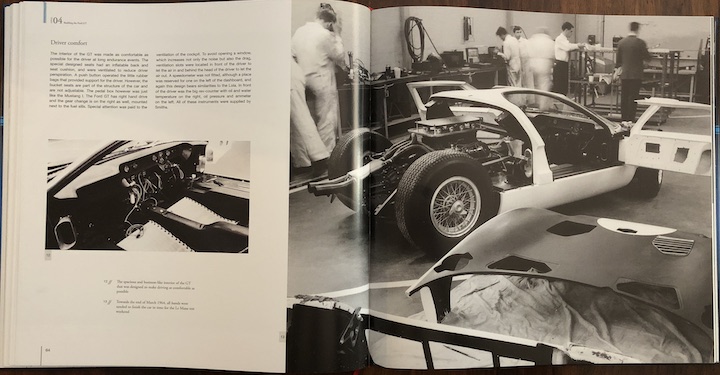

Once the focus shifts from the Lola/Mustang ancestry to the actual building/testing of the GT and the 1964 racing season, Heuvink’s report is brimming with useful detail such as driver reports and excerpts from interviews with principals etc.

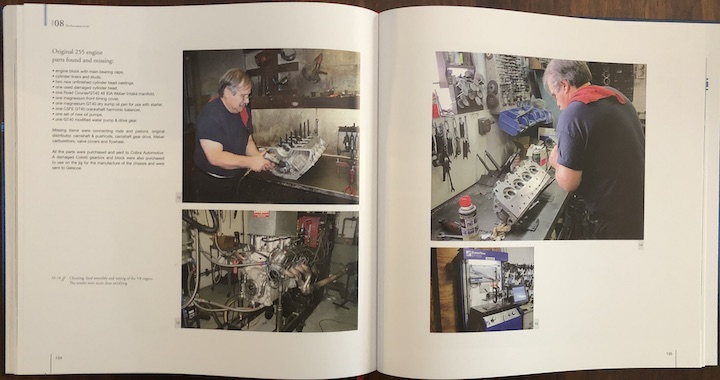

The last fifth of the book deals with the 101 replica or “tribute” car, offering good insights into background matters such as the difficult sourcing of parts, the people involved, and engineering/manufacturing challenges. Ford GT fans who followed this development in 2013–15 will in vain look here for definitive answers to, for instance, the tantalizing chain of custody of the 1963 “wooden chest of” original drawings/blueprints that the builder of the new car (Gelscoe Motorsport) acquired from engineer John Etteridge (who had gotten them from John Wyer who had been asked by Porsche to “get rid of them”. . . you can smell there is a story here!!). Nahum had been trying for years to buy the drawings from Gelscoe so as to scan and preserve them—and Gelscoe finally relented, IF Nahum ordered a replica of 101 from them. If not today then in the future readers/researchers will go 15 rounds over who said what to whom so the polite thing would have been to give a full account here.

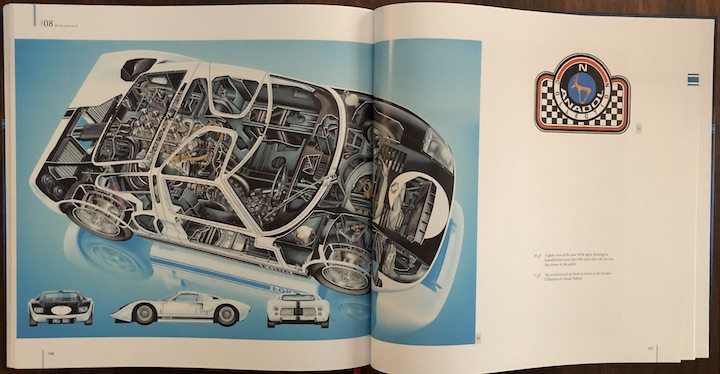

On the illustrative side the book is very strong, including several cutaways and sketches, many close-ups of components, realia such as advertising material, and a good number of photos that are new to the record. Being a McKlein offering, the book is beautifully produced: oversize square format, good paper and printing, crisp design, and excellent photo reproduction—even a rounded spine and a ribbon bookmark!

Incidentally, Heuvink/McKlein have done another book (also with an Attwood foreword) about a car in Claude Nahum’s N-Anadol Collection, Alan Mann Racing F3L/P68 (ISBN 9783927458970). And just to illustrate how easy it is to be thorough we offer this snippet of background: it’s called Anadol (maker of Turkey’s first domestic mass-produced passenger vehicle, in 1966) because Claude’s father Bernar played an important role in the company, brother Jan designed the Anadol “Bug, and Claude/Klod raced them and led the team that developed their Wankel motor. And the N, well, you can figure that out on your own.

Copyright 2018, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter