Canadian Art: The Thomson Collection at the Art Gallery of Ontario

A personal anecdote: Years ago, a book of paintings of the Canadian artist Alex Colville dropped into my lap, and my appreciation and interest for this painter has remained undiminished. Upon discovering that a good number of his works were on display at the National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, I undertook a special road trip just to see Colville’s work firsthand. The trip was wonderful, the National Gallery was wonderful, but, at the time of my visit, only two of Colville works were on display, the rest in storage. But all such encounters usually end in pleasure—at the museum I encountered a world of Canadian artwork that had been hitherto unknown to me. And it is not surprising that all of the artists featured in Canadian Art are represented at the National Gallery; these are artists obviously well respected in their homeland. After reading this book and falling under its spell, I will make another visit up north, this time concentrating on The Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) to see the artwork that this book has brought to my attention.

Canadian Art catalogs and explicates the collection of Kenneth Roy Thomson (1923–2006), 2nd Baron Thomson of Fleet, who, at his death, was the wealthiest person in Canada. In 1953 he began “seriously collecting,” and eventually he donated the collection to the AGO. Working along with Frank Gehry, the architect, and Matthew Teitelbaum, the director of the AGO, Thomson’s goal was to exhibit the art in such an atmosphere that museum visitors would “feel at home.” The first chapter of the book examines nineteenth century masks, amulets, rattles and walking sticks fashioned by the artists of the First Nations of the Canadian northwest coast. The intricacy, the design, and the power of these objects inspire admiration and reverence; the abstractions of animal and natural forms are beautifully and delicately carved, and the patina of old marine mammal ivory produces an abiding, substantive effect. A significant example is the Tlingit shaman’s amulet: Twin bear heads of ivory frame a small, grinning octopus with its formularized rows of suctions cups; the eyes of the bears are shells of the abalone.

Canadian Art catalogs and explicates the collection of Kenneth Roy Thomson (1923–2006), 2nd Baron Thomson of Fleet, who, at his death, was the wealthiest person in Canada. In 1953 he began “seriously collecting,” and eventually he donated the collection to the AGO. Working along with Frank Gehry, the architect, and Matthew Teitelbaum, the director of the AGO, Thomson’s goal was to exhibit the art in such an atmosphere that museum visitors would “feel at home.” The first chapter of the book examines nineteenth century masks, amulets, rattles and walking sticks fashioned by the artists of the First Nations of the Canadian northwest coast. The intricacy, the design, and the power of these objects inspire admiration and reverence; the abstractions of animal and natural forms are beautifully and delicately carved, and the patina of old marine mammal ivory produces an abiding, substantive effect. A significant example is the Tlingit shaman’s amulet: Twin bear heads of ivory frame a small, grinning octopus with its formularized rows of suctions cups; the eyes of the bears are shells of the abalone.

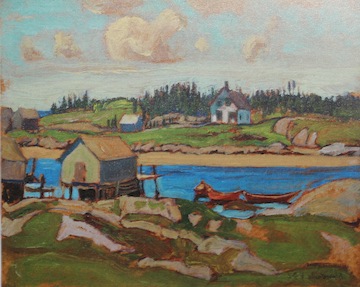

The subsequent chapters, one artist per chapter, focus on painting, and it has been said that a painting is not so much a representation and celebration of subject matter but rather a representation and celebration of light. Paintings from a particular region capture the characteristics of light of that region—even pure abstractions must be influenced by the ambiance of light in the artist’s studio. What color is the sky? How does a broad cloud shadow against a steep cliff shade the water below it? What happens to the color of ice when the sun is rapidly falling to the horizon? Cornelius Krieghoff (1815–1847) peoples his canvases in a manner reminiscent of Brugel the Elder’s work, but the skies above the houses capture the steel grey of a Canadian evening or the pure blue of an afternoon. James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924), from Montreal, first studied in Paris, and, throughout his career, he had painted scenes of the northern coast of France, and of Venice, Morocco, and Tangiers. Paintings from these travels are found in this chapter, but surely it is his Effet de neige (Québec) that is the most prized: Snow falls upon a roadway, houses and horse drawn sleighs, all against a backdrop of a sky of dark gunmetal.

The subsequent chapters, one artist per chapter, focus on painting, and it has been said that a painting is not so much a representation and celebration of subject matter but rather a representation and celebration of light. Paintings from a particular region capture the characteristics of light of that region—even pure abstractions must be influenced by the ambiance of light in the artist’s studio. What color is the sky? How does a broad cloud shadow against a steep cliff shade the water below it? What happens to the color of ice when the sun is rapidly falling to the horizon? Cornelius Krieghoff (1815–1847) peoples his canvases in a manner reminiscent of Brugel the Elder’s work, but the skies above the houses capture the steel grey of a Canadian evening or the pure blue of an afternoon. James Wilson Morrice (1865–1924), from Montreal, first studied in Paris, and, throughout his career, he had painted scenes of the northern coast of France, and of Venice, Morocco, and Tangiers. Paintings from these travels are found in this chapter, but surely it is his Effet de neige (Québec) that is the most prized: Snow falls upon a roadway, houses and horse drawn sleighs, all against a backdrop of a sky of dark gunmetal.

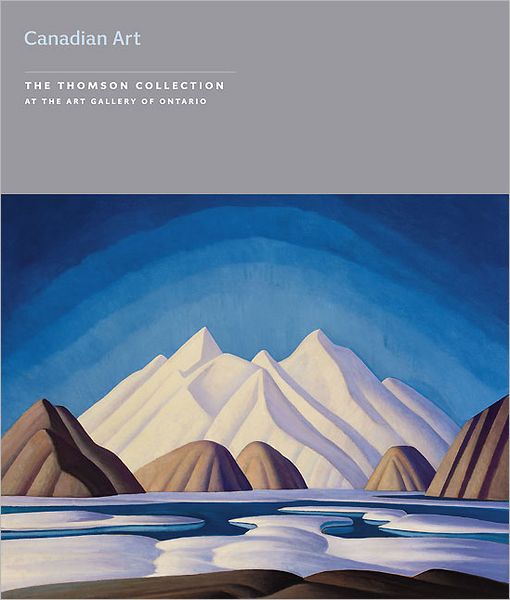

Although much more abstract than Krieghoff and Morrice, the works of David B. Milne (1882–1953), with their expanses of white and dabs of raw reds, yellows and blues, reflect the light of a winter sun, and in some paintings the raw canvas shows through, grounding and shadowing the layers of snow. For one series of paintings, Riches, the Flooded Shaft among them, Milne switches the background from white to black, to underscore the nearly toxic colors found in an abandoned, flooded mine. He writes to a friend: “To the miner it may be a disappointment but to the painter in search of color it is a find.” Lawren Stewart Harris (1885–1970) follows, taking abstraction to transcendental heights. His earlier work is similar to the preceding painters, but by the mid-1920s, his mountains become stylized and monumental, and his skies, infinitely blue, are filled with shafts of divine sunlight, all of this a manifestation of Harris’s dedication to Theosophy. If one viewing these later works were in the right state of mind, the experience would surely be transformative. One from this series, Baffin Island Mountains, is used for the cover of the book.

Although much more abstract than Krieghoff and Morrice, the works of David B. Milne (1882–1953), with their expanses of white and dabs of raw reds, yellows and blues, reflect the light of a winter sun, and in some paintings the raw canvas shows through, grounding and shadowing the layers of snow. For one series of paintings, Riches, the Flooded Shaft among them, Milne switches the background from white to black, to underscore the nearly toxic colors found in an abandoned, flooded mine. He writes to a friend: “To the miner it may be a disappointment but to the painter in search of color it is a find.” Lawren Stewart Harris (1885–1970) follows, taking abstraction to transcendental heights. His earlier work is similar to the preceding painters, but by the mid-1920s, his mountains become stylized and monumental, and his skies, infinitely blue, are filled with shafts of divine sunlight, all of this a manifestation of Harris’s dedication to Theosophy. If one viewing these later works were in the right state of mind, the experience would surely be transformative. One from this series, Baffin Island Mountains, is used for the cover of the book.

The next three artists, J.E.H McDonald (1873–1932), Tom Thomson (1877–1917), and F.H. Varley (1881–1969) offer similar works, mostly flora, fauna and pregnant woodland streams that show the influence of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements. The text discusses the excursions of these artists, going into the wilds of Canada, camping, absorbing the light in its various aspects, and recording their experiences with oils on canvas or wood. Paul-Émile Borduas, on the other hand, delivers non-representational canvases, done with thick impasto applied with the pallet knife, but even here the Canadian light is felt. Comparing, for example, his Le Chant des libellules with Milne’s Woman in Brown II, the evolution from stylized representation to pure abstraction is easy to absorb. In the last chapter, the paintings and the mixed-media works of William Kurelek (1927–1977) exude a pronounced strangeness in religiosity and allusions to the mental problems that had plagued him. Generally his canvases feel confined and personal, but an exception, his Don Valley on a Grey Day, realizes an aura of peace and temperance—reminding one of the semi-abstract landscape paintings of the California artist Richard Diebenkorn. It is a detail of Don Valley that is employed as full-page illustration to open this chapter. Similar full-page images are used for each chapter, and this device works well.

The next three artists, J.E.H McDonald (1873–1932), Tom Thomson (1877–1917), and F.H. Varley (1881–1969) offer similar works, mostly flora, fauna and pregnant woodland streams that show the influence of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist movements. The text discusses the excursions of these artists, going into the wilds of Canada, camping, absorbing the light in its various aspects, and recording their experiences with oils on canvas or wood. Paul-Émile Borduas, on the other hand, delivers non-representational canvases, done with thick impasto applied with the pallet knife, but even here the Canadian light is felt. Comparing, for example, his Le Chant des libellules with Milne’s Woman in Brown II, the evolution from stylized representation to pure abstraction is easy to absorb. In the last chapter, the paintings and the mixed-media works of William Kurelek (1927–1977) exude a pronounced strangeness in religiosity and allusions to the mental problems that had plagued him. Generally his canvases feel confined and personal, but an exception, his Don Valley on a Grey Day, realizes an aura of peace and temperance—reminding one of the semi-abstract landscape paintings of the California artist Richard Diebenkorn. It is a detail of Don Valley that is employed as full-page illustration to open this chapter. Similar full-page images are used for each chapter, and this device works well.

Canadian Art is an attractive book, having a light, airy feel as the pages generously incorporate white space into the design. Each chapter includes an essay written by a seasoned expert that describes the history and reputation of the artwork and the artist/s, and these, eschewing abstruse critical theory, are accessible to the general reader. A list for selected reading follows each essay. The introductory material includes a brief overview of the collector Thomson and a heartfelt reminiscence of him by his son David. I was surprised to see that the book is not indexed, although a brief vita of each contributor is given. I see Canadian Art as a gilt-edged invitation, an invitation to visit Canada—to visit her wilderness, to visit her exhilarating cities, and, particularly, to visit the AGO.

We began with an anecdote and will end with one, this one from Ken Thomson himself in a 1997 conversation with the AGO director who asked what makes a good collector: “. . . All good objects enjoy each other’s company and live together. You can have an object from the 16th century or whatever, and place it beside a superb 19th-century Netsuke. The materials are different, the subjects are different, but the quality is common between them. These objects can live together if they are beautiful, if each one is of wonderful quality, exquisite workmanship.” His collection embodied that and was highly personal, ranging from tiny ship models to a monumental Flemish Baroque painting by Peter Paul Rubens (Massacre of the Innocents c. 1611–1612). The book we reviewed here is only one of five published on the occasion of the unveiling of the AGO exhibit. They are available as a boxed set for $185 or individually.

Copyright 2013, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter