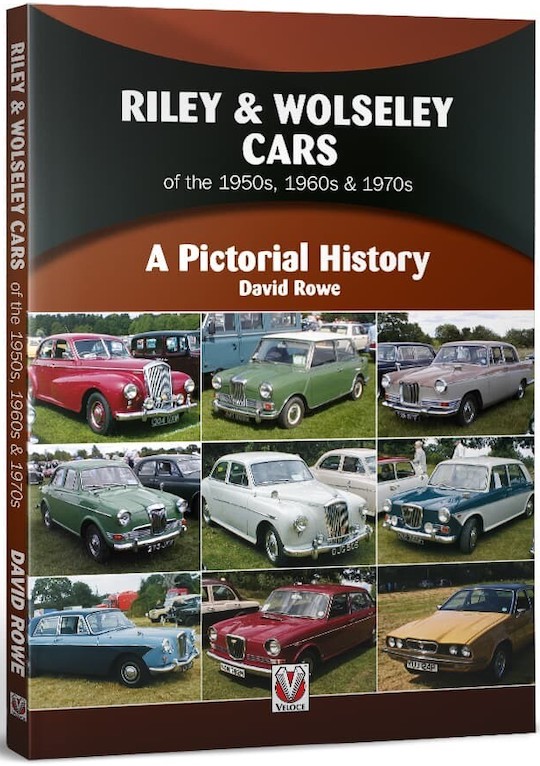

Riley & Wolseley Cars of the 1950s, 1960s & 1970s, A Pictorial History

by David Rowe

by David Rowe

These illustrious marques, both dating back to the earliest cars built in Britain, flourished during their time under William Morris’ ownership, passing into the British Motor Corporation as the two somewhat upmarket brands of that empire until they were allowed to wither and die, in 1969 and 1975 respectively.

Both names are now owned by BMW, and as an historical footnote a merger between the then niche manufacturers BMW and Riley was mooted in the mid-1930s, with Managing Director Victor Riley visiting Munich for discussions.

Real people are behind the firm’s names: Frederick Wolseley (1837–99) emigrated to Australia and farmed successfully while developing sheep-shearing equipment in conjunction with Herbert Austin (1866–1941), and after they returned to England in 1893 the transition to bicycles and then cars was logical. After Wolseley’s death and Austin’s departure to manufacture cars under his own name, the engineering giant Vickers Sons & Maxim took over Wolseley and, sometimes in partnership with other entrepreneurs, a wide variety of often innovative car designs and commercial vehicles was produced. Then came World War One, and alongside other aero engines they built Hispano Suiza V8s under license, overhead camshaft design features from that design showing up into the late 1930s. The postwar slump and high inflation meant doom for this manufacturer of expensive cars, and William Morris (1877–1963) bought the bankrupt company in 1926. Wolseley’s overhead camshaft (o.h.c.) set-up with its vertically mounted generator in the drivetrain was semi-affectionately called “oil hinders charging.” Here the Wolseley brand joined Morris’ own and the semi-independent MG (Morris Garages) and after the Riley family’s car company failed in 1938 it all seemed to have sailed along reasonably well until the amalgamation with Austin in 1952 formed the British Motor Corporation under the authority of Leonard Lord, and much less well after BMC merged again to form British Leyland in 1968 under the leadership of Donald Stokes, one of those Captains of Industry who contributed so much to the demise of it all.

Rileys account for just over 20 percent of the book.

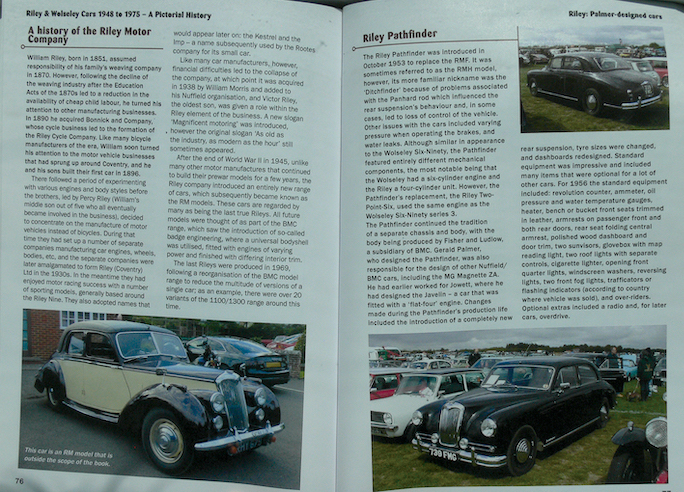

That part of the marques’ history is well covered in Rowe’s book, but the half page covering Riley’s history gives scant mention of the excellent “RM” cars that retained many of the best elements of Riley’s brilliant prewar high performance twin camshaft sedans until 1956.

OK, that quibble out of the way, now to the book. Each model of both brands is well covered with color images, reasonably full technical details even down to gear selection diagrams, color schemes and, perhaps most importantly, production figures. These are particularly interesting; for example, only 3800 Wolseley 18/22s were built during that final 1975 year of Wolseley’s 100-plus year history.

Initial postwar Wolseleys were closely related to the larger Morrises, but with o.h.c. fours and sixes of 1.5 and 2.2 liters instead of Morris’ side valves, but from 1952 the talented designer Gerald Palmer (1911–99) was responsible for both the smaller model similar to the Z-series MGs, and the larger 6/90s which had similarities to the Riley Pathfinder. Those larger cars differed in engines, Wolseleys having the same 2.6L six basis as the Austin Healeys, while the Riley 2443 cc engine which descended from their prewar Big Four produced 110 bhp. Braking also differed, with Lockheed on the 6/90 and Girling on the Pathfinder. Riley’s test drivers at the Industry’s test track had trouble with brake fade, resorting to a gravel pile while the car and driver cooled off during lunch. A Jaguar tester asked about the general well-being; each firm had been assured by Girling that the other manufacturer had no braking problem. 6/90 production was around 11,000 and Pathfinders around 5500 before the rare 2.6, with 9 more bhp than to 6/90 but 9 fewer than its predecessor took over in 1959. It retained the by this time unique right-hand floor gear-change and higher gearing than the Wolseley, but that was the last “big” Riley.

Not the prettiest car, the final Wolseley of 1975.

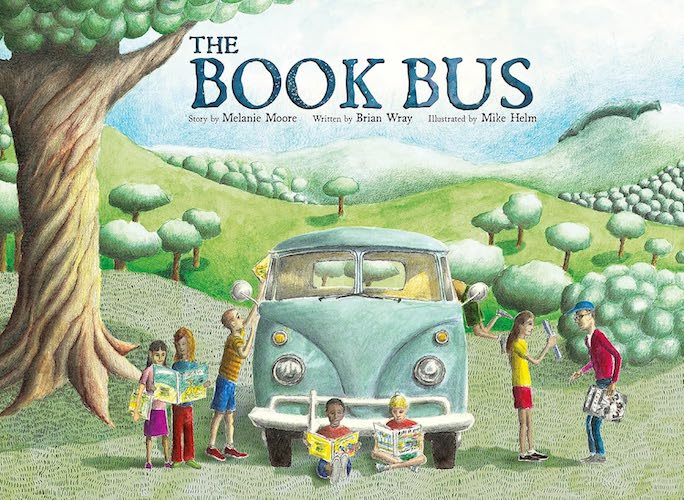

The Wolseley 1500 and Riley 1.5, introduced in 1957, had an interesting history. Originally planned as the successor to the 1948 Morris Minor designed by Alec Issigonis (1906–88), it retained the torsion bar front suspension and good handling of the originally woefully underpowered design, saddled as it was by the prewar 918 cc side valve engine, but was blessed by the B-series BMC engine which could deliver 72 bhp, and for a refreshing change it had a sensibly high final drive ratio of 3.73:1. Your reviewer learned to drive in the family low-light Minor and vividly remembers its features and bugs, such as the pipe from the fuel pump to the SU carburetor clearing the exhaust manifold by an insufficient air gap to prevent vapor lock (eventually cured by, shock! horror! asbestos tape wrapping), the sound of the perennially loose shock absorber mountings amplifying every shock from the unsealed roads of the time, and the misery of grinding in those side valves during the bi-annual decarbonizing. As an ironic footnote, the Morris Minor 1000 was outselling the faintly dreadful Triumph Herald when Stokes killed it off in 1971 in favor of the Leyland product.

From the mid-1960s we move to the era when the engineering challenges mostly involved radiator grille shape, variety of badge, and price manipulation once an extra carburetor, a bit of wood trim and tachometer were attached. Issigonis’ Minis became Wolseley Hornets, Rileys became Elves, while his Wolseleys were called 1100s and 1300s as were their Austin and Morris brethren, but the Riley re-introduced the Kestrel name. That was the arguably first “fastback” saloon introduced on the 1½L six chassis at the London Motor Show in 1932. Resembling a prehistoric Tesla, it had nothing in common apart from its blue diamond badge.

From 1958 the Pininfarina design studio produced a design that now seems under-shod and narrow-tracked, featuring tail fins. More than 100,000 Wolseleys and 25,000 Rileys of those variants of the Austin Farina were sold, and from the variety illustrated in Rowe’s book they retain a keen following.

The Farina shape worked more happily on the bigger Wolseleys which carried on into 6/110 form into 1968, while the later permutations of Issigonis’ innovative transverse engine and front wheel drive formula must have diminished returns by the time the final car was built in September 1975.

Rowe’s book doesn’t mention the Australian-produced 1500/1.5 variants, the Austin Lancer and Morris Major; these 1958–1964 offerings were amongst ever quainter attempts to stop British toes being crushed by the hob-nailed boots of Ford and General Motors there.

The other omission is the production of Rileys in Argentina, Austria, and New Zealand. Some Internet research will confirm that about 11,000 Argentas, derived from the Farina-designed BMC Riley 4/68, were built in Argentina, including a station wagon “Traveller” and a pick-up truck, while the 4/72 was available in Austria as the Riley Comet. In New Zealand the Riley Elf was locally assembled perhaps even after production had ceased in England, and the Hertz franchise ran them as a rental fleet.

Your reviewer and his brother planned their first visit to Britain in the autumn of 1969, and the then Service Manager of BMC, the ex-Riley executive Arnold Farrar, who arranged for a visit to the Competition Department. He edited The Riley Record for the Riley Motor Club, the most recent to have reached far-off New Zealand promising an “exciting announcement;” the cessation of Riley production a little later than our visit was certainly that . . .. As it happened, the obviously ex-British Army Security Bloke looked dubiously at our letter of introduction and after a further check we were turned away; the Motor Show with British Leyland’s secrets was imminent, and brief research will show the paucity of 1969’s innovations.

As all books in this “Pictorial History” series this one is good value and chock full of information unavailable elsewhere, although the writer of the back cover blurb calling it “The ultimate guide for all Riley and Wolseley enthusiasts!” must not be aware of the late David Styles’ (Dalton Watson 1982) and Tony Birmingham’s (Foulis 1965 and 1974) comprehensive books, both of which are well worth finding.

Copyright 2024, Tom King (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter