Wheels of Her Own, American Women and the Automobile 1893–1929

by Carla R. Lesh

by Carla R. Lesh

Two books published and released very nearly simultaneously addressed the relationship between women and cars. But the similarities ended at that point for this book focused on the 1893–1929 timeframe and the other explores that relationship in more current times “from vintage muscle cars to electric vehicles.” We’ll tell you about the latter one in a subsequent commentary.

Working as the collections manager and digital archivist of a maritime museum gave Carla Lesh the skills she put to good use researching and writing this book. Her interest and thus inspiration had been hearing her grandmother, to whom she dedicated this, her first book, tell stories “of the early automotive era.”

That said the title chosen, Wheels of Her Own, American Women and the Automobile, 1893–1929, doesn’t really convey the book’s content for Lesh has written of far more than just women. It really is an exploration of how the emerging, earliest automobiles effected and influenced the lives of three groups of minorities—White, Black, and Indigenous. So White women, yes, but Blacks and Indigenous peoples of both sexes are told of in this far-ranging survey of life as experienced during the timeframe of the title for each of the three groups are written about in equal measure in each of the six chapters.

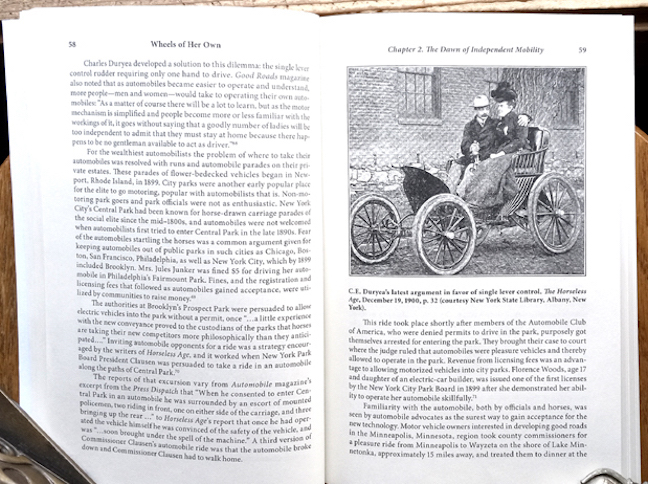

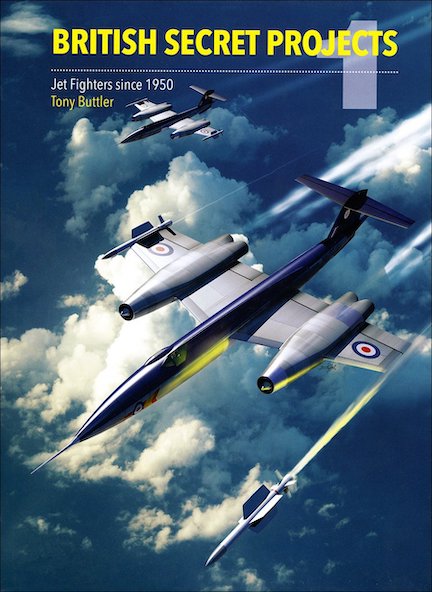

At first glance, an innocent and innocuous image. But look again as the image was used to publicize the new-in-1900 “single lever control rudder requiring only one hand to drive” thus, sigh, permitting the driver to pay more attention to his passenger!

Over time Lesh searched numerous archival collections, read books and period magazines, and found other sources as detailed in the bibliography and chapter end notes. The material she found enabled her to write of the opportunities independent mobility of the automobile opened up for “whoever took the wheel, as well as the harms of inequities to access, safety, good lodging and fuel, and reliable equipment,” not to mention the lack of well-marked, much less paved roadways except in and around well-populated areas.

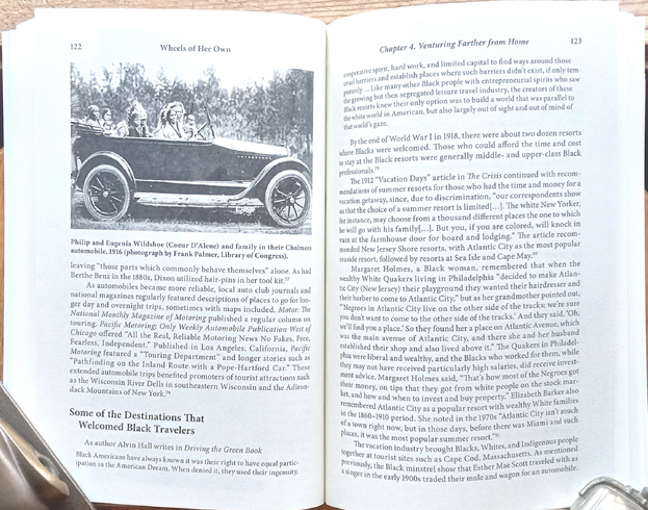

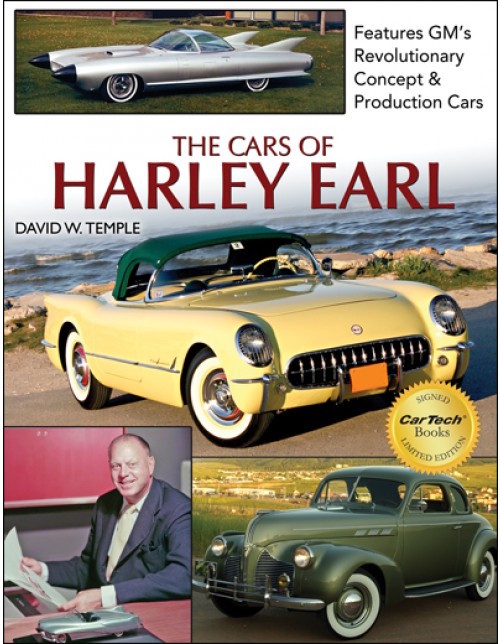

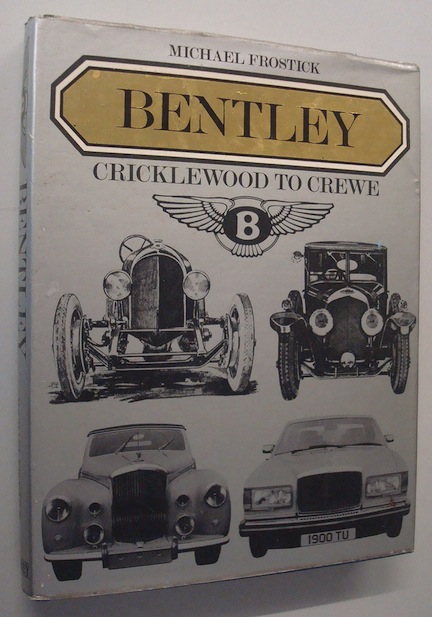

Indigenous people, Philip and Eugenia Wildshoe of the Coeur D’Alene tribe, shown putting their Chalmers to good use transporting the entire family in this 1916 image that is also on the book’s cover.

You know how with some books it seems to take a few pages for the reader to “get acquainted” with the author’s style and ways of sharing the information? Such was the case for your commentator with this book mostly because that title clearly hadn’t prepared me for all that would be covered. As an example, Lesh writes in her “Introduction: Our Itinerary” that in the first chapter “We look at the various modes of transportation with which women were familiar.” Thus, as I read that first chapter it took me by surprise (in a good way) to find a subhead in the chapter of “Differences Along Racial Divides” followed by eight pages of discussion. Following that was another six pages discussing the subhead “Indigenous Women’s Travel.”

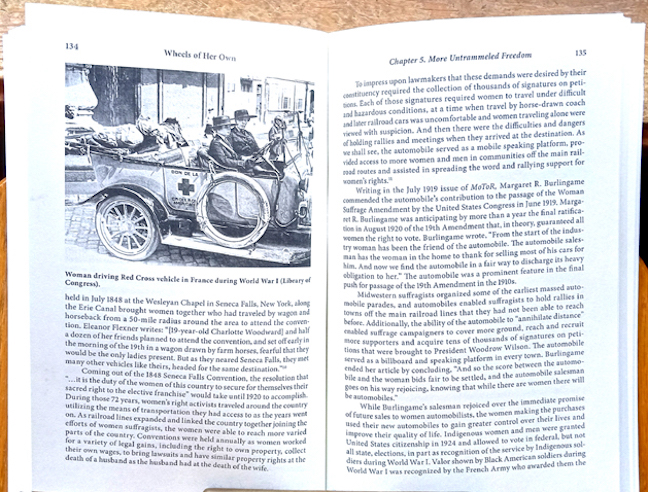

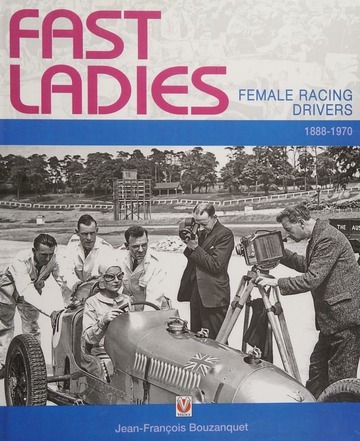

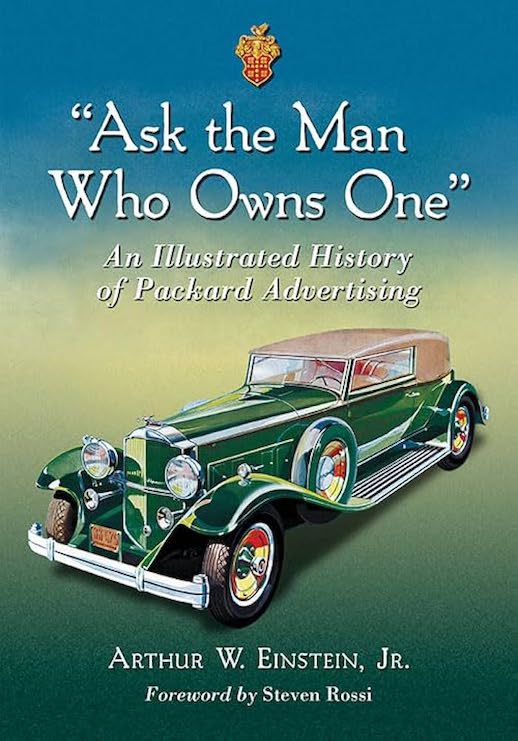

Women drove Red Cross vehicles during World War I as shown in this image taken in France. It illustrates the fifth and next to last chapter titled “More Untrammeled Freedom.” A multiple-page section of the same chapter addresses “Packing for the Long-Distance Drive” that will provide readers any number of chuckles.

From that point on I just let the far-ranging vignettes of information carry me along. In the third chapter Lesh introduces Chicagoan Charles Reese who rose from chauffeur and conducting classes to train others in the profession at the YMCA to owning his own school and training innumerable others to the trade. In those days being a chauffeur meant having skills other than behind the wheel for a true chauffeur was expected to have sufficient mechanical knowledge to maintain the vehicles in his charge in top mechanical condition as well as keeping them always clean and presentable, inside and out. And whereas at the Y he had been permitted to train only Whites, with his own school which he established in 1916 a person’s age, sex, or race made no difference. By 1923 his school was so successful it grew to include an auto repair shop, garaging, and sales as well. In case you haven’t guessed, Mr. Reese was a Black man.

If you’re unfamiliar with a lady named Zora Neale Hurston (I was unaware of her until reading this book), take the time to look up this incredible lady and an achiever in so many fields of endeavor. Or acquire a copy of this book to read about Hurston and all who Lesh discovered and has written of in Wheels of Her Own.

Copyright 2024 Helen V Hutchings (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter