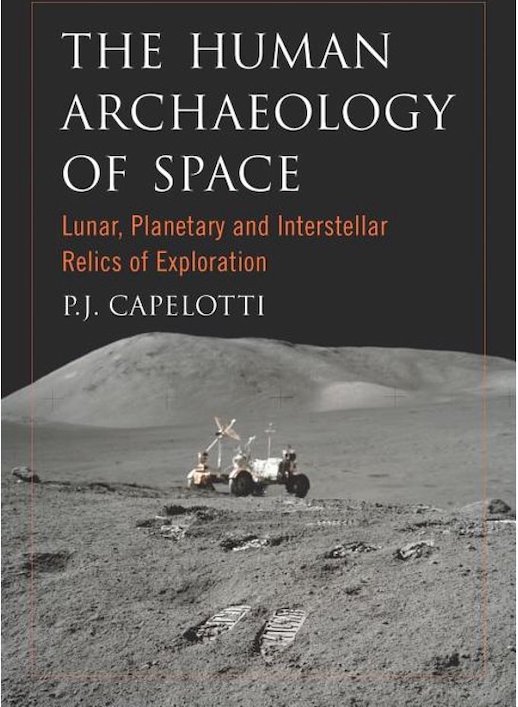

The Human Archaeology of Space

Lunar, Planetary and Interstellar Relics of Exploration

Lunar, Planetary and Interstellar Relics of Exploration

by Peter Joseph Capelotti

Dr. Capelotti is an assistant professor of archaeology at Penn State University’s Abington College where he concerns himself with both terrestrial and aerospace archaeology. In this book he successfully achieves his goal of gathering “into a single source the data on the artifacts that Homo Sapiens have discarded in space and place them into the framework of archaeology” because space debris is “directly relevant to human evolution.” This may not be an obvious connection but that’s just why one benefits from books like this: zee little gray cells of your brain will be stimulated!

This book is fascinating on two levels: the historical and the philosophical.

The historical: it was fun to read the listings of space launches that are now piles of dead technology scattered across the face of the moon, the planets, or left drifting through space. A surprising number ended up crashing, missing their targets, or simply disappearing into the void. I’d forgotten that it was the USSR that was first to land on the moon, Mars, and Venus. The US was the first to get back from the moon, but just barely. While Neil Armstrong was busy being the first man to set foot on the moon, the Soviets were concurrently trying to send moon soil samples back to Earth on Luna 15. The Russian robot moon lander collected the soil, but failed to lift off to beat the Americans back to Earth.

The list of countries that have reached the moon with spacecraft since then has expanded to include the European Union, Japan, China, and India. The total weight of crashed or abandoned objects on the moon’s surface now totals 190 tons of debris, roughly equivalent to 150 automobiles! All that crash site debris is now worth a fortune to treasure hunters, collectors, museums, and universities. In 1993 the remains of the Russian Luna 21/Lunokhod 2 lander/rover (still up on the moon) were sold for $68,500 to a private individual. Also auctioned off to the public was tiny sample of moon rock returned to Earth by Luna 16 which sold for $440,000.

The philosophical: Capelotti gives us his thoughts on the validity of university-trained archaeologists controlling all artifact sites. Whether it is nobler to seize and plunder the sites for the exclusive use of the accredited intellectual illuminati of the day, or to allow random non-illuminati artifact gatherers to collect and/or sell the goods to the general public as souvenirs, or, as has been done in the past, burn it as firewood to stay warm on a cold night. Where does freedom end and restriction begin?

Not mentioned specifically, but alluded to tangentially, is the comparison between the current practice of age-dating archeological sites by examining the manufacturing method, materials used, and design style of ancient pots found at the site, just as in a thousand years’ time future archaeologists will be able to analyze a spacecraft’s design style, construction materials, and instrument sophistication to determine when, where, and by whom it was made.

The author also discusses the virtues of robotic versus human examination of crash site remains, and argues that space debris represents a new classification of objects beyond those found in specific geographical regions here on Earth. For Capelotti space debris represents the planet Earth as a whole instead of a specific individual country or culture, countering those who feel space debris is simply an extension of a localized technology being taken into new territory; in this case, space. In practical terms, an extraterrestrial who runs into “our” debris won’t know, or care, if it is Italian or Chinese.

The landing and crash sites on the moon that should be preserved are also discussed by Capelotti. All of them is his answer, but preservation costs and human psychology will undoubtedly play a cruel role. I imagine most people would agree man’s first footprint on the moon is imbued with significant symbolism to be worth preserving and protecting, but what about the 10,000th? Are all footprints created equal? Can future humans be allowed to disturb, buy, or sell anything that has ever landed on the moon? Is it all sacred, even the two golf balls Alan Shepard hit during his moonwalk? And who owns those golf balls today—the US government, Alan Shepard’s family, no one?

Another question this book raised for me: If an archaeological space object is privately or nationally owned and subsequently made part of a protected second-party archaeological park, does the park have to buy the object from the legal owner, or perhaps owe fees to the owner because the space debris is being used to obtain site funding, or as a draw to charge viewers to visit the park? Do the remains of a space crash site still belong to the country of manufacture, or to a private individual who legally purchased the remains? Salvage rights to the items contained in shipwrecks are not without legal recourse by the owners. The same holds true for arrowheads picked up off the ground. Will these established legal precedents extend to space objects?

The book begins with Acknowledgments and a Preface, then breaks into three parts: Lunar Archaeology, Planetary Archaeology, and Interstellar Archaeology, followed by Chapter Notes, a Bibliography, and an Index.

Copyright 2011, Bill Ingalls (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter