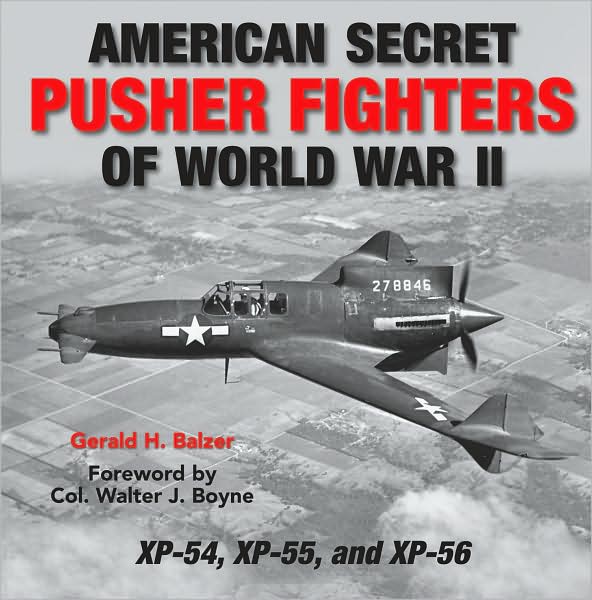

American Secret Pusher Fighters of World War II: XP-54, XP-55, and XP-56

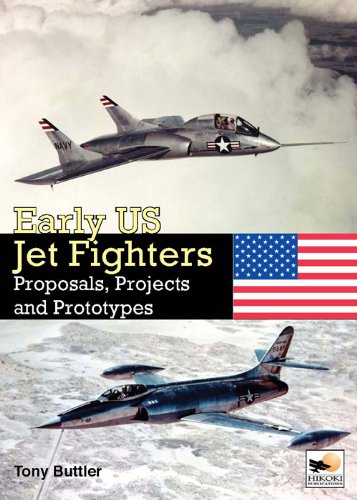

Just look at that cover. Looks like something from a comic book. “Blackhawk Squadron, We See the Bat Signal in the Sky!” Any one of the aircraft in this book are every bit as exotic as the very striking XF5-1 Skyrocket.

My first notice of these aircraft probably came as a result of Ray Wagner’s American Combat Planes (Doubleday, 1960) or William Green’s War Planes of the Second World War: Volume IV, Fighters (Hanover House, 1961). These pusher (i.e. engine is in the back) fighters are actually mentioned in the introduction to Green’s book and the information provided by Wagner only whetted the appetite for more information regarding these unusual and very different aircraft.

Although the wait for more took about a half century, it was well worth it! The book is well-researched and the production values are what one has come to expect from the publisher, Specialty Press. The photographs in the book are plentiful and well-placed, just where they need to be, which is something not at all to be taken for granted.

The book is simplicity itself: only four chapters, one providing an introduction covering the origins of the pusher fighters and then a chapter devoted to each individual aircraft. The first pages of the introductory chapter give a broad overview of Army aviation until the proposal was released that resulted in these three unique fighter planes. That proposal was “Request for Data R40-C” which was released during Fiscal Year 1940. This proposal differed from the usual circulars that were sent from the War Department to the aircraft industry regarding the specifications for the aircraft the Army Air Corps wanted: it wanted industry to “think outside the box” as we would say today.

The basic requirement was for a single-engine, single-seat fighter (a pursuit plane in the jargon of the day) having at least four guns (.30-caliber, 50-caliber machine guns and/or 20mm and 37mm cannon) of a new design; the aircraft had to be capable of operating from a 3,000-foot sod airfield surrounded by 50-foot obstacles. In addition, it had to have speed, 425 mph at 15,000 feet (reduced from the original 450 mph, but with the optimal speed being 525 mph at that altitude). It was, in essence, an opportunity to begin with a clean sheet of paper and let the imagination shift into high gear rather than have to deal with the usual constraints that the AAC Circular Proposals contained.

The basic requirement was for a single-engine, single-seat fighter (a pursuit plane in the jargon of the day) having at least four guns (.30-caliber, 50-caliber machine guns and/or 20mm and 37mm cannon) of a new design; the aircraft had to be capable of operating from a 3,000-foot sod airfield surrounded by 50-foot obstacles. In addition, it had to have speed, 425 mph at 15,000 feet (reduced from the original 450 mph, but with the optimal speed being 525 mph at that altitude). It was, in essence, an opportunity to begin with a clean sheet of paper and let the imagination shift into high gear rather than have to deal with the usual constraints that the AAC Circular Proposals contained.

The account of the results of R40-C are interesting to read, providing an excellent commentary on how the competition narrowed down to the three winners, entries submitted by Vultee Aircraft (Model 70 Alt. 2), Curtiss-Wright (Model P-249C), and Northrop Aircraft (Model N-2B). However, as interesting as that is, the overview regarding engine development and allocation for the aircraft proposed under R40-C is even more fascinating to read. These well-written pages make clear that issues regarding the engines were key to the fate of the aircraft proposed under R40-C.

The winner of the R40-C competition was the Vultee XP-54, the “Swoose Goose.” The height of the XP-54 led the designers to develop an elevator seat for the pilot to enter the aircraft. While this also allowed the pilot to make an emergency egress from the aircraft that would save him from striking (at least in theory . . .) the propeller at the rear of the aircraft, it also added both weight and complexity, especially in regards to cabin pressurization. A striking-looking aircraft, the XP-54 was largely the victim of, among other things, weight that crept up and up and up. Another key problem it shared with the other pusher fighters was that is was a “paper plane” being designed around a “paper engine” that never appeared.

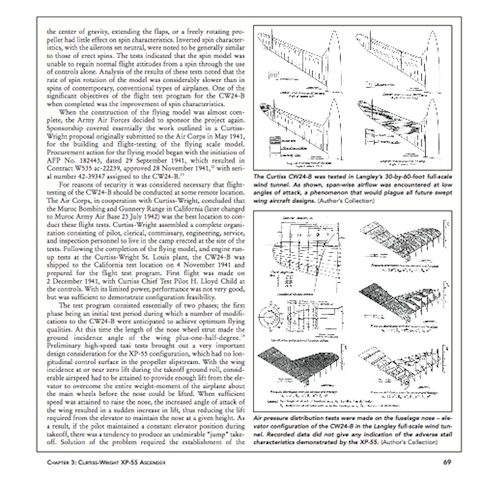

The Curtis-Wright XP-55 “Ascender,” a product of the company’s St. Louis Division, was basically a derivative of an earlier pusher concept, the CW-24-B. The swept-wing design, the control surfaces placed on the nose, and the location of the pusher engine all meant that it was a radical departure from any of the other aircraft in the skies over St. Louis where it made its initial test flights. However much promise the XP-55 may have seemed to offer, the usual litany of problems—especially its stall characteristics—doomed the plane to being merely a footnote in aviation history.

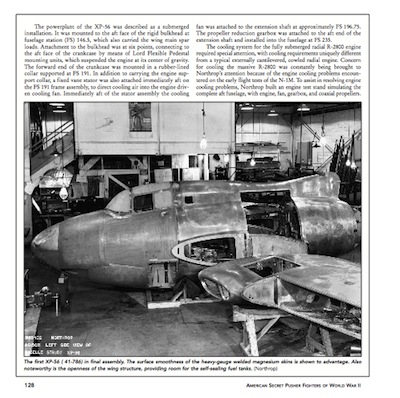

The third-placed aircraft of the trio in the R40-C competition was the one that probably gets the most attention in the book: the Northrop XP-56 “Black Bullet.” Rather than the Blackhawk Squadron, it is exactly the sort of thing that Batman and Robin would use in their flights around Gotham City. Suffice it to say, whatever I thought I knew about the XP-56 paled before what Balzer has put together here. As interesting as all three might be, there is an aircraft in the current Air Force inventory that comes from the lineage of the “Black Bullet”—the B-2 Spirit aka Stealth Bomber.

The third-placed aircraft of the trio in the R40-C competition was the one that probably gets the most attention in the book: the Northrop XP-56 “Black Bullet.” Rather than the Blackhawk Squadron, it is exactly the sort of thing that Batman and Robin would use in their flights around Gotham City. Suffice it to say, whatever I thought I knew about the XP-56 paled before what Balzer has put together here. As interesting as all three might be, there is an aircraft in the current Air Force inventory that comes from the lineage of the “Black Bullet”—the B-2 Spirit aka Stealth Bomber.

This is an excellent book, an impressive effort. It is almost a textbook example of aviation historical research done right and just how difficult that can be. That Balzer, a retired aeronautical engineer (Northrop, McDonnell, TRW) who had served in the Army Air Force Training Command, managed to dig up all that he did is nothing short of amazing. That Specialty Press let this book see the light of day is something for which we should be very thankful. I highly recommend it!

Copyright 2012, Don Capps (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter