Horten Ho 229

The Horten All-Wing Jet Fighter, Spirit of Thuringia

by Andrei I. Shepelev & Huib Ottens

by Andrei I. Shepelev & Huib Ottens

“While no wartime document is known to confirm any ‘stealth’ activities within the Luftwaffe, the Horten 229 can in any event be considered a precursor to the latest flying wing, the blended-wing-body and related developments, both military and civil—stealth or not. Thus, seventy years on, the Horten’s vision is still at the forefront of aeronautical progress.”

You’ve seen a plane fly; you’ve seen a bird fly. Only one of them has (needs?) a vertical tail. Why?

This question has been asked for a long time, long before the Horten brothers, and even though there are answers they remain on the fringes of accepted practice. So much so that Albion Bowers of the NASA Dryden Flight Research Center can say in his excellent Introduction: “This great revolutionary idea is one whose time has come. It is not recognized, even by some of today’s foremost authorities in aeronautical engineering.”

There is no shortage of books on the Hortens, and flying wings in general but this one is especially good. Which is probably why it keeps getting reissued. First written in Russian,  with an insert in English, in 2002 by Shepelev (who wrote another one on the Ho 299) it was adapted into a stand-alone English version in 2006 (as number 12 in the well-known “Luftwaffe Classic” series by Classic Publications, an imprint of then Ian Allan and now Crecy) and reprinted 2014 and ’15.

with an insert in English, in 2002 by Shepelev (who wrote another one on the Ho 299) it was adapted into a stand-alone English version in 2006 (as number 12 in the well-known “Luftwaffe Classic” series by Classic Publications, an imprint of then Ian Allan and now Crecy) and reprinted 2014 and ’15.

Although the book is short at only 128 pages it dispenses high-grade and well-researched material at several levels and has something to offer the general-interest aviation historian, the wing specialist, and the modeler.

The first 10 pages are a veritable primer on first principles; read them and you’ll never not look at an aircraft again without admiration! There is no Glossary and this first part may well make the novice reader nervous because it is brimming with highly technical and specific jargon (a random sample from p. 9: “Various design combinations of both reflexed airfoil and twist are possible. The upward-bent trailing edge of the reflexed-airfoil wing and the outer sections of the twisted and swept wing are analogous to a tail in that they create, in a level flight, a nose-up balancing force to trim the nose-down momentum of the lift force of the wing.”)—but it eases up as the broader topic unfolds and is told against the backdrop of an action-packed few years. This one sample sentence is a good example of the clarity of thought and, yes, dramatic, carefully orchestrated prose to be found throughout which is all the more remarkable as neither author is a native English speaker (Ottens is Dutch).

If the drama of the language isn’t doing anything for you realize that there is plenty of drama in the actual events. The book paints a nicely rounded picture of the Horten brothers’ drive and ingenuity—in the face of only rudimentary formal training—and the difficult political and logistical conditions. Consider that they were only in their twenties went they cobbled together their first flying wing in their parents’ garage with hand tools. It took them 1000 hours to build and they got to fly it for only 7—everything they learned that made their aircraft better or at least different from the last one came from that limited stick time and pencil-and-paper exercises. How they managed to create a dozen different designs that way is a staggering achievement.

Something the book only deals with in passing because it is peripheral to its main purpose are the postwar Allied activities to either destroy or recover German technical projects. The US alone had several Technical Intelligence services attached to various branches of the military and this is very much case of one hand not knowing what the other is doing. Piles of books deserve to be written about just that!

Clearly, and this brings us back to where the review started, the Horten’s work was not really understood and so it is that Reimar Horten would only hit upon key solutions while he was in exile in Argentina frittering away his talent in obscurity. Yes, the flying wing we have today and those that are bound to come, owe something to the Hortens’ gliders and powered wings of which the Ho 229 was their most ambitious project.

New bits in this book are

- photographic proof that the sole surving Ho 229 was indeed assembled in the USA after the war

- reasons behind the extraordinary thick nose section of the wing and why there’s a sawdust layer in the wing

- the origin of the bat-tail on the later Horten flying wings

- postwar whereabouts of Horten flying wings

- extremely detailed drawings of all the Ho 229 versions by renowned artist Arthur Bentley

- first-hand information from Horten associate Karl Nickel (who wrote the Foreword) and his wife, the sister of Reimar and Walter Horten

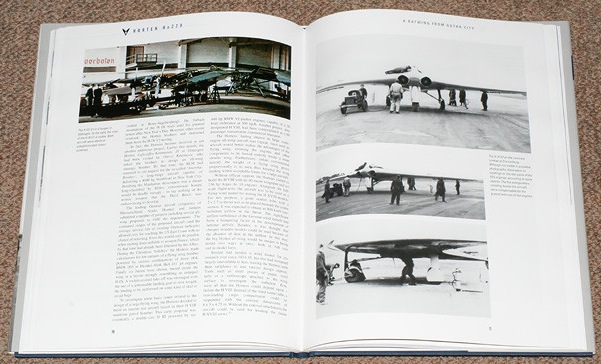

The vast number of really good photos are a delight as are the dozen pages of highly detailed 3-vies, cutaways, and other technical drawings. A short color section shows the survivor but it is no longer in Maryland as stated; it is at the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, VA, for a restoration to static display and may be visible at times.

Appended are a comparative (to other contemporary German jets) weight and performance table, specs of all Horton flyers, and End Notes. Bibliography, Sources, and index are all short but to the point.

Copyright 2016, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter