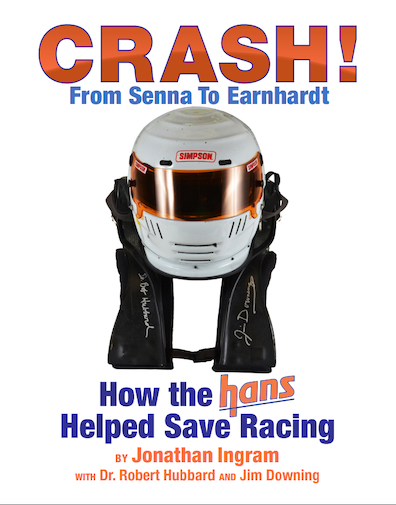

Crash! From Senna To Earnhardt

How The Hans Helped Save Racing

with Dr. Robert Hubbard and Jim Downing

“After Clark’s death there was concern the sport would be outlawed due to the obvious lack of safety represented by the fatal crash of its greatest driver. But the absence of scale when it came to motor racing’s popularity and the lack of broad commercial involvement precluded any great backlash. . . . The death of Senna, whose estate was valued by some as high as $400 million, occurred on the opposite end of the spectrum when commercialization was in full bloom. His crash in a car powered by Renault and sponsored by the Rothmans International tobacco company was beamed into homes, bars, motor homes and public houses globally, the same medium that had made the Brazilian driver a leading light in the daily march of sports heroes across TV screens everywhere.”

People say modern racecars, even at staggering speeds, corner as if they’re on rails. And they do. If everything goes right. Downforce, baby. When it is disturbed or interrupted, even for a moment, the car becomes unstable, possibly unrecoverable.

High cornering speeds were a common factor in the nine deaths across all the major series—F1, IRL, CART, NASCAR, NHRA—between 1994 (Ratzenberger, Senna) and 2001 (Earnhardt) but any kind of sudden deceleration or impact creates forces that need to be dissipated beningly. For the engineer it’s an easy enough principle to understand but for too long the sport that prides itself on being on the cutting edge of technology remained unfathomably cavalier about enforcing/mandating driver safety. Mind you, the drivers themselves were not all on board, no matter what the science said: Earnhardt, for instance, resisted using the HANS device even though three fellow NASCAR drivers (Petty, Irwin, Roper) had already been killed from basal skull fractures just months before.

If an engineer had been in charge of designing the human anatomy, he would probably have flunked his class. That top-heavy skull atop a spindly spine is an accident waiting to happen. Evolution obviously favored this arrangement for our species, so human ingenuity could have at least devised a way of reinforcing/protecting that connection in those situations that really fall outside normal operational conditions. Enter pro racer and five-time road racing champion Jim Downing (b. 1942) who had himself had an almost fatal crash. He surely cannot have been the first man to think about the problem but he is credited with bringing three things to bear: to link cause and effect (unlike the seatbelted torso, in a sudden deceleration event the unrestrained head has no support), propose a solution (prevent the head from whipping fore and aft, but without depriving it of the movement required for operating the car), and bring in the man who could work out the science and spec the design. That was Dr. Robert Hubbard (1943), a biomechanical crash engineer and, conveniently, Downing’s brother-in-law. Their HANS device is the original and the most common but not the only one. That they are both involved with this book means that their side of the story is fully preserved, in Hubbard’s case just in time as he died the year this book came out.

A good place to start the book is at the very end, with the HANS timeline 1981–2012. It correlates the device’s development to racing regs (and other external factors)—but it almost makes its adoption, even universal acceptance appear inevitable when, in reality, it wasn’t at all. Ignorance is one thing, but it boggles the mind to see how despite the mounting body of evidence (and of, groan, bodies) the sport’s functionaries and participants continued to either accept injuries/fatalities as part of the sport or resist the adoption of a restraint system by inflating its downsides (cumbersome to use etc.; F1 drivers are described as being in “an ongoing revolt” against it until 2003—after Alonso’s neck, literally, was saved in the Brazilian GP!). The book works out all the angles; that it jumps around a bit is surely not for lack of writing craft—Ingram has decades of race reporting and several books under his belt—but that so many overlapping strands have to be followed (cf. different racing series). Also, the device itself went though several iterations and was/is subject to continued improvement. (A good graphic early on highlights its operating principles.)

It would be reasonable to say that the sort of person who’s interested in this sort of book would come from the engineering, the racing, or the medical side. Each would have quite different backgrounds and interests, and one book to serve them all would probably fail each in some way so this book makes the engineering angle the strongest one. But, really, anyone with interest in motorsports in general will find something here that advances their understanding and appreciation. Not least, the topic of accident investigations, in the context of tangled interests and allegiances, makes for sobering reading.

It is entirely coincidental that the publication of this book happened just prior to the release of a documentary film based on racing physician Steve Olvey’s memoir “RAPID RESPONSE: My inside story as a motor racing life-saver” first published in 2006 and again in 2019 with new text and an afterword by Dario Franchitti (Evro, ISBN 978-1-910505-39-7). You’ll also want to read Professor Sid Watkins’ 1997 book Life at the Limit, Triumph and Tragedy in Formula One (Macmillan, ISBN 978-0330351393).

It is entirely coincidental that the publication of this book happened just prior to the release of a documentary film based on racing physician Steve Olvey’s memoir “RAPID RESPONSE: My inside story as a motor racing life-saver” first published in 2006 and again in 2019 with new text and an afterword by Dario Franchitti (Evro, ISBN 978-1-910505-39-7). You’ll also want to read Professor Sid Watkins’ 1997 book Life at the Limit, Triumph and Tragedy in Formula One (Macmillan, ISBN 978-0330351393).

Bibliography (incl. scientific papers), index.

Copyright 2020, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Very enlightening review, Sabu.

Thank you.