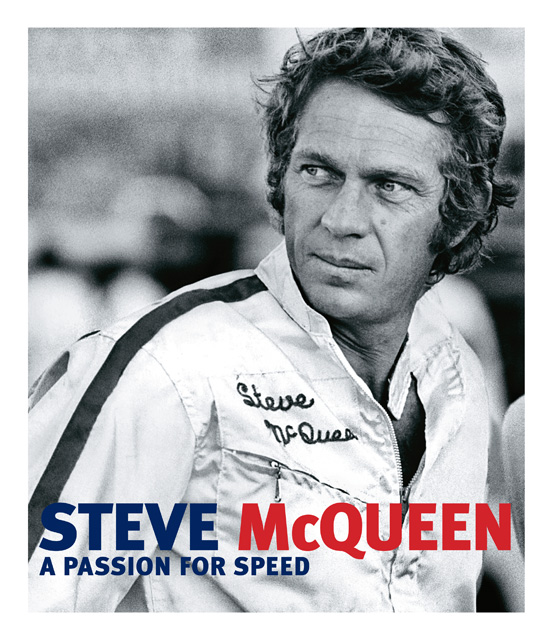

Steve McQueen: A Passion for Speed

by Frédéric Brun

by Frédéric Brun

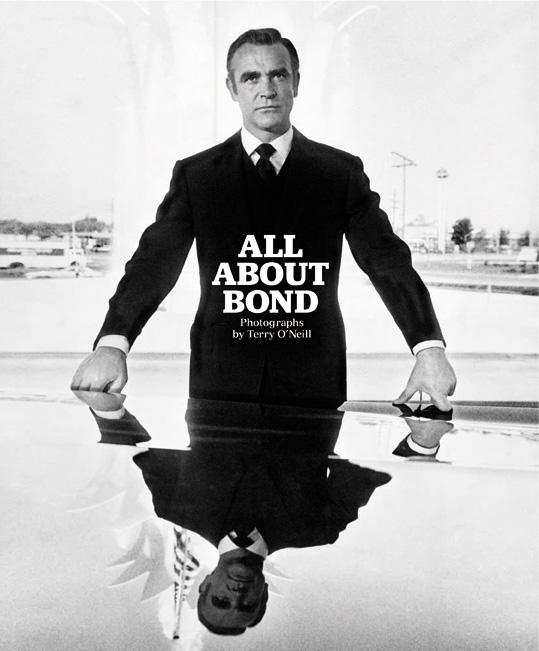

“I’m not sure whether I’m an actor who races or a racer who acts.”

To an American reader a book written from a foreigner’s perspective about a quintessential American icon is often as revealing as it is disconcerting—the two being different sides of the same coin. Different cultural reference points really do make for differently nuanced perspective and assessment.

This may sound needlessly complicated—and a book review is hardly the place to explore this notion—but it is relevant inasmuch as Brun, a Frenchman with a mind formed by different schooling, is able, for instance, to accept the considerable ambiguities in his protagonist without the need to explain them away or pretend they don’t exist. He shows us the McQueen who thinks of himself as “always a kind of a coward, constantly trying to prove myself” and the unapologetic “Up yours!” proverbial man’s man. Another example of this willingness to entertain seemingly contradictory ideas is Brun’s assessment of that most car-centric movie McQueen was involved with (as producer and star), Le Mans. In the space of one paragraph, Brun can call the movie—which was undeniably a commercial and critical flop—“barely watchable” in strictly cinematographic terms (c’mon, it is true; try watching that movie with someone who’s not into racing and see their eyes glaze over after a while) but also “one of the most stunning cinematic accounts of motor racing and the magic of competition and speed.”

Brun, it should be noted, is himself an amateur racer and his especial interests in film and in cars (he has published in both areas) gives his commentary a particular sensibility. Incidentally, the book jacket describes him as a “political attaché in the French Parliament” and it probably needs clarifying that this means a PR man/secretary “attached” to a Congressperson.

In his 11-page Introduction, Brun lays out a sympathetic picture of the sort of insecure personality that could keep a psychoanalyst busy for years, touching upon those aspects of McQueen’s childhood and private and professional life that are affected by his desire to “leave things behind”—by driving/riding/flying away from them or by drugs. The man you see through Brun’s eyes emerges as more conflicted, rougher, than you heretofore thought.

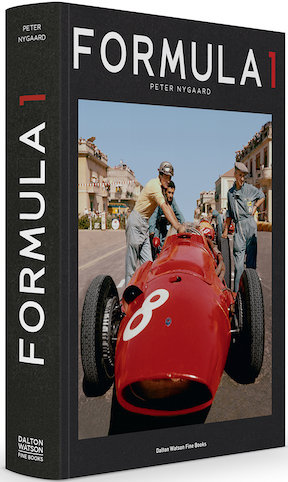

Without understanding Brun’s premise—that, no matter McQueen’s personal charisma, without the machinery with which he surrounded himself on screen and off “he would never have achieved such cult status”—it is too easy to dismiss this book as unbalanced. Instead it is a welcome addition (emphasis intentional) to other McQueen books, and aside from its fresh point of view introduces new photos to the record.

Even if you remove all of the psychological moments you’re still left with the fact that McQueen was a competent, keen driver who really could give accomplished amateurs a run for their money. The American Sports Car Association named him 1959 Rookie of the Year and, no matter his later fame, he considered that one of his proudest accomplishments.

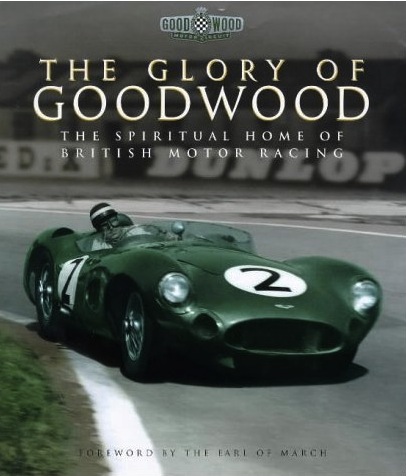

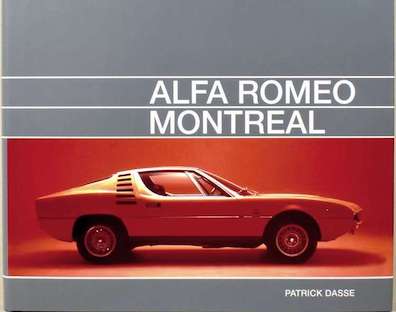

Brun’s story is divided into different aspects of McQueen’s life, beginning with his hubcap-stealing teenage days and ending with the posthumous sale at auction of many of his vehicles. Given Brun’s interest in film he ably draws attention to the conscious choices McQueen made for the sorts of machinery his and also the other characters would use in those movies that required mechanized transport (he was no stranger to horses but they’re not part of this story). There’s no point in enumerating here either the movies or the races in which McQueen took part save to say that everything that is relevant is covered in the book, in good and engaging detail. Occasionally there is the sort of tidbit that has either been long forgotten or never actually been recorded yet, such as McQueen’s argument with the TAG Heuer chairman over something that today is indelibly associated with McQueen: the Heuer Monaco wristwatch.

Aside from the introductions to the five chapters, the story is mainly advanced in the form of photos. Not all them are captioned and some audience participation will be required of those who really want to know what goes with what. There’s not much new among the film and car/bike photos (no aircraft are shown except for the glider in The Thomas Crown Affair) but on the personal front there is quite a number of candid and previously unpublished photos. All the photos are splendidly well reproduced on matte paper (photo credits are listed at the back in, for once, a really easy-on-the-eyes format). Cars and bikes are correctly described, one exception being the Rolls-Royce in Thomas Crown that is here—as in most other books—wrongly called a Silver Shadow coupe. There is no such thing; it is a Mulliner Park Ward coupe, later to become the Corniche.

The well-chosen photos reveal much about McQueen and it’ll be your loss if you rush through them. Another thing worth savoring are the book’s low-key but meaningful design elements. Example: chapters open on a recto [right] page; the opposite, verso [left] page shows the chapter title in mirror image—sort of a clever rearview mirror/coming & going effect. Surely no accident. No Index.

Originally published, also in 2011, in French as Steve McQueen: une passion pour la vitesse. That the English version reads so well is in no small measure thanks to British translator (trilingual!) and French resident Flo[rence] Brutton who didn’t just slavishly translate but discerned the essence of the French text and then recast it in proper English.

Copyright 2011, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter