Harley Earl

A book full of un-obvious and sensible thoughts, but . . .

Let’s begin where the author ends. Bayley, a design critic and former Director of the Design Museum, closes his book by saying “It is extraordinary that so little has been written about Harley Earl, America’s most influential designer. No doubt there will be later studies which will locate Earl more precisely in history and culture than this necessarily first loose shot.”

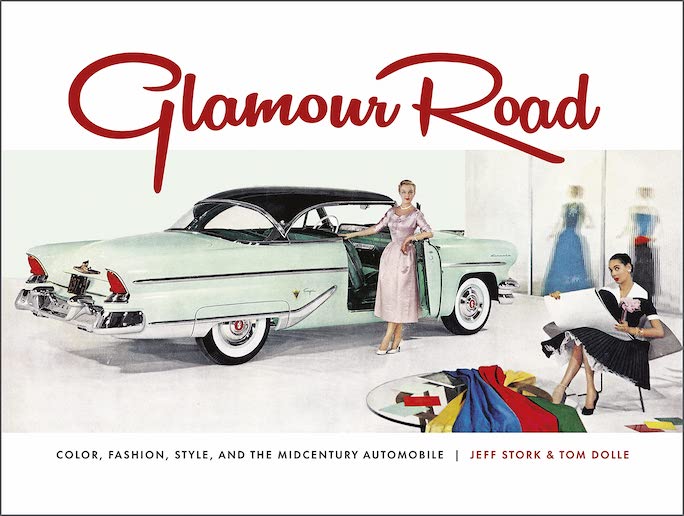

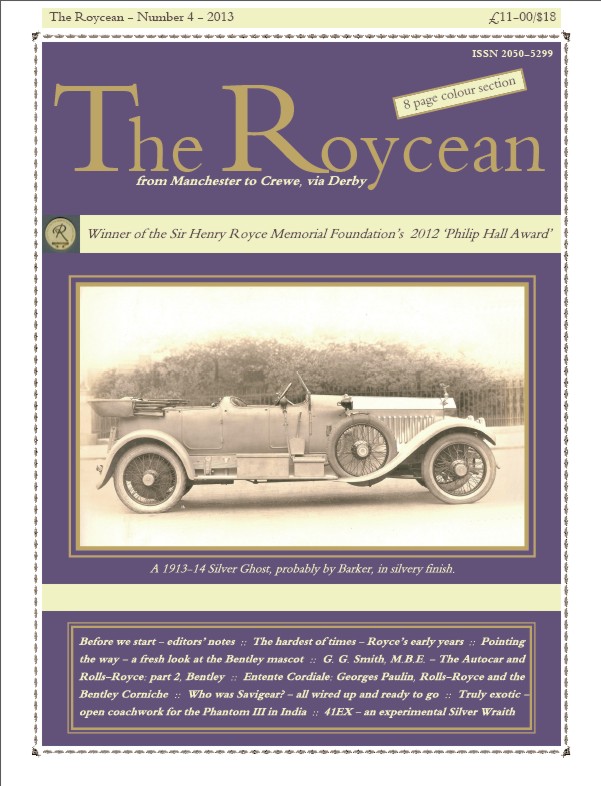

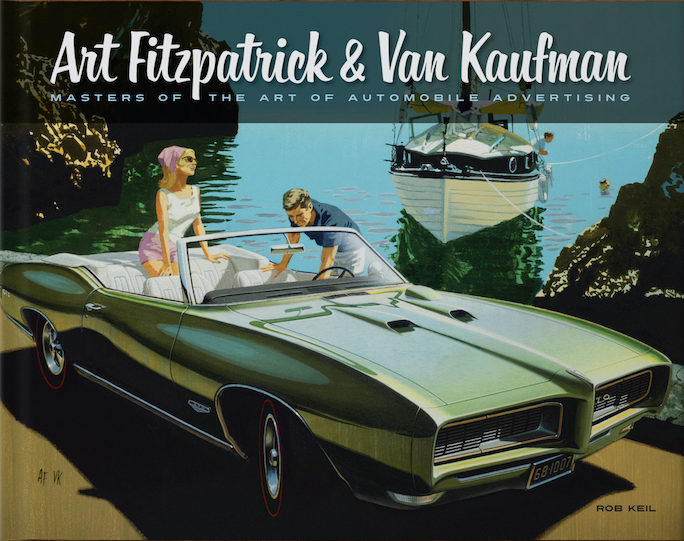

Harley EARL, you ask? He of the surrealistic finned chrome monsters?? The man whose flamboyant work even arch-conservative companies like Rolls-Royce paid attention to in the 1960s and to whose studios they routinely dispatched executives? (Motoring academics have, for instance, frequently suggested that the 1952 Bentley R Type Continental’s comely teardrop shape was “inspired by” the ‘49 Cadillac Series 62 Fastback.) Can it really be that little has been written about him? Yes indeed. And now we have book by a highly credentialed Brit—and therein lies trouble.

This small book takes a stab at a very large subject. Earl’s “bigger than life” demeanor ranged from his imposing physical size to the size of his creative vision. And that vision is what this book is about. It lays the groundwork by showing us Earl’s professional development at Hollywood’s Earl Automobile Works and then parades in front of us the cars GM designed under his aegis and relates his stylistic vocabulary to the context of their time. It also introduces us to his persona: Earl had a TEMPER. GM employees quaked in their boots when “Misterearl” stalked the corridors.

The photos are black and white only; clearly this book’s purpose is not to be another candied coffee table book oozing pictures of pretty cars. (Speaking of photos: the very last car photo is of the car that incurred The Wrath of Nader. It is regrettably mislabeled as a 1960 Impala, although the correct model is depicted, a 1960 Corvair. And speaking of unpleasantries: the proofreader clearly had a bad day. An occasional typo is forgiven but to have half a sentence printed twice fails to amuse.)

A look at the subtitle and the series editor’s preface enlighten us that this is one of four titles in Taplinger’s Heroes of the Design Century series (the other three are Sottsass, Fuller, Loewy). The Designer as agent of change—the Designer in the world and of the world—the Designer with ideas and personality big enough to change the way people see the word, interact with the world, forever change their expectations—the Designer as magician; as Superman. The Designer with a capital “D”.

Bayley contributes to a long string of newspapers and magazines, considers cars one of his passions, has written extensively on automobiles and automobile design, and judged anything from furniture to architecture to food at global design events. He and his publisher are British. Often it does take a “foreigner” to bring a wider perspective to bear. But sometimes, something seems to get lost in translation. While Bailey, based on his own design background, is perfectly able to explore, in a generic sense, the philosophical aspects of design, once cannot shake the impression that he is rather unsympathetic towards his subject in this instance.

The point should not be whether Earl’s work was good, or pretty, or necessary—but that it intersected with a moment in time in which a cultural and societal climate accorded design the power to effect far-reaching social change. More than speeches by politicians or displays of military might it is the chromed toasters, rocket-shaped vacuum cleaners, and, yes, finned cars made intellectual statements that influence history. Earl’s designs, the streamlining, the colors, the tail fins told the world something about America and Americans, their values and the place they claimed for themselves in the world order. On the flip side, GM’s prolific but stratified offerings codified a distinct class system.

And Bayley muses with considerable sensitivity on the “sorcerer’s apprentice” aspect of success. How Earl created an insatiable monster that fed on never-ending newness. The fact that it all fizzled out within three years of his retirement only serves to illustrate just how irreplaceable and forceful a personality Earl was.

It’s certainly a book that’ll make you think; but not all thoughts will be pleasant.

Copyright 2013, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

This book would seem to be a cheapened reissue of the text, at least, from the one Bayley first published in 1985, with higher production values:

http://www.amazon.com/Harley-Dream-Machine-Stephen-Bayley/dp/0394532449.

That his concluding sentence about it being just a “first, loose shot” still stands as valid nearly 30 years later suggests something worth noting. There would seem to be some obstacles standing in the way of worthy scholarship. Whether that’s academic disregard for the subject, General Motors, Earl’s heirs or something else, I’m not sure, but there’s something that explains the paucity of serious biography about such an influential figure.