Why Has America Stopped Inventing?

The author is a patent attorney with twenty years of experience in the field, filing patents for hundreds of inventors of all sorts, both corporate and private. He speaks frequently at colleges and technology forums and lives in Colorado.

His basic premise is that the complexity of the current patent process has reduced by half the number of patents issued per capita in the United States over the last 150 years. The end result of this situation is that the US has gone from being the world’s leading innovator to a laggard in the creative field, making the world a poorer place as a result. Instead of the average man coming up with startling new answers to current problems, inventing has become a corporate business that has all but priced out the little guy. Even when the common man does get a patent, wealthy corporate enterprises can easily work around it to avoid having to acknowledge the patent or pay royalties. The cost of patent litigation eliminates all but the wealthy taking up the defense of a patent, even if it is a solid and well-grounded one.

The majority of the book is an interesting and well-written quick history of the founding of the Patent Office, and the stories behind the major inventions of Eli Whitney (cotton gin), Goodyear (vulcanized rubber), Colt (revolvers), McCormick (grain harvesters), Morse (telegraph), Bell (telephone), the Wright Brothers (airplane), and Marconi (radio). Gibby’s point in retelling the stories behind those inventions is that the laws and rules governing the present day Patent Office would make these inventions non-starters in today’s world. In his legal opinion, patents for these key past developments would most likely be turned down, at least initially, on various technical grounds. Unless the individual civilian inventor has the money or corporate backing to re-file multiple times, they are unlikely to ever reap any benefits from their creative thinking. The author ponders about game-changing concepts and innovations we are missing today due to a patent process that makes it extremely difficult for a simple citizen to profit from his or her thinking. In his view, we lack solutions to current problems because the Patent Office has become too expensive and difficult to deal with, all but eliminating inventors who lack ready access to wealth. A good idea is no longer good enough.

In Chapter 20 (“Where Did The Inventors Go?”) Gibby asks, “Where are the likes of Goodyear, McCormick and the Wright Brothers today? The truth is that they are hard to find. The vast majority of today’s commercial products come from large companies¾ who aren’t set up to innovate. They are fantastic at marketing, complying with regulations, and keeping products safe, but they are not focused on inventing. As things stand, the successes of the nineteenth century are unlikely to be repeated.”

Although Bell Labs and IBM are mentioned, along with Steve Wozniak, Bill Gates, and Paul Allen, Gibby argues that “patents played almost no role in protecting the first computer operating systems.” In order to return to a world where patent law encourages inventing by the average citizen several things need to change. In the chapter “How Do We Fix This?” the author lists several things that he sees as necessary before change can occur. They include returning to the submission of a patent model that actually shows how the invention works (required until the 1880s), abolish the obviousness standard and the doctrine of equivalents (which pretty much initially kills most patent applications), cut the current twenty-year patent term in half, curtail the continuation practice (where the inventor or corporation holding the patent rights can re-file to broaden their claims at a later date), and go to a first-to-file system which would have prevented Alexander Bell from ripping off Elish Gray’s telephone patent application. “Bell managed to see Gray’s application right after it was filed and noticed Gray’s idea about transmitting voice signals electronically . . .” (Bell’s original patent was only for transmitting multiple telegraph signals over a single wire) “. . . . then copied the relevant paragraph and handwrote the same material in the margin of his own application, in essence stealing the idea from Gray.”

All in all, an interesting book to read simply for the history of the patent fights and double-dealing that lurks behind the popular myths about America’s famous inventors. As a disclaimer, I must admit that I make much of my living through patents that I’ve filed in the past, and that I agree with a great deal (but not all) of what Gibby has to say. I’ve had several patented products stolen by companies in the same field and have done nothing about it due to the huge expense involved. The cost to defend an issued patent, as my patent attorney business partner pointed out to me at the time, is frequently larger than any anticipated return to be gained through future royalties. It’s a rough world out there for inventors these days. Having a patent is more useful today from an advertising standpoint than thinking that the patent will help you defend yourself against copycat manufacturers. Far wiser to steal a good idea, make a few minor design “improvements,” and make the inventor spend his money suing you to stop making it. If he eventually wins, simply declare corporate bankruptcy and start over with a newly stolen product. It’s been done.

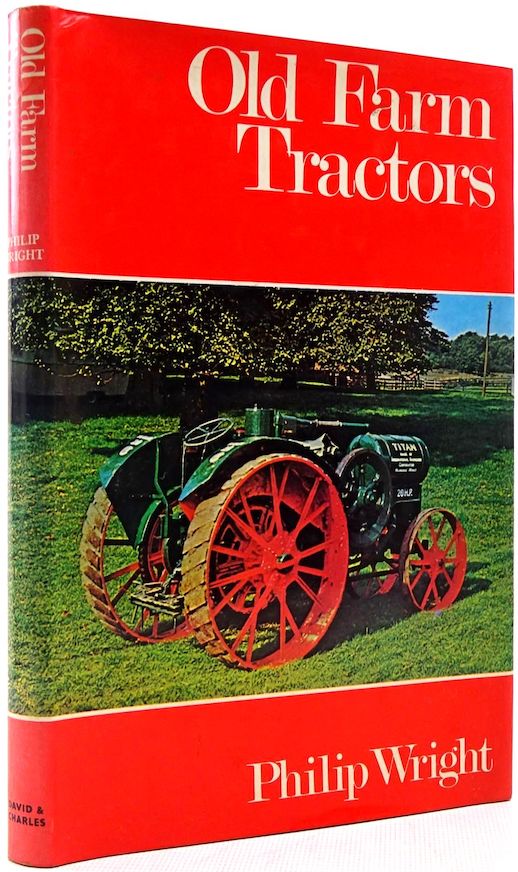

The book opens with a dedication to America’s Inventors, a Table of Contents, Preface, Introduction, then twenty-two Chapters, followed by About the Author, Resources, and References. There is no index, and the book suffers as a result. Typographical errors also creep in here and there, particularly when large numbers are being discussed. What, for instance, does 200,00 mean? Another shortfall is the total lack of photos of the people, places and inventions being discussed. For a link to a 15-minute interview with the author click here.

Copyright 2012, Bill Ingalls (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter