A Race with Love and Death

The Story of Richard Seaman

“But there it was, preserved for all time, the image of a young British sportsman wearing a swastika around his neck… Dick was standing to attention, it seemed, on the wrong side of history.”

It’s hard to believe that only 30 years separated Richard Seaman’s death in 1939 and sometime rock journalist Richard Williams opining that “It’s a shame no one listens to the Velvet Underground.” British society has changed hugely between 1969 and today, but any changes seem inconsequential compared to the seismic shift from the stifling conformity of the Thirties to the laissez faire hedonism of the Sixties. This book reminds us that society might have changed since the Thirties but the sport of Grand Prix motor racing hasn’t changed as much as we might like to think. And it also reminds us that assertions made about sport’s separation from politics were as naïve in 1939 as they are in 2020.

Richard Seaman was the English racing driver who graduated from the bucolic delight of contesting Shelsley Walsh hill climb in a Riley Nine to the Sturm und Drang of wrestling a Mercedes W 154 around the Nürburgring. This book is not the first one written about his life, and Shooting Star: The Life of Richard Seaman (2000) by Chris Nixon was regarded by many as the definitive work, with both its prose and its photography being widely praised. But I was curious about Richard Williams’ book, as I had enjoyed his rock journalism and TV work, as well as his excellent The Death of Ayrton Senna, written in 1995. His subsequent books on Enzo Ferrari and the 1957 Pescara Grand Prix have also been well received but I am sure A Race with Love and Death will eclipse both. Because it has a full house—family feuds, love, death, and a bygone world of class privilege and inherited wealth.

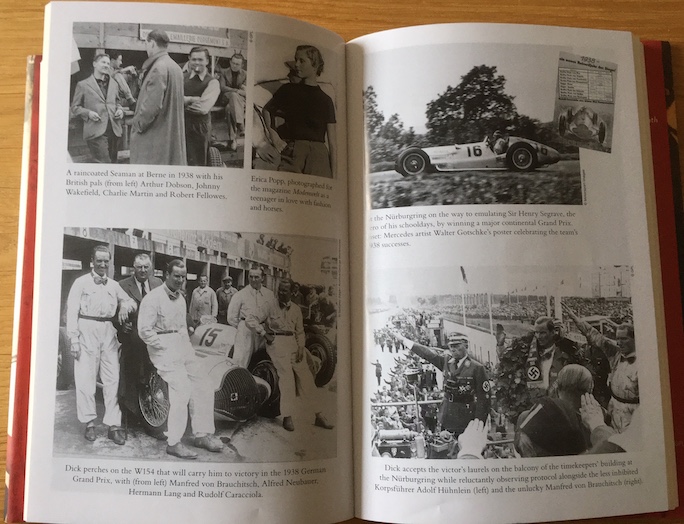

The saga is populated with extraordinary Brideshead Revisited characters like Whitney Straight and Mad Jack Shuttleworth, but the book’s real trump card is the imagery it evokes of a Mercedes W 154—the ur Silver Arrows—being driven to a glorious triumph under a sea of waving swastikas.

The Mercedes race team, together with its rival Auto Union, was funded by Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime with the objective of crushing everything that stood in its way, offering a foretaste of Germany’s intentions and a warning to any nation foolish enough to challenge her. By the time Seaman signed for Mercedes in 1936, only a naïf could have doubted that a proxy war was already being waged through the medium of motorsport. Tellingly, the author even recounts how one of the drivers selected for the team’s “Talent Contest” had “turned up for the test wearing an SS uniform, crashed at the Foxhole, and disappeared from the scene altogether, leaving behind only a torn black sleeve.”

Even if the reader has only a passing interest in this era of Grand Prix motor racing, he or she will already know something about Mercedes’ formidable racecars. The W125’s supercharged straight eight packed a near 600 bhp punch, a figure that no Grand Prix car topped until the Renault V6 turbo finally realized its potential over forty years later. We might know that already, but it was still a shock to be reminded by the author that, in 1936, Mercedes employed no fewer than 380 people in its race shop. Such a figure was not matched again until the late Nineties, and then only by the upper echelons of Formula 1. In 2019 the (take a deep breath) Mercedes AMG Petronas F1 team only employed 100 more staff than its predecessor did 80 years earlier…

A Race with Love and Death has 388 pages, spread over 31 chapters and is book-ended by Prologue and Epilogue. The book is 6″ by 10″ and the design, print size, and font are “just so,” as one might expect from a seasoned publishing powerhouse such as Simon and Schuster. The book also includes two short sections of photographs illustrating key points of Seaman’s life. Perhaps their modest size reduces their impact but, even so, the picture taken at the Spa hotel of a pensive Seaman at breakfast with his wife Erica, just hours before his death, is hard to forget. I do think, however, that the book would have benefitted from an Appendix detailing Seaman’s complete racing results.

After the short Prologue, Williams starts his narrative with the “Mayfair Romance,” the story of how Seaman’s parents met in 1910. Their child was born on the eve of WWI, went up to Trinity College in Cambridge in 1931 and, after his short but meteoric racing career, his life was to end on the eve of World War Two. I confess that this is the first book I have read on Seaman and other, more expert, eyes than mine will need to focus on deciding whether new insights or old truths are to be found in the text. But as this book is targeted towards a wider readership than the typical motorsport title, perhaps my perspective as “informed layman” might actually be a good one from which to review this book?

As Williams recounts, Seaman’s racing career started as so many others did in his era—a hill climb here, a club sprint there, maybe the odd foray to Brooklands—but it quickly evolved into something far more serious. With the invaluable technical expertise of Giulio Ramponi, Seaman graduated from the light-hearted world of chaps messing around in Rileys and MGs to big league motorsport with cars such as the ex-Lord Howe Delage. It was clear, even from his early days, that Seaman only had one ambition in his life, to make a career out of what had started as a pastime and, if that meant persuading his mother to pay the vast amounts needed to fuel the ambition, then so be it. His strategy succeeded, and his decision to contest races such as the Coppa Ciano, the Coppa Acerbo and the Prix de Berne, as well as domestic races at venues like Donington Park, meant that his developing skills were displayed to the right audience. For the 1937 season he signed to race for Mercedes—for a cool 1000 Reichsmarks per month—and, under the storm clouds gathering over Europe, he went on to take victory at the Nürburgring in the 1938 German Grand Prix. Eleven months later he was dead.

Williams’s account of Seamans’s career is thorough and does not fall into the trap, as many racing biographies do, of leaving the reader marooned in an arid waste of race reportage alone. It is the depiction of the people who featured in Seaman’s life which make this book so enjoyable. The reader will encounter the jeunesse doree of the Thirties, faithful confidant George Cosmo Monkhouse, and Mercedes’ Rudolf Uhlenlaut, the urbane counterpoint to tough guy Alfred Neubauer. Williams quotes the latter’s blunt summary of the team talent contest: “One of the candidates had been killed. Our sole consolation was that we had found one driver of world class: Dick Seaman.” But this reader found that even the likes of Manfred von Brauchitsch and Rudolf Caracciola were eclipsed by the author’s account of Seaman’s relationship with the two women in his life, his mother Lillian Beattie-Seaman, and Elfriede “Erica” Popp, daughter of the head of BMW, whom he married in late 1938. Neither comes out of this biography unscathed and, while Erica’s shortcomings may be blamed upon her youth, there is no hiding place for Lillian’s reputation. She was an accomplished social climber and grudge bearer who told her son “Dear boy, I would rather see you lying dead in your coffin than that you should contract this disastrous marriage.” As she was destined to do, of course, but in the company of the reviled Erica, widowed at nineteen.

As for Seaman the driver, on the evidence of this book I found his ambition, courage and ability admirable, and his ruthless approach to success was perhaps even a foretaste of modern Formula 1. Like his racing chum, Buddy Featherstonehaugh, Seaman was able to “imperil the national lets-be-good-losers tradition” by winning races both at home and abroad. But no matter how much allowance I make for his background and the feverish zeitgeist of the Thirties, I found Seaman the man hard to like, and a single incident in 1936 crystallizes my distaste. A house party for Seaman’s racing chums, including Siamese Princes Chula and Bira, was being organized at Pull Court (the country house Lillian had bought—at his insistence—as her son’s twentieth birthday present). But, quelle horreur, it proved impossible to recruit sufficient staff of the right calibre to cater for such important guests. With breathtaking arrogance, the Seamans wrote to the Unemployment Assistance Board to complain that its “generosity” had caused a shortage of willing workers. Gratifyingly, Lillian reported that “the replies we received from the board were most unsatisfactory.”

Seaman may have died doing what he loved but the vale of tears that so many of his family and friends were condemned to inhabit for the rest of their lives would break the stoniest heart. Williams’ Epilogue describes how Lillian “never wavered” from refusing to have anything to do with her son’s widow, but also how, on 25 June of every year until her death in 1948, she placed a notice in The Times commemorating Richard’s death, signed simply “MOTHER.”

This book is Richard Williams’ finest, and I enjoyed it hugely, as the length of this review attests. It deserves every success.

Copyright 2020, John Aston (speedreaders.info).

TAKE 2

Sometimes a book inspires more than one reviewer to render an opinion. Everybody does see different things, or sees things different so every now and then we may post such musings for your enlightenment.

This is a well-written biography and its publisher Simon & Schuster UK Ltd has done a fine job producing a nicely-sized and reasonably-priced book. All of which left me wondering why my reading of it had stalled just a few chapters from the end.

Then it dawned on me; it wasn’t the book itself but rather your commentator’s personal difficulty making a connection with the subject whose life story is being told on its pages. Then too, within a similar timeframe as I had begun reading this book about Richard Seaman I had been reviewing Neal Bascomb’s Faster. If you’re familiar with the same-time-frame but very different story that Faster tells then you’ll perhaps understand my reaction.

Seaman, born in 1911, was the only child of greatly privileged and wealthy parents who had each been independently wealthy before they’d wed two years prior to their son’s birth—a second marriage for both as the prior spouse of each had died. With parents who cruised to Monte Carlo and other exotic places aboard their personal yacht, shopped and dined in London’s finest establishments, employed chauffeurs to drive their Daimlers, and inhabited, as it struck their fancy, one of their various estates, generally living the life of upper crust British aristocracy, it is no surprise that they indulged this precious son with few discernable limitations as author/credentialed sportswriter Richard Williams explains in this book.

Very early Seaman, still but a lad, became enamored of motor racing. He subscribed to the enthusiast publications of the day while also successfully badgering the family chauffeur to teach him to drive. His parents presented him with an MG Magna on his 19th birthday and with that he was off and racing competitively himself. Turned out he was both able and talented behind the wheel with the result that in a scant three years he’d found his way into his first seat in a Grand Prix car.

By 1937, ignoring the ever-growing aggressiveness of one Adolf Hitler, Richard Seaman accepted when invited to become a team driver and full-time employee of one of the German government-financed race équipes, that of Mercedes-Benz, to pilot one of what history now looks upon as “the famed” Silver Arrow Grand Prix cars. A condition of employment, he was required to relocate his residence to Germany. Quite simply, for Seaman his top priority, over-riding most everything else, was driving with the intent of winning races with little consideration for who owned or financed the team and its cars. Although, as photos show, his Heil Hitler salute was usually pretty half-hearted.

Seaman’s mother, now widowed a second time, was upset by her son’s decision but still supportive of his efforts. But when Richard fell in love with and quickly wed a German citizen, the daughter of the founder of BMW, even her maternal bond was insulted beyond her ability to accept. Mother and son became estranged.

And then, of course, my awareness that those concluding pages would tell of Seaman’s death at age 26 as he lost control of his Mercedes W154 while racing in the rain at Spa and crumpling his car and himself into a tree, the book was set aside for a bit.

When I resumed reading I realized how well Richard Williams, who was chief sportswriter for the Guardian and has had several prior books published—on Ayrton Senna, Enzo Ferrari and others—tells Richard Seaman’s story. Of particular note is how deftly he includes and incorporates the events and politics of the times along with a variety of the people involved—all, of course, from a British perspective which makes it all the more compelling and interesting reading. The Acknowledgements and extensive Bibliography attest to Williams’ thorough research. The Epilogue is especially moving for it respectfully brings full circle the people and places significant in Richard “Dick” Seaman’s life.

When an author can connect viscerally with readers of his book, as he did me, (regardless of whether it is a negative or positive reaction) isn’t that an affirmation of that author’s skill at writing the story?

Thus, if Grand Prix history and that of one of its early much-heralded drivers—Richard Seaman—interests you, this is the book for you.

Copyright 2021, Helen V Hutchings (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

I discovered Richard Seaman on YouTube; can’t wait to read Mr. Williams’ book.