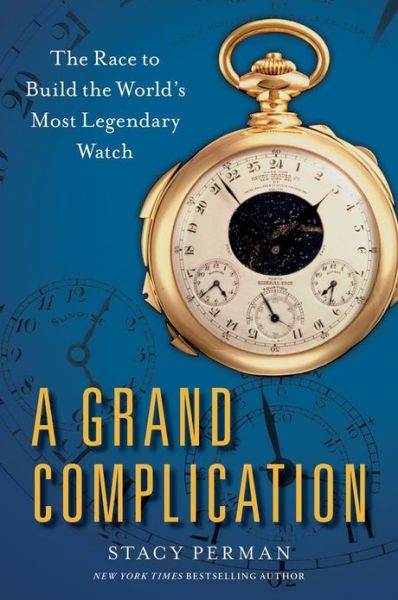

A Grand Complication

The Race to Build the World’s Most Legendary Watch

The Race to Build the World’s Most Legendary Watch

by Stacy Perman

One day in the mid-1960s, I went to an auction of fine watches at the Parke-Bernet Gallery on Madison Avenue. Parke Bernet was the biggest auction house in New York at the time. It subsequently became part of Sotheby’s which is still one of the first-tier auction houses for watches according to Forbes magazine.

I had been to the auction preview and became smitten with a small classic that typified understated Swiss style. After careful deliberation and a look at my bank balance I decided, as I stood before the shaving mirror the morning of the auction, that I’d be prepared to pay as much as $300 for that lovely object.

The opening bid, as I recall, was $2500 and went skyward from there. Such was my introduction to the tumultuous world of horology and the collecting of fine timepieces in America. (As a consolation prize I bought a Bulova Accutron Railroad watch, a minor classic that I still wear regularly.)

Stacy Perman writes about the love of watches and the drama of the auction room on a much grander scale. In 295 pages she successfully blends the biographies of two major collectors with a dollop of time-keeping history, in a book that reads at times like a spy novel.

Her story revolves around the competition between James Ward Packard (of Packard automobiles) and Henry Graves Jr. to own the world’s finest timepiece, though their definitions of “the world’s finest” varied slightly.

Packard might fairly be called an engineering intellectual. He was obsessed with mechanical contrivances to the extent he’d probably be called a “nerd” today. Trained at what is now Lehigh University (Bethlehem, PA), he founded an electrical goods company in his hometown, Warren Ohio, in the 1890a and amassed 40 patents while still in his twenties. A fastidious engineer and mechanical innovator, he cared more about building a superior machine than about cashing in on his genius. To Packard, the “finest timepiece” was the most mechanically elegant. For most of his life he continually challenged the European watchmakers he dealt with to make ever more exquisite time-keeping machines.

Henry Graves Jr., Packard’s horologic rival, was cut from different cloth. He was born into a sizeable fortune that he expanded in his years on Wall Street. He was a passionate collector of art objects, which to him included fine timepieces. His notion of “the world’s finest” was driven in part by esthetic preference and the eye of an educated collector. But his Wall Street banker roots demanded evidence that something deserved the claim of being “the world’s finest,” and so he particularly valued watches that had won certificates of accuracy issued by timekeeping observatories. He bought prize winners at every opportunity.

Perman sets the competitive struggle between these two collectors who both strove throughout their lives to commission new and more fabulous watches from Patek Phillipe, Vacheron & Constantin, and others against a background of watch making history. Beginning with the first portable time-keeping instruments, invented to my surprise back in the 16th century, she offers a comprehensive look at the technology as it has advanced over the last 500 years. “As watches developed,” she writes, “so did the watchmaker, from craftsman, to scientist, to entrepreneur.”

Early on, craftsmen began embellishing basic time-keeping instruments with “complications.” (Note: In the world of timekeeping, any function beyond simply telling the time of day is known as a complication. The Grande Complication of this story has 24 such! These include a perpetual calendar that will not need to be reset till 2100, split-second chronograph, exact time of sunrise and sunset in New York City, and phases of the moon. It will chime on the hour, half hour, and quarter hour, mimicking the chimes of Big Ben in London. It took three years just to design the movement, and five to build it. Graves paid Patek Phillipe $15,000 for The Grande Complication in 1925—the equivalent of $265,000 in 2013 dollars!)

Buyers, sellers, and the auction houses that bring them together are also a central element of the story. The description of the Sotheby’s auction of Henry Graves Jr.’s Grande Complication in the first chapter is nerve-wracking. One thinks for a moment of John Le Carré and MI5. In the end this pocketwatch that will fit in the palm of your hand and was commissioned from Patek Philippe by Graves in 1925 goes to a telephone bidder for $11,002,500! “The most complicated watch every created and the most expensive watch ever sold,” says Perman. (Patek did one with 33 complications, but not until many, many years later.)

The Grand Complication is a book for anyone who ever took apart a Westclox Big Ben at age seven. It teems with detail but the detail is vastly intriguing, and never boring. Wherever the author quotes a dollar figure from the past she is careful to translate it into current dollars which is not only helpful but also sometimes startling. The book contains many black & white illustrations and, in addition, a color centerfold with glorious illustrations of unusual and important watches. There are also extensive chapter notes, a full bibliography, and a comprehensive index.

Stacy Perman, a journalist, has worked for The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal and Business Week among others. She’s also written In-N-Out Burger, a behind the counter look at a fast-food chain. Much of her reporting in The Grand Complication is about J.W. Packard’s involvement in the early days of the car industry, and one might want to argue with Perman’s fact checker about some auto industry details, but most people will find very few nits to be picked.

Copyright 2019, Arthur Einstein (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter