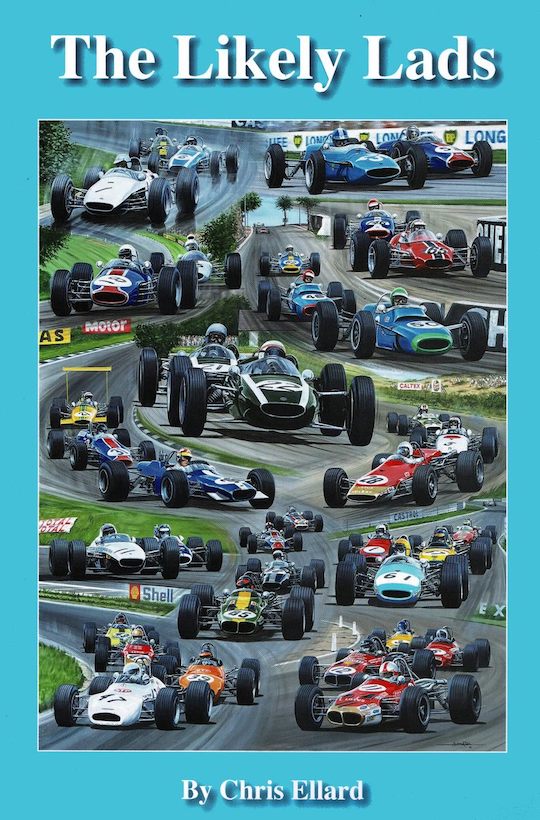

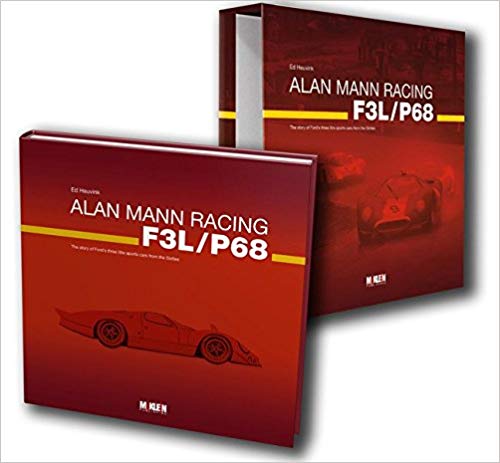

The Likely Lads: From Trimmer to Piquet and from Walker to Warwick

British F3 in the 1970s

by Chris Ellard

by Chris Ellard

“I was quite horrified at the driving behaviour of some of the competitors in the F3 race, the boy Hunt being extremely beastly to my son who, as always, drove beautifully, although his father and I do rather wish he had chosen a more sedate occupation.”

—Mrs LBB Beuttler (mother of F3 driver Mike) in a letter to “Autosport”, about the notoriously eventful race at Crystal Palace in 1970

Have you heard? There’s a new Taylor Swift album. Yes, another one, she’s a busy girl. I’m no Swiftie (as if) but even I know that The Tortured Poets Department will be exquisitely produced, the lyrics will rhyme perfectly, and the musicianship will be startling. Shame about the missing apostrophe though, Taylor.

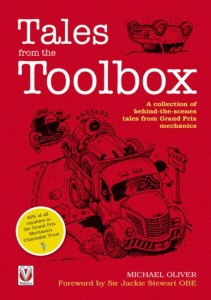

OK, so you’re wondering what Tortured Poets has got to do with a book about Formula Three racing. Well, if this book were an album, it’d be as far removed from a Taylor Swift title as you could imagine. It’s the literary equivalent of a ramshackle garage band’s jam session. It is awash with typos, the punctuation is shocking, it has no coherent narrative and its page design is terrible. But here’s the thing—it’s still worth buying. Look, there are plenty of Taylor Swift albums but this book’s account of Formula Three’s golden era is unique. And if it’s sometimes a literary car crash doesn’t that just reflect the delicious anarchy of the Sixties’ racing scene?

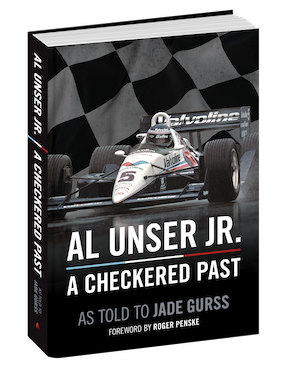

British and European F3 (as I’ll now abbreviate it) was one of the most important single-seater series in the world from the mid Sixties until well into the 21st century. Almost every Formula One driver since the Sixties learned their craft in the hothouse of F3. James Hunt over half a century ago, Ayrton Senna in 1983, and Lewis Hamilton nearly twenty years later. But the golden era was 1 Litre F3, which ran from 1964 to 1970, and which forms the basis of this book.

The book’s 54 (no kidding) chapters are condensed into a modest 217 pages and the pace is frantic, with interviews (contemporary and retrospective), race reports, and anecdotes conveying a blizzard of facts and reminiscences. The author’s obvious passion for his subject makes this book so vivid, and to immerse oneself into its text evokes a glorious period in motor racing history. There was no TV coverage to speak of but, in the UK, the weekly accounts in Autosport and Motoring News were enough to whet the enthusiast’s appetite until their next visit to forgotten circuits like Rufforth or Crystal Palace. There they’d see the next battles being fought between huge grids of gorgeous-looking and -sounding cars from Lotus, Chevron, Brabham and Tecno, as well as a host of now forgotten manufacturers.

A different author might have provided seasonal reviews of the triumphs and tragedies of F3’s stars and coming men, also-rans, and no-hopers. But that isn’t the approach here, because this book evokes its subject much more organically. It’s breathless, often near incoherent but somehow it works, and I was left misty-eyed in recollecting those long-ago summer days when I was even younger than the drivers, and when everything felt possible for both them and for me.

This book can best be described as a mosaic or scrapbook, with one (often unconnected) story following another. Descriptions of events from one season are often juxtaposed with stories of other events which took place years earlier, or later. But, once the reader acclimatizes to this dizzying style, there is plenty to enjoy, and if you lived through that period, then prepare for myriad memories to be triggered. Without this book I’d have completely forgotten about such minutiae as DAF’s participation in the 1966/67 season with the Brabham BT18-based Gemini, using its innovative but unsuited variable transmission. It was a footnote then, just another clever idea that didn’t work, but the passage of half a century somehow endows the story with a gravitas it lacked in period. Or what about the Dave Walker backstory? He was the tough Aussie who is forever stigmatized as the man who could almost walk on water in F3 but who sank without trace in F1. I had no idea he had first raced in F3 many years before he reached the heights of the 1970 and 1971 seasons with Gold Leaf Team Lotus.

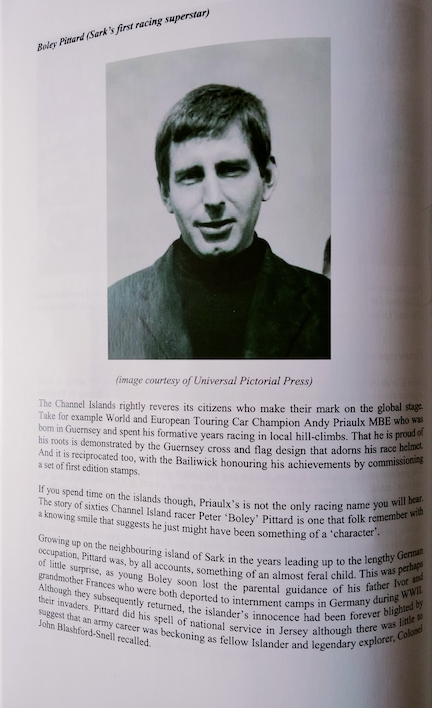

When Pittard’s car burst into flames on a packed grid he heroically drove the burning Lola off to the side to avoid spreading the fire to other cars. None of the other drivers stopped to help him. The race was not stopped. He died six days later.

The Sixties and Seventies are notorious for the appalling toll of driver deaths and injuries, but one tends primarily to remember those deaths and injuries that took place in Grands Prix, at Indianapolis, or Le Mans. But the author reminds us that F3 has a dark past too, thanks to a fatal cocktail of flimsy cars, dangerous circuits, and young drivers who thought they were immortal. For all the glamorous survivors of F3—the Hunts, Petersons, and Bells—there were also drivers like Bo Pittard (left), who succumbed to the burns he suffered in the Monza Galleria 1967 at the age of 31. The author also reminds us that the already dangerous Chimay circuit was made even more lethal by being partly bordered by barbed wire fencing. Or take the curious case of Mike Walker—this charming septuagenarian is still racing, often in Historic Formula Junior in a front-wheel-drive Bond. And back in his F3 days he wasn’t the only F3 driver to crash at Crystal Palace, as the opening quotation attests. But his amazing story is that three years after his big crash at the Palace in 1967 a doctor wrote to tell him that “when I jumped down from the safety barrier to attend to you, you were clinically dead.”

It is testament to this book that I’ve just spent an hour finding my dog-eared program for the 1970 Croft F3 race. It was the first major single seater race I saw, and its 66 entries included at least ten drivers who went on to race in F1, including James Hunt and Carlos Pace. I started this review with a Taylor Swift reference, and I will finish with the title of the Springsteen song which could also serve as this book’s title: Glory Days. Because they really were!

Copyright John Aston, 2024 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter