Horst H. Baumann – Lichtjahre / Light Years

Automobilsport-Lifestyle der frühen 60er

Motorsport Lifestyle of the Sixties

“There has never been a retrospective monograph, a volume to summarize his early black-and-white work or his eminent contribution to the emancipation of color. One searches in vain for his name in specialist works of reference. Unnoticed by the trade and national daily press, photographer and media artist Horst H. Baumann passed away in Düsseldorf in 2019.”

(German / English) Stretch those arms. Fully open the book is almost 2 feet wide (14″ tall) which makes even photos you may have seen already look different.

Haven’t heard of Horst Hermann Baumann? Never mind that the art world had once bestowed the “great artist” label on him and in more than one medium, even in his native Germany he was virtually unknown by the time of his death in 2019, in sadly dire financial straits one would have never expected of his once high-flying lifestyle.

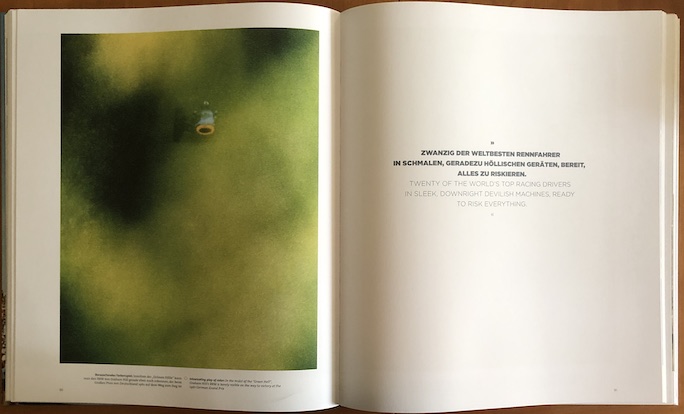

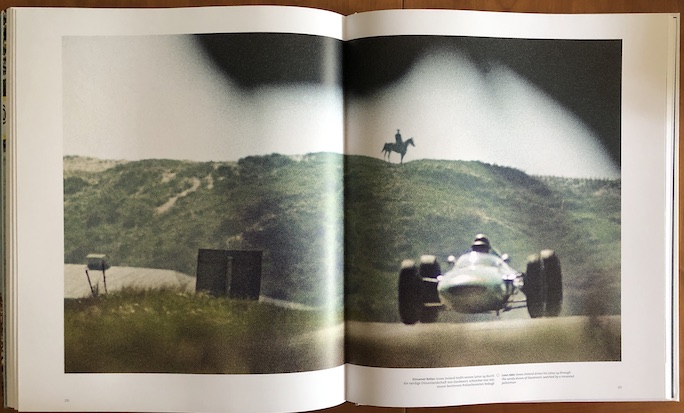

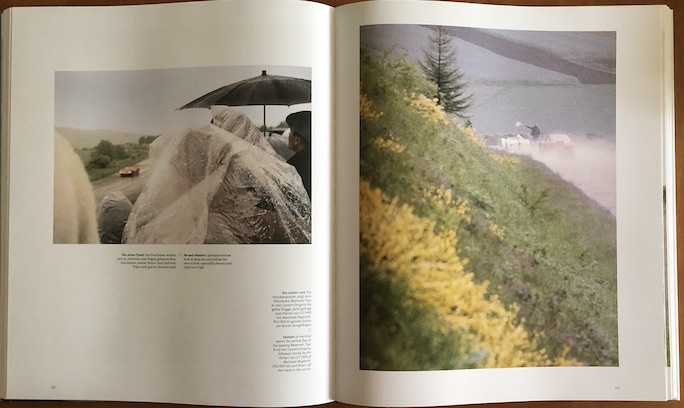

Sure, everyone knows that the Nürburgring is called the Green Hell. But who would have given that image form in THIS way? A photo like this does not happen by accident, you have to plan for it, which means you first have to have the intelligence to conceive of the idea in your mind.

It’ll probably take years for his estate to be cataloged by the gallery to which Baumann’s daughter turned over his many tens of thousands of slides on permanent loan. In the meantime, friends of motorsports photography have this book to enjoy. It isn’t a retrospective so much as as a representative sample of the way he saw things, both literally and also apprehended them emotionally and intellectually.

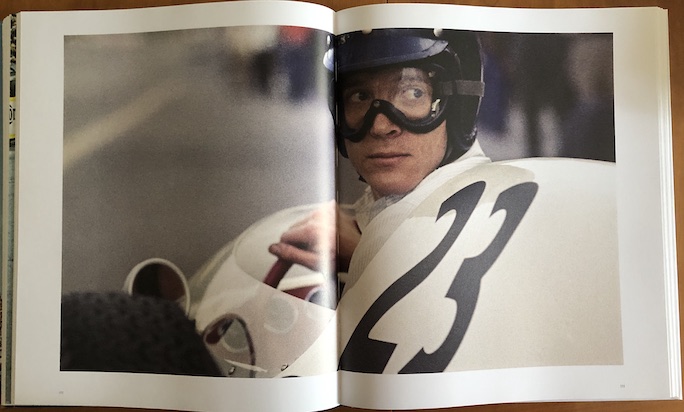

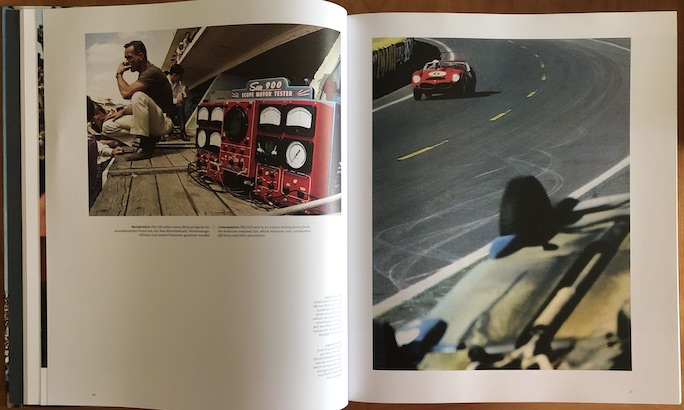

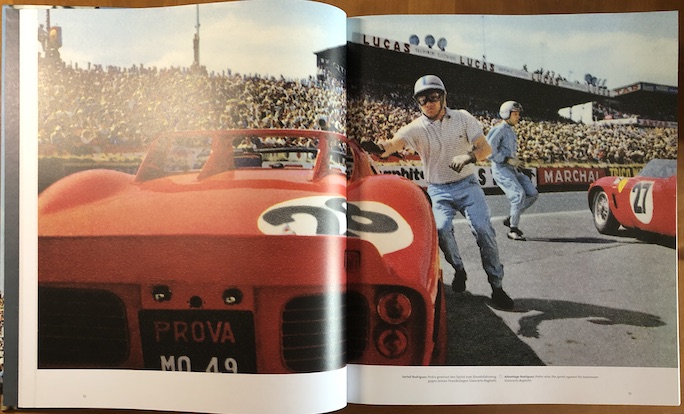

That the book is divided into chapters called Le Mans, Nürburgring, Zandvoort, and Spa is not meant to imply any sort of documentary quality (almost none of the photos, for instance, are dated; the overall timeframe is 1961–64) but is simply an organizing principle. To those who are conversant in the overall flow of photography, the 1960s are a particularly fertile era in terms of camera and film technology, and, insofar as it plays out in motorsports, fairly unfettered access for photographers to anyone and anything. Many storied names were at work then, and even amateurs have left rich treasure troves behind, but it must be said that those Baumann photos that are more than mere convenience snaps have, by and large, an entirely distinctive flavor in terms of composition and field. In that regard one can only bristle in anticipation of the inevitable complaints by some who will look at a good number of these photos and call them unsharp and blurry, or “unnecessary” because they seem to lack obviousness, and in view of the book’s price tag, altogether rather a waste of paper. Wrong; although those who contributed their thoughts to this book could have done much more to manage expectations.

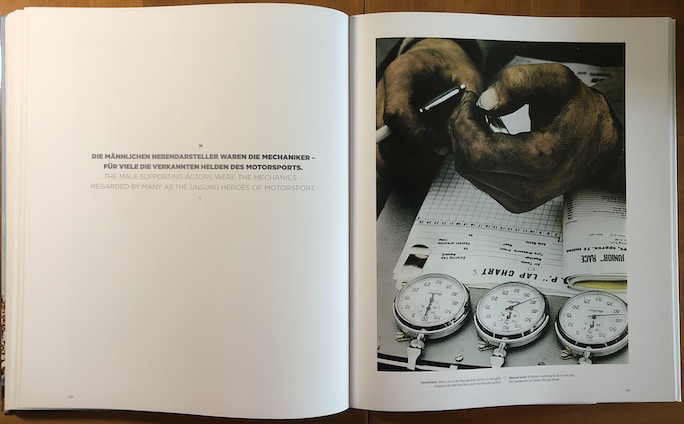

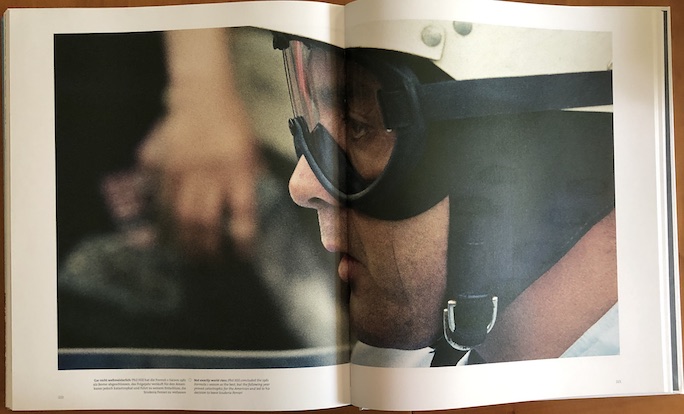

Two unrelated observations. These oily hands belong to a mechanic tasked, during a slow period, with time-keeping duty. Baumann routinely showed up at the track in suit and tie—but he was no stranger to dirty hands, having studied mine construction at university. In fact it was the photos he took on that job, and also the emotive ones he had taken as a teenager right after the war, that prompted other people in his orbit to encourage him to consider photography as a career.

Now, the book was released in November 2020. Baumann died in June 2019 (b. 1934). The book says nothing about it. [1] Was it really too far along its production path to even include a loose-leaf notice? Possible, but one is left to wonder because this publisher has raised vagueness in certain matters to an art form. We have reviewed many of their lovely car books, enough to note that they rarely say anything about the people who make them. In the case of this one, you’re on your own to connect the Uli Hack, Hans-Michael Koetzle, or Etienne Bourguignon dots to Baumann. As so often, this seems like a missed opportunity to establish common ground with the reader. Each contributor has something pertinent to say about Baumann or motorsports and it would only lend weight to the stand-alone pieces they wrote for this book to know that Hack who must have been the project’s liaison to Baumann over the years is a fine artist himself; that Koetzle’s expertise in the history and aesthetics of photography allows him to present Baumann’s oeuvre in a suitably large frame of reference (moreover, as editor-in-chief of Leica World magazine he had ample opportunity to report on Baumann’s use of his favorite “tool”); and that Bourguignon’s chapter “The World of Racing in the Sixties” has heft because it comes from someone with a deep photo archive who can seemingly identify everything and everyone in period motorsports photos.

Those readers who have a long memory will by now be itching to ask the inevitable question: does this book contain anything not already seen in Baumann’s 1965 photo book The New Matadors, written by Ken Purdy and often referred to these days as a “cult item”? Well, about 1/3 of the images are new, and the Indianapolis section is omitted altogether. The reason the new book manages to be a hundred pages longer is mostly because of the size of the photos.

What is true of, say, poems applies to artistic photos too: they don’t say the same thing to everyone, or say the same thing every time. If you have the patience to let these images sort of “sit” instead of just giving them a quick glance you’ll appreciate not just that this book exists but that it is in just the form it is. That the Foreword is by the Chairman of the Supervisory Board of Leica, Andreas Kaufmann, is probably not only a sign of professional courtesy but that there was some corporate support for the book.

Oh, and it’s a limited numbered edition of 1111 and won the 2011 Motorworld Book Prize.

A PS we’d just as soon not have to write . . .

It is not meant as relentlessly belaboring the same point but we cannot very well expect a reader of any one review to have a fully calibrated picture of a publisher’s MO in their minds’ eye so we are forced to spell it out yet another time: Delius Klasing’s book are originally written in German. Superficially, the translations appear fine, in the sense that they yield sentences of correct syntax and, usually, correct equivalents in terms of jargon. But sometimes there are glitches that change the fidelity of the text. Example: In his notes on Baumann Koetzle points out (p. 70) that Baumann was an early adopter of new tech and among the first to use the new “nimble” Leica while, per the English translation, “few photographers still used Speed Graphic or Rollei” when the opposite would have been correct:“most” or “many,” as it is in German but the translator must have lost her way in the typically long, nested sentence, or, worse, not really grasped the point.

- [1] For that matter, Baumann’s website is still up and running—although his last entries are from 2016—and it too doesn’t say anything about being dead, as if he just stepped out for a drink, maybe at his favorite place just across from his apartment where he had that last conversation with Hack the book relates.

Copyright 2021, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter