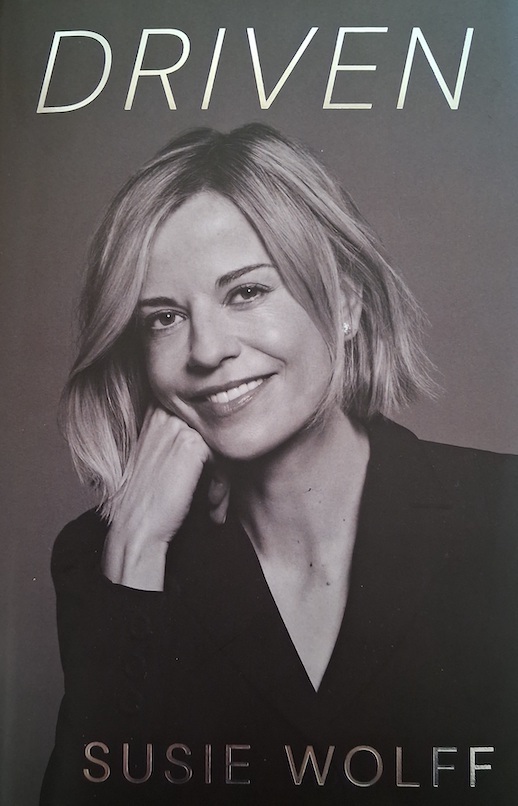

Driven

by Susie Wolff

“I was fighting to prove that talent mattered more than gender. I didn’t want special treatment—I wanted a level playing field. I wanted to win. On the same terms as everyone else.”

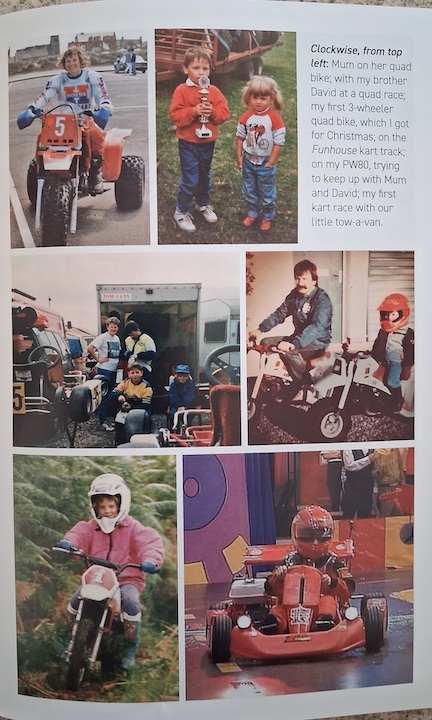

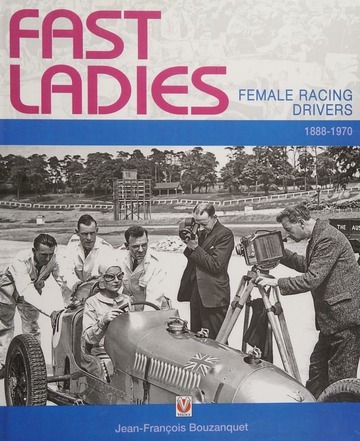

Despite Rod Stewart’s assertion, not every picture tells a story. But there are two pictures which have a lot to say—the studio portrait on the cover of this book and the photograph inside of the dumpy tomboy with the tragic hairdo in the godawful pink race suit. This is the story of how a gauche young Scottish karter was transformed into the confident, immaculately coiffed businesswoman called Susie Wolff.

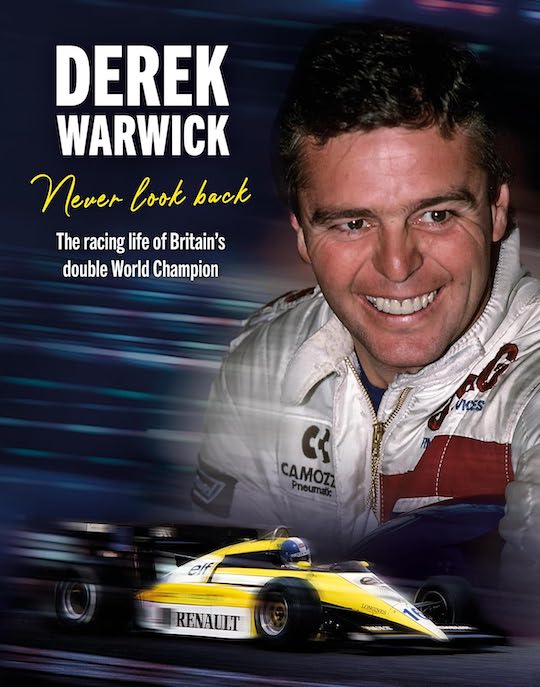

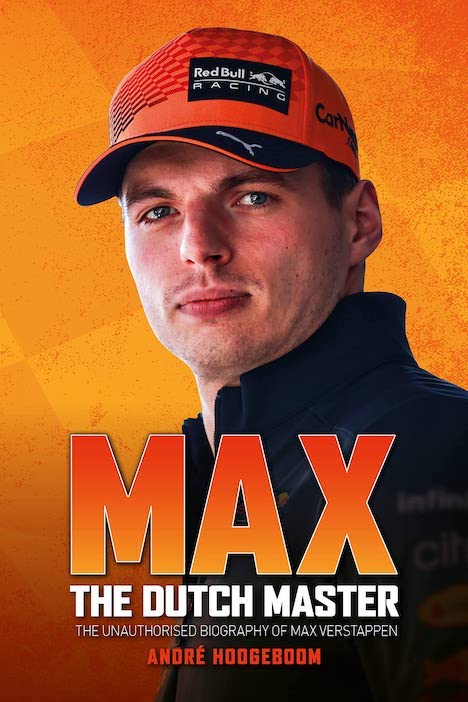

Williams F1 test.

I confess that my hopes weren’t high for this autobiography. I feared there’d be talk of her “journey” and about how self-belief can manifestsuccess, probably seasoned with ex post facto comments about “destiny”. But I shouldn’t have been so cynical because, with few reservations, this book—co-written by David Stoddart, Susie’s brother—is a fascinating and well written autobiography.

I first saw Suzanne Stoddart (b. 1982) race at my local circuit, in Formula Renault single seaters. Unlike Kimi Räikkönen and Lewis Hamilton (both winners at Croft in thesame formula), Susie was a mid-fielder but, women racers being rare, I remembered her name until she became a household one a decade later. Of course she had graduated from karting, a discipline largely off my radar, and I enjoyed reading about her early career, which had been made possible by coming from a family obsessed by motorsport. The fact that they came from Oban, on the west coast of Scotland and a very long drive from the nearest race circuit, was no disincentive. Nor was the fact that the family’s small business interests were barely sufficient to get their daughter on to the nursery slopes of motor sport.

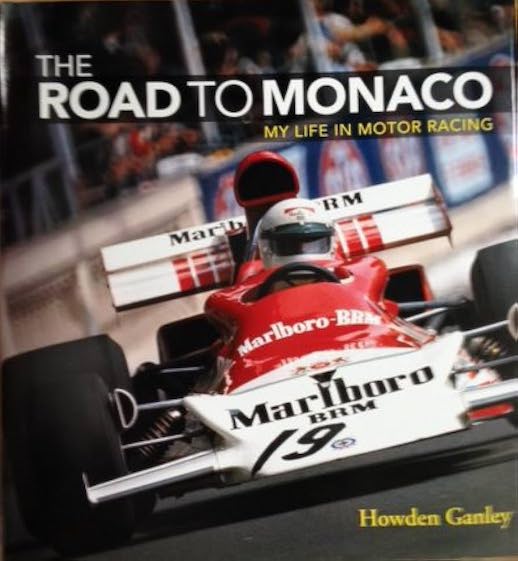

The account of how Susie ascended from British national karting, via the European Karting Championship and Formula Renault, to the DTM [1] consumes the greater part of the book, which is to its credit. Susie’s test outings with the Williams Formula One team earned her more press coverage than the rest of her career combined, but that reflects the fact that the non-specialist press only has eyes for the top rung. The reality was more prosaic—she was competent, professional and quick, but the chances of her securing an F1 race seat were tiny. As they were and still are for any young male driver, of whom there is a much bigger supply. The account of her F1 experience conveys both the pressure of the occasion and the physical and mental demands of driving a high-downforce single-seater, and we already know where that story ended. But there’s no disgrace in having only touched the hem of F1—just ask the legion of young Red Bull drivers. The Red Bull Academy has a class of thirteen as I write, in formulae from F2 to Ginettas, and thirteen will be the unlucky number for most, if not all, of them. (But maybe keep an eye on Fionn McLaughlin?)

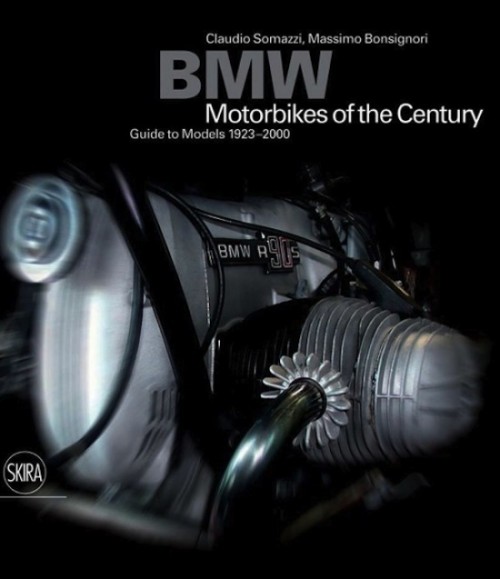

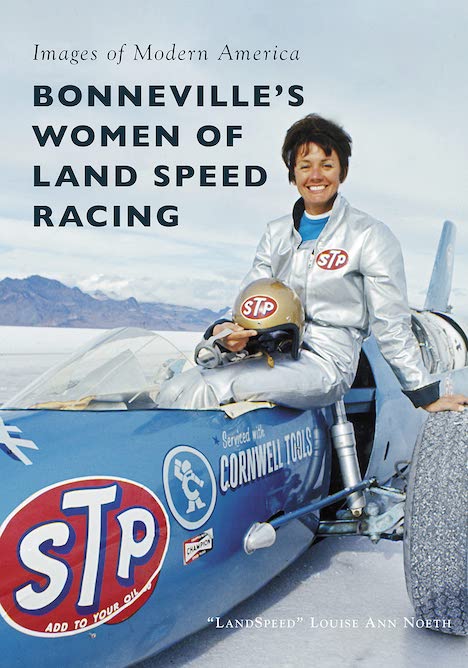

It is the transition of the kid from the sticks to the punchy young woman wrestling a DTM Mercedes around Hockenheim and the Norisring that makes this book so readable. We learn of the shock she experienced at racing with big boys, literally and metaphorically, in European Karting with the team run by Peter de Brujin and his formidable wife Lotta Hellberg. “Lotta didn’t exude warmth, and the bond I’d imagined—two women in a male-dominated world—didn’t materialise.” But the tough love approach worked in the rough and tumble karting world, as it needed to, given the two key challenges she started to face. She writes revealingly on both, the first of which was the sheer physical demands of racing in machinery (and even race kit) that made no concession to the difference physiology of women. Men of my age often sneer at the apparent ease a modern race car can be driven when compared to (sigh) the “‘real men’s cars” of our youth. The account of the brutal physical demands of racing a powerful, aero-heavy big race car convinced me I wouldn’t last five minutes in anything feistier than a superannuated Formula Vee.

You can guess the second challenge—sexism and its more toxic cousin, misogyny. As if having to race a pink Mercedes DTM car were not enough, Susie also endured comments like this one from Jean Alesi, “I told you to get this girl put of my way.” Or Niki Lauda’s advice to racer son Mathias, “The most important thing. Beat her.” In mitigation, some years later, Lauda apologised, “. . . I’m sorry. But I didn’t know you were going to be quick.” There is also an account of Susie’s own #MeToo moment, when she was pursued, after a Hugo Boss party, by “one of the most powerful men in F1 (who) could have had the ability to make or break my career.” Even though the man had tried to break into her hotel room, she later shook hands with him and comments, “I didn’t believe this man was a predator.” But I suspect many readers will.

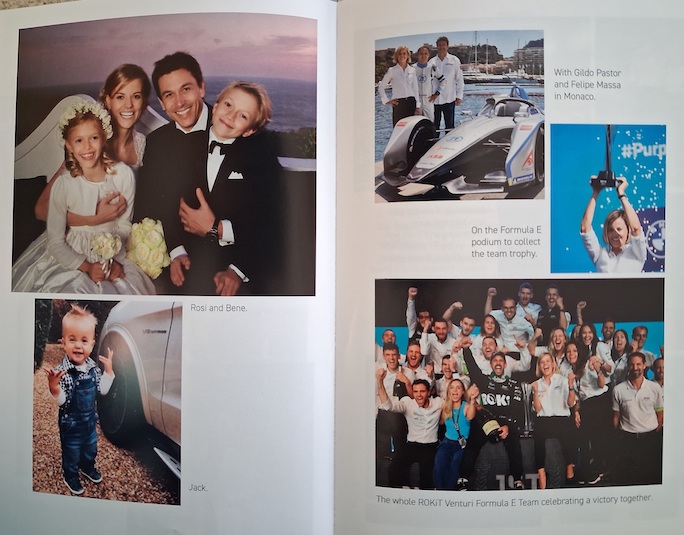

Family life and Formula E success.

I found the account of how Susie fell for Toto Wolff (and he for her) surprisingly touching, perhaps because her romantic life had hitherto sounded surprisingly sparse. We hear of a previous relationship with Thomas [2], the Audi DTM team manager, but it is clear the Wolff/Stoddart relationship was the real thing, proof of the coup de foudre Toto experienced on his first encounter. The story of how the Wolffs then became household names—Mercedes F1 domination, Venturi Formula E, F1 Academy—was already so familiar that most of it doesn’t make for especially interesting reading, nor offer much new perspective. The tone of the prose becomes slicker, with the language of the boardroom peppering the pages—due diligence, M&A [3] advisors, private equity, and an irony-free reference to “the family investment office” (like every normal family has, right?).

There is still some grit in the oyster though, and I enjoyed the account of how Susie took on the FIA after its ludicrously ill-founded accusation that a conflict of interest existed, simply because Susie was running the F1 Academy (for women racers) and Toto was the Mercedes F1 boss. The idiocy of the allegation was reflected in the fact that every Formula One team (who rarely can agree on the time of day) united in support behind her. The FIA was then (as it is now) under the leadership of Mohammed Ben Sulayem and I suggest any reader laboring under the misapprehension that FIA elections are transparent do a little googling about the latest stitch-up. But it is perhaps significant that Ben Sulayem isn’t even mentioned by name in the book. It looks like Susie has fallen as much in thrall to the Gulf States’ sport-washing as many of her peers have, expressing her sense of optimism that “change wasn’t happening overnight, but it was real and deliberate.” Real and deliberate?

Early days.

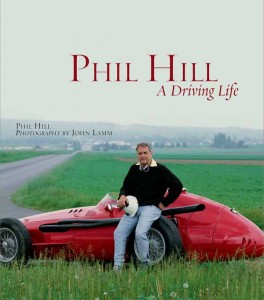

The book is written in a racy and accessible style, the editing is excellent, and my inner pedant was disappointed to find not a single error. The photos are small but well-chosen and the shots of Susie’s early career have an endearingly naïve charm.

There is neither index nor career appendix, and the book would have benefitted from both, especially because it is often difficult quickly to work out which year an incident took place (a fault shared by most books I’ve reviewed this year). But these minor cavils apart, Susie Wolff’s story is a good one which deserves a wider audience than the purely F1 demographic. And, now that Toto has reportedly sold his stake in the Mercedes F1 team for $300m, one suspects that there are many more chapters in the Wolff family history waiting to be written.

- DTM – Deutsche Tourenwagen Masters – German Touring Car Championship

- A few seconds’ googling will satisfy any curiosity about Thomas’ full identity

- M &A – Mergers and Acquisitions

Copyright 2025, John Aston (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter