Vintage Travel Guides

Navigation systems in cars are here to stay. They can be a real boon to getting where you need to go on time, especially in large European and American cities, with their labyrinths of one-way streets. But, for the less time constrained, there is another way of finding your way around new environs. True, it isn’t as quick and easy as plugging in your destination and then mindlessly following the synthesized voice of your mechanized navigator. However, it is more fun, more romantic and much more stylish to plan your motoring trips with the aid of vintage travel guides.

Navigation systems in cars are here to stay. They can be a real boon to getting where you need to go on time, especially in large European and American cities, with their labyrinths of one-way streets. But, for the less time constrained, there is another way of finding your way around new environs. True, it isn’t as quick and easy as plugging in your destination and then mindlessly following the synthesized voice of your mechanized navigator. However, it is more fun, more romantic and much more stylish to plan your motoring trips with the aid of vintage travel guides.

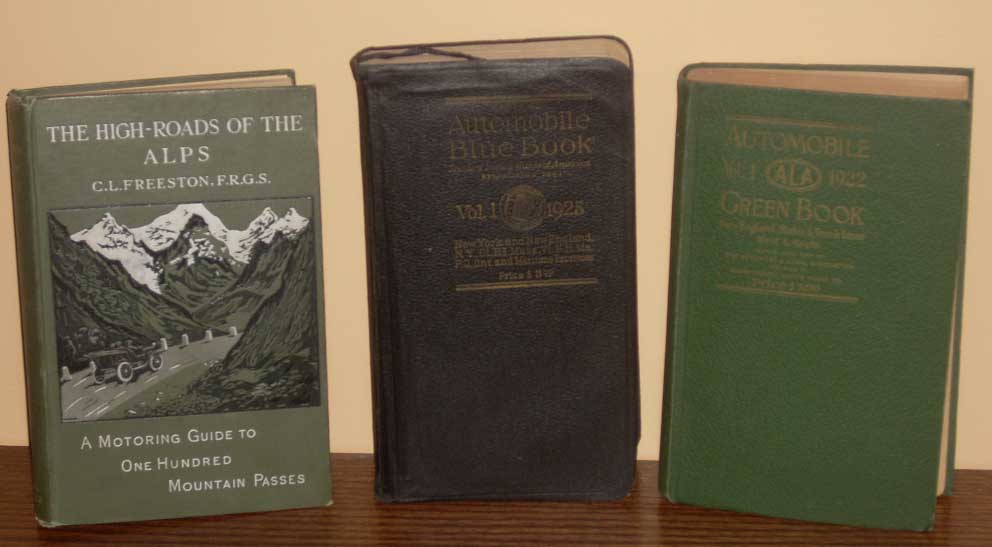

Motoring at the turn of the (previous) century was a real challenge. Vehicles were far from reliable, tires could be counted on to blow out regularly, and gasoline and oil were difficult to find for an automobilist who traveled far from home. Which made the motoring exploits of Charles L Freeston all the more remarkable. In 1910 he wrote The High-Roads of the Alps: A Motoring Guide to One Hundred Mountain Passes. The book represented the sum of 17-years experience motoring on the mountain roads of France, Switzerland, Italy, and the Austrian Tyrol. Imagine—17 years means he started his driving exploits during the 1800s. He followed his first book with The Passes of the Pyrenees in 1912, then later a series of books about continental motoring in the 1920s.

Freeston’s style is one of British upper crust, mixed with genuine optimism for driving over alpine passes, surely one of the most difficult undertakings an early motorist could imagine. Freeston writes, “The crossing of an Alpine pass is, beyond all fear of contradiction, the most interesting, the most sporting, and the most exhilarating purpose to which an automobilist can devote his car. All these varying sensations, too, of which the mind receives the imprint on the upward journey are intensified anew as they are experienced in the inverse ratio on the descent to the plains on the other side of the pass, while yet further variety is added by the contrast between the pastoral charms of the Swiss or Tyrolese valleys on one side and the smiling opulence of the Lombardy plains. The mountaineer is welcome to his extra thousands of feet; but no one can truthfully aver that nature as viewed from the roads themselves is not wondrously impressive and magnificently beautiful.”

Aside from the quaint style of writing, Freeston’s guides are still very valid today. The maps included in his books are accurate, as are his sketches of areas where two or more roads may be available. His photographs are beautifully reproduced and especially interesting when he includes views of his faithful Sheffield-Simplex or Daimler motorcar climbing the major grades.

A few years ago, I had a chance to use Freeston’s High-Roads of the Alpsduring a drive from Lyon in France to just outside Milan in Italy. Freeston devotes 16 pages to this route and includes a hand-drawn map and five photographs. He also includes this sage advice: “Happy-go-lucky methods never pay in touring, and, when mountains have to be crossed, are even dangerous; the man who thoroughly enjoys himself awheel is one who masters his available facts beforehand, and, so far from this policy interfering with his freedom of action, it enlarges it to the greatest possible degree.”

Armed with my 1910 guide, and the torque and horsepower from the inspiring engine of my press car, a Ferrari 355 F1, I felt the master of my destiny. Leaving Grenoble, the route climbs along several smaller rivers before entering a 600-foot tunnel and meeting up with the Infernet River. Let me tell you about the tunnel. I entered that first tunnel loafing along in fourth gear. Two hits to the paddle-shifter and the sound of the whooping Ferrari filled the passage with enough noise to bring down the mountain. It was glorious.

As Freeston details the locations of each tunnel and waterfall along the route, my drive soon became a series of aural and visual overloads. Remarkably, aside from paving the road, little had changed from that day in early July 1908 when Freeston came this way in a 45-horsepower Sheffield-Simplex motor car.

I stopped for lunch in La Grave, in the shadow of La Meije, a 13,000-foot mountain that dominates the scenery. Freeston describes La Grave. “Of La Grave it may be said that it occupies the most attractive position of any French village outside the region of the Mont Blanc range. It stands at 5,000 or so feet in altitude, which, if I may proffer an opinion, offers in almost every Alpine district the finest combination of picturesqueness, pure air that is not too rarefied, beautiful wild flowers, and an amplitude of excursions. It may only be personal preference, but looking back on the hundreds of towns and villages which I have visited in one district or another of the Alps, La Grave, though far less known to English tourists that the more popular Swiss resorts, is well qualified to occupy a place in one’s list of specially memorable spots.” True in 1908. True today.

Unfortunately Freeston never produced a motoring guide for North America. But that doesn’t mean that good automotive guidebooks don’t exist for American drivers. The Automobile Green Book, the official Tour Book of the Automobile Legal Association and the Automobile Blue Book, the Standard Touring Guide of America are two examples of books the well-equipped motorist would use in the 1920s. These books tend to be more terse and businesslike in their route descriptions, giving exact instructions how to journey from town to town.

I have occasionally used my 1922 Green Book to travel on back roads in New York and New England. It is somewhat harder to follow 70-year-old route instructions in the US than it is in Europe. America’s road network, befitting the younger nation, changed at a faster pace than those in Europe. But invariably a landmark will crop up allowing progress to be made. Not the best way to get across town in a hurry, perhaps, but a fun way to spend a nice drive early on a Sunday morning. Best of all, you can spend hours plotting future trips and studying early motoring, hotel, and restaurant advertisements in the Blue and Green guidebooks.

Finding old guidebooks is surprisingly easy. Used bookstores usually have a small selection and antique stores can also be a source. Both of my Freeston guides were found by doing searches among used and antique book listings on the Internet.

It would be hard to imagine traveling in Europe without a ubiquitous Michelin Guide, or going on a trip in the US without a Rand McNally Road Atlas. Adding a copy of one of Charles L Freeston’s books or an old Automobile Blue Book can make the trip more interesting, lots more fun, and somehow more adventurous than following the disembodied voice of a computer.

Copyright 2009 Kevin Clemens (speedreaders.info) edited and adapted from reviewer’s book Motor Oil for a Car Guys Soul, II

The High-Roads of The Alps: A Motoring Guide to One Hundred Mountain Passes

by Charles L Freeston

Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., Ltd. 1910

388 pages, 102 photographs, 11 maps

Automobile Green Book, Vol. 1: New England States and Trunk Lines West and South

by the Automobile Legal Association

Scarborough Motor Guide Company, 1922

896 pages

Original list price: $3.00

Automobile Blue Book: Vol. 1

Automobile Blue Books, Inc., 1925

772 pages

Original list price: $3.00

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Finding old guidebooks is surprisingly easy. Used bookstores usually have a small selection and antique stores can also be a source. Both of my Freeston guides were found by doing searches among used and antique book listings on the Internet.

Freeston’s style is one of British upper crust, mixed with genuine optimism for driving over alpine passes, surely one of the most difficult undertakings an early motorist could imagine.