1 1/2-litre Grand Prix Racing 1961–65 – Low Power, High Tech

“This is the story of a Grand Prix formula that no British race car constructor wanted and yet which became one they would almost totally dominate.”

A book review should not be a book report, i.e. a retelling of the subject matter but in this case the broader context has remained underreported enough to warrant a few extra words. Moreover, as Raymond Baxter, the 1950–66 BBC motoring correspondent and therefore an eyewitness to the proceedings presented here, rightly says in his splendid Foreword, “ . . . this is not an easy read . . . it is a scholarly history of an exciting, fascinating and technically important period in international racing—it is a classic of its kind.”

In the dying moments of 1960, Denis Jenkinson, the Continental Correspondent for the British monthly Motor Sport, dashed off the final lines of his book A Story of Formula 1 (Grenville, 1960) so that it could be put in the hands of the publisher. The book was essentially his in-depth review of F1 racing from 1954 to 1960, a period during which racing cars had to conform to regulations limiting them to engines with a maximum displacement of 2.5 liters if unsupercharged and 750 cubic centimeters if supercharged—which few took seriously—and using 130 octane Avgas (aviation gasoline) beginning in 1958, which replaced the alcohol-based fuels used previously. It is of interest to note that the longest chapter in the book is entitled “Supremacy of Britain,” a summary as to how Britain, by jingo, emerged triumphant in the final years of the formula, with both British drivers and machines winning championships and dominating their opponents.

On New Year’s Day 1961, a new International Racing Formula 1 came into effect, one the British had vehemently opposed from its announcement in late 1958. The new formula reduced engine capacity to 1.5 liters, outlawed supercharging altogether, and added a minimum weight of 450 kilograms as well as several other items to the regs. Also, for the first time since it was introduced in 1950, the events counting towards the World Championship for Drivers (Championnat du monde des Conducteurs) would now have to use the new Formula 1 in order to be included in the championship. In other words, events such as the annual 500 mile race held at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway would no longer be part of the championship; nor could the world championship be switched to Formula 2 as happened in 1952 and 1953.

Alas and alack, when, despite much moaning and groaning and no end of whining by the British, the Commission Sportive Internationale (CSI) in Paris actually stuck to their guns—they were French and resided on the Continent, after all—and refused to budge, the British teams basically brought a paring knife, albeit a sharp one, to a gunfight. Of the seven championship events in which British teams and Ferrari went head-to-head, the Italians won five and Stirling Moss two. For the final championship event of the 1961 season, the United States Grand Prix held at Watkins Glen, despite no end of effort by race promoter Cameron Argetsinger, Ferrari did not appear, therefore denying the season’s champion, American Phil Hill an opportunity to compete in his home country.

From 1962 to 1965, however, it was Rule Britannia, British drivers winning all four championships, including John Surtees in 1964 in a Ferrari that for its color might as well had been a British machine, being virtually the same in almost all respects to its British competitors. Rule Britannia! Rule the Racing World! But, as successful as Britain may have been during the Twiddler Formula years, as much as it might have developed the hegemony by Albion that still persists to this day, there was something not quite satisfying about it.

The cars being developed for the 1.5L Formula 1 were leading towards the incorporation of more and more sophisticated technology in chassis design, tires, and engines which, coupled with the relatively low power available, meant that the cars soon exceeded the lap times and even speeds of most of their predecessors. And while they did it with a certain refinement on the track, something was missing: spectacle.

Meanwhile, sports-racing cars got hairier and hairier, engines bigger and bigger, and there was spectacle galore with brutal, powerful machines competing on tracks from Monza to Le Mans to Sebring to Riverside to Daytona to Silverstone and the Nűrburgring. By 1965, the Ferraris, Chaparrals, Lolas, McLarens, Ford GTs, and Shelby Cobras were providing spectators with all the spectacle they could desire: loud, powerful cars with their tails hanging out as they thundered through the turns . . .

At the end of 1965, the Twiddler Formula came to an end. Originally scheduled to run until 1963, it had been given a two-year extension until 1965. In November 1963, the CSI voted for a new Formula 1 to take effect on 1 January 1966, increasing engine displacement to 3 liters for unsupercharged engines and allowing supercharging back, for engines up to 1.5L, no less, with the minimum weight being raised to 500 kilograms. By 1967 or 1968, it was almost as if the Twiddler Formula had never existed. Few racing fans seemed to have much nostalgia for it and even less interest in its history.

In an issue of Road & Track, Jonathan Thompson did a wrap-up of the formula’s five seasons. As 1965 waned into non-existence, Denis Jenkinson did not scribble any words for a publisher waiting to put them into print as soon as possible. In 1974, the Formula One Register (basically John Thompson, Duncan Rabagliati, and Paul Sheldon) produced their first work, The Formula One Record Book (Leslie Frewin), which provided the first detailed record of not just the details of every race that had used the formula, both non-championship and championship, but traced the individual cars by their chassis numbers as well, which was unheard of at the time.

Then, pretty much nothing.

The appearance of this book by Mark Whitelock in 2006 pretty much slipped by me since I was quite preoccupied with other matters in the Sandbox. Initially, skimmed it, set it aside, picked it up later just prior to another excursion back to the Sandbox, and then properly read it. Excellent production values, with kudos to Veloce, once again. Plus, Whitelock does what must be correctly lauded as an excellent job packaging the era into a very readable, intuitive format. Giving credit to where credit is due, Whitelock acknowledges those whose work he assembles and shapes into his 336 pages. That he gives thanks to Paul Sheldon and Duncan Rabagliati for allowing him to use material from the appropriate volumes (7 and 8) in their A Record of Grand Prix and Voiturette Racing is almost by itself enough to recommend this book. Given that the work of the Formula One Register has been appropriated by countless others without even the slightest of nods to its source, it is full points to Whitelock for even thinking to ask Sheldon. The same can be said for his acknowledgements of others who rendered input/assistance.

It should be pointed out that Whitelock commits the same sin that countless others have when it comes to much of the race data: using criteria and terms that were not used contemporaneously in many cases. By any stretch of the imagination, Whitelock is not alone in doing so, and it is not a fatal flaw by any measure. In a way, this is a comment that can be assigned to the Quibble Bin but it does muddy the thought process.

That there is a bit of jingoism in the book is also a quite common phenomenon. And, as is so often the case, the focus is on the world championship rounds, relegating non-championship events to the most cursory of treatment at the end of each chapter. Yes, including those events would have resulted in a very different book, one that Whitelock probably did not intend to write nor Veloce to publish but this lack of context skews our understanding of the era because there is—or ought to be—more to motorsports practice and evolution than the world championship. For those interested in such matters, consult the aforementioned Paul Sheldon/Formula One Register publications as well as Long Forgotten Races: The Formula One Non-championship Races 1954 to 1965 (W3 Publications, 2009; pages 191–322, edited by Chris Ellard).

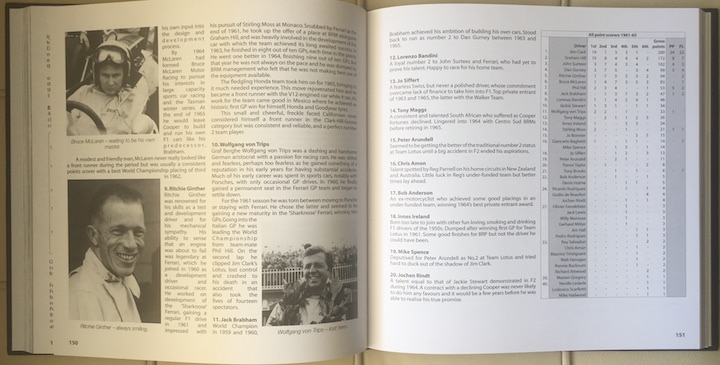

There is one thing that Whitelock does that seems to be indicative of a sort of temptation in books of this kind: an evaluation of the “top drivers.” His book, his choice—but why? It may well be that it is assumed that a reader would expect it. That he places Stirling Moss in first place over Jim Clark who is followed by Dan Gurney might fuel a few heated debates at the pub or in the ether, but does it establish objective “truth”? The book would not have been deficient if that chapter had been eliminated and it is not enriched by having it. Whitelock does present nice write-ups for each of those who make his top 10, offering some useful perspectives and insights.

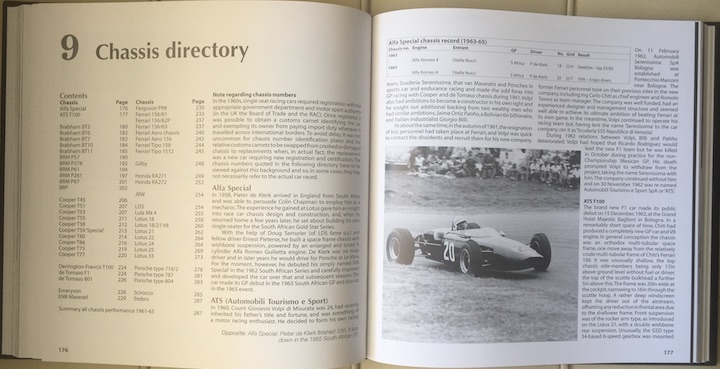

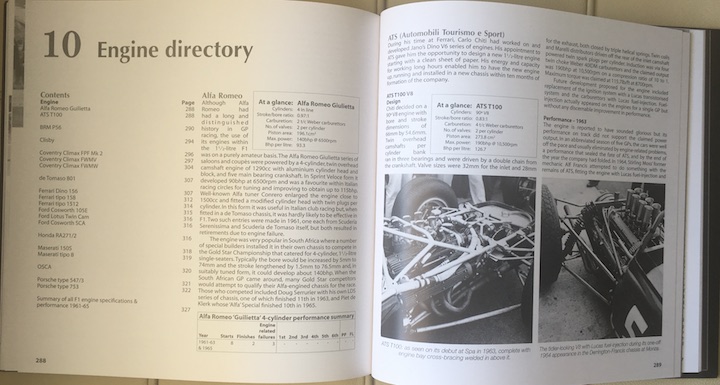

Each of the five season is covered in its own chapter as are drivers (see above), circuits, chassis, and engines. And there is an Index!

One thing this book really does well is to set forth a template that could serve anyone following in Whitelock’s footsteps. It is a truly difficult task to dissect such a complex topic and he organizes his material well, writes with clarity, and abstains from what so often turns into, essentially, techno-porn. All the more laudable considering that this was Whitelock’s first book (which he followed with an exceptional book on the Lotus 18, same publisher) written after retiring from a career in banking. Both topics represent a formative period in his youth, and his affinity for and immersion into the era are evident.

Copies signed by the author are available direct from the publisher.

Copyright 2017, Don Capps (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter