Soviet and Russian Ekranoplans

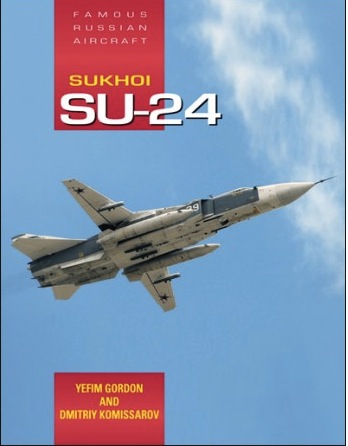

Sergey Komissarov & Yefim Gordon

Sergey Komissarov & Yefim Gordon

“In practice, the economic efficiency of WIG craft has not yet established itself as something indisputable. One of the factors affecting it is the relatively low payload to all-up weight ratio of the WIG vehicles built to date (due to the use of shipbuilding, rather than aircraft technologies in construction and to the necessity to carry as dead weight the booster engines which are only required at take-off).”

Ekranoplan~ Ekranoplan~ Ekranoplan. C’mon, it is a funny word to say! Never heard of one? How about a WIG craft? In simple terms, ships with wings.

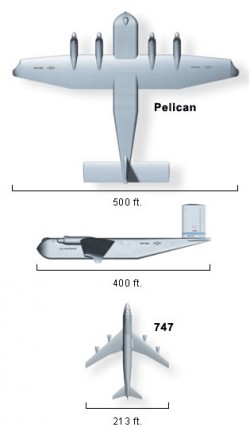

Imagine: there you are on your boat, daydreaming, and you have that sense that the air around just doesn’t feel normal. You look up—and skimming 30 ft above the water, a machine with a wingspan more than twice that of a 747 (500 ft vs 213) comes at you trailing a gigantic spray of water. The Pelican ULTRA by Boeing Phantom Works would be the largest-ever wingship and a flight-ready prototype by 2015 was announced in 2002—but the project has either gone so dark or so dead that no one has heard of it since [1].

Imagine: there you are on your boat, daydreaming, and you have that sense that the air around just doesn’t feel normal. You look up—and skimming 30 ft above the water, a machine with a wingspan more than twice that of a 747 (500 ft vs 213) comes at you trailing a gigantic spray of water. The Pelican ULTRA by Boeing Phantom Works would be the largest-ever wingship and a flight-ready prototype by 2015 was announced in 2002—but the project has either gone so dark or so dead that no one has heard of it since [1].

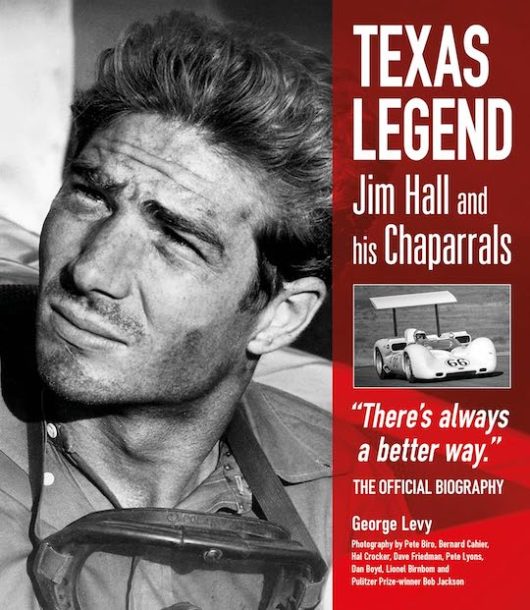

2002 is also the year one of the authors, Komissarov, penned what was then probably the best of the few books on wing-in-ground-effect (WIG) machines, Russia’s Ekranoplans: The Caspian Sea Monster and other WIGE Craft (ISBN 978-1857801460) as volume 8 in Midland Publishing’s “Red Star” series. The present book is a revised and in every way expanded version.

2002 is also the year one of the authors, Komissarov, penned what was then probably the best of the few books on wing-in-ground-effect (WIG) machines, Russia’s Ekranoplans: The Caspian Sea Monster and other WIGE Craft (ISBN 978-1857801460) as volume 8 in Midland Publishing’s “Red Star” series. The present book is a revised and in every way expanded version.

Ground Effect Vehicles have been studied since the 1920s in many countries but the Soviets owned that field by the 1960s and explored it continuously. Why them? They have the vast tracts of flat surfaces (water, ice, even land) that are essential for creating that cushion of air that results when either an engine blows against it or a something like a wing glides over it. If this sounds abstract, hold your hand near anything that emits a blast of air (hairdryer, vacuum cleaner etc.). The smaller the gap, the more resistance. Or the corollary: the better the cushion works the less power is needed to maintain the gap. You just simulated something akin to the aerodynamic principle of “lift.” And the less lift and drag fight each other, the more efficient flight becomes—ergo, WIG craft need to operate near to the ground to not lose the benefits of the air cushion. This makes the performance of the aforementioned Pelican all the more remarkable because over a land it could/can achieve a high altitude of 20,000 ft, making it, in Russian parlance, an Ekranolyot.

Together and individually the brothers Komissarov and Gordon have done a number of books together and decades of expertise under their belts. While history is never a predictor of the future, their track record is so strong that one is tempted to say that any book with their names on it is one you’d find enlightening. Certainly this one, which also seems to be a bit less lumbering in terms of writing style.

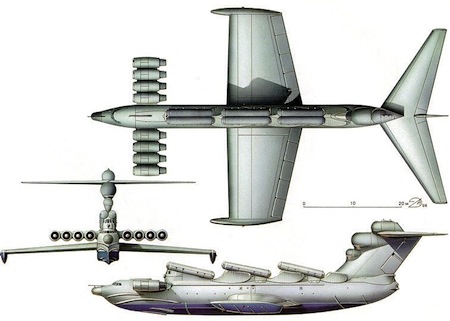

Beginning with a more scientific explanation than the above of aerodynamic forces and an overview of the nomenclature, the book makes clear that WIGs comprise a “wide variety of craft featuring substantial differences.” From aircraft carriers to space shuttle launchers to personal pleasure craft, some 50-odd military and civilian machines are presented. The book title doesn’t even hint at a special goody, the inclusion of a chapter on historical and present-day non-Russian efforts. There is also a chapter on, for lack of a better word, amateur efforts by privateers or university student groups that did theoretical or even practical work.

The bulk of the book describes one at a time the significant Soviet/Russian design offices or constructors, namely Alekseyev, Bartini, Beriyev, and Sukhoi. Befitting his place in aviation history, Alekseyev, head of the Central Hydrofoil Design Bureau, gets the most ink. Known for what the authors politely refer to as his “independent behavior,” it is nevertheless shocking to read how his detractors managed to get this genius of a man demoted in the wake of a 1975 accident [2] in which an unskilled pilot tore the tail off an CHDB ekranoplan. Never mind that Alekseyev, a passenger on the flight, saved everyone’s bacon and kept the craft moving long enough to make port. He died five years later, much too young at 64.

Individual designs are covered on several pages each, including a table of basic specs. An enormous quantity of thoroughly captioned b/w and color photos as well as technical drawings, 3-views, cutaways, profiles, and artist’s impressions (in the case of unbuilt machines) augment the text. Almost all the photos are very well reproduced but some of the drawings are plugged up and also have barely legible legends.

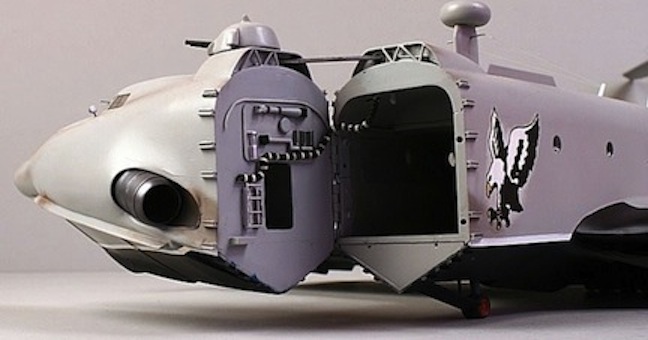

Kit modelers will be inspired by the many close-ups to enhance their builds but collectors of factory models will turn green with envy at the plethora of display models that are so impossibly hard to find (one photo alone shows at least forty different CHDB models on a table). And let’s not even talk about the ultra-rare working models used for wind tunnel and towing basin tests!

Doctor’s orders: pull out this excellent book at least once a week and marvel at what all is possible. And say “Ekranoplan” a few times in a row.

1 There was a US patent application in 2005/06 under the Pelican tag but for a differently-looking, smaller machine.

2 Take this date as a good example of why thinking that properly researched books could be substituted with Wikipedia is folly . . .

Copyright 2017, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter