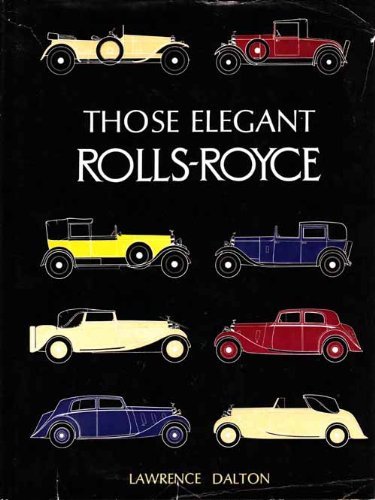

Those Elegant Rolls-Royce

by Lawrence Dalton

by Lawrence Dalton

This review touches upon several of the standard reference books that deserve a place in any decent Rolls-Royce library.

Nineteen Sixty-Four was a watershed year for the publication of serious, all-encompassing volumes on the history of Rolls-Royce motorcars in general and of the company’s early years in particular. That year saw the publication of The Rolls-Royce Motor Car by Anthony Bird and Ian Hallows and A History of Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, Volume One, 1903–1907 by C.W. Morton.

“Bird and Hallows,” as it is typically referred to by enthusiasts, has since enjoyed a remarkable publication history, being reprinted and revised through six editions, most recently in 2002. So highly regarded are the first five edition that it is frequently referred to as “the Rolls-Royce bible.” Unfortunately, the sixth edition was not as conscientiously edited as its predecessors as it introduced errors that have seriously undermined its status as the generally accepted argument-settling authority on the subject. The earlier editions remain the most readily available and accurate source of basic factual information on all models produced during those years covered by any edition. Virtually all serious enthusiasts know of it even if they don‘t have a copy in their library.

As to Morton, sadly, after a brilliant start, his invaluable volume turned out to be the only one of the intended trilogy, his untimely death preventing the development and publication of volumes two and three. Had those have seen the light of day, and had they included the same degree of exhaustive research and follow-up documentation, they might well have ultimately displaced Bird and Hallows as the unimpeachable authority. Both books are now out of print but are readily available at very reasonable prices at the various online book sellers.

Reviewers at the time of publication, while praising Bird and Hallows’ overall quality and thoroughness of technical information, decried the lack of variety in coachwork illustrations for the company’s various pre-WWII models. Since every pre-WWII Rolls-Royce was fitted with specifically commissioned coachwork to the owner’s requirements and was thus virtually unique, this was a legitimate criticism as it left a major portion of the story unillustrated. It didn’t take long for that shortcoming to be addressed, and by one of the marque’s recognized enthusiast coachwork experts, one Lawrence Dalton, Lawrie to his friends. Over the years he had amassed, or had access to, a vast collection of high-quality historic photos of coachwork on all the prewar models, as it was common practice for coachbuilders to record their finished products by commissioning professional photography of their craftsmanship just prior to delivery to the original owner. Dalton put together what is perhaps best described as a very high-quality photo album illustrating the incredible variety of styles and details to be found amongst the coachwork from the early years of the Silver Ghost (the original 40/50 model, as it was identified by the company) through the last year of peace prior to the outbreak of World War II in 1939.

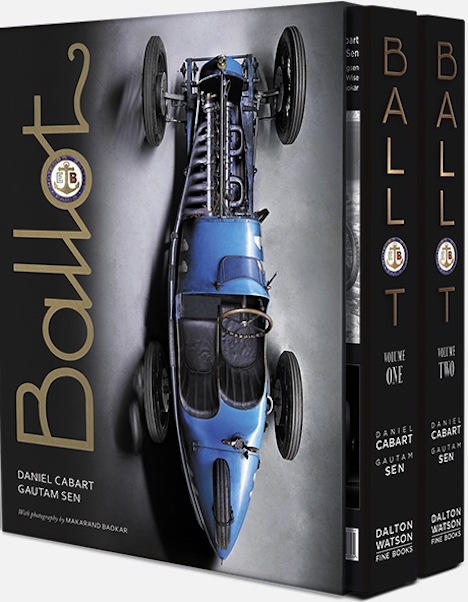

I think it fair to say that Dalton set his sights on Bird and Hallows as the standard to match for his own book. If the same quality materials, format, and physical dimensions were to be adopted, then due to its unusually heavy emphasis on high-quality historic photographs, optimally reproducing them would cause this to be a very expensive book to produce. It appears that none of the usual publishers of books of that quality were willing to take the financial risk on an unproven but certainly small market segment. Not to be deterred, Dalton formed his own publishing company, Dalton Watson Ltd., to carry out the project to his high standards, and in 1967 released Those Elegant Rolls-Royce, in exactly the same dimensions as Bird and Hallows, with nearly the same page count (well over 300). Coincidence? I think not.

Its publication was a gamble, as nothing of this scope had been previously attempted. It paid off, and rather handsomely. Demand proved sufficient for the book to be reprinted only a year later, then revised in 1970, reprinted again in 1972 and 1973, with a final revision in 1978. As stated above, its dimensions were identical to Bird and Hallows so it is highly likely that it was intended to be a complimentary companion volume to that book. The same costly, top-quality high-gloss paper is used throughout, and photographic reproduction is consistently top notch throughout as well. Of course, there are a few that are not quite as clear or sharply focused as the vast majority, but this is typically in the case of the more obscure coachbuilders of whom there are or were at the time of publication a half-century ago, very few known surviving high quality photos. Text, such as it is, other than captions, is limited to a single-page synopsis of the known history of the major coachbuilders whose volume of work and surviving photos were sufficient to warrant individual chapters. Of these there are fifteen (averaging a bit more than seven pages each) of the larger and better-known British firms, but not exclusively so. Brewster & Co. of New York receives its own chapter, and rightly so, but it is disappointingly short, in my not so humble opinion. Many of the smaller, lesser-known regional British firms have even shorter introductions and only a single photo to illustrate their craftsmanship and are often grouped two coachbuilders to a page. These smaller regional concerns, and all foreign coachbuilders with the exception of the aforementioned Brewster, totaling 45 in all, are crammed into the last 35-page chapter entitled “A Collocation Of Coachbuilders.” The revised editions saw the correction of the very few errors that slipped past the editors and in a few cases the substitution of better-quality photos, as well as the elimination of ownership credits in the first edition, no doubt due to their becoming outdated.

The vast majority of the photos in the book, typically laid out three to a page, are historic black and white portraits depicting the subjects as newly finished and ready for delivery. Total photo count is well over 500. Modern photos, of which there are a fair number, typically lack the formality of the historic photos taken professionally for the coachbuilder’s records and tend to stand out somewhat because of their more candid nature. There are four pages in color, depicting a total of five cars. The portraits themselves are almost exclusively profiles or front three-quarter views. Many of the historic professional photos include a uniformed chauffeur seated behind the wheel, which provides a meaningful sense of scale and shows just how massive some of the large-horsepower cars were, and conversely, just how diminutive some of the small-horsepower cars could be. We all know what the front end of Rolls-Royces look like, and since coachbuilders were required by the company to retain the radiator and shell, there are very few photos that prominently show the most famous radiator in the world. The book is, after all, a celebration of the diversity of coachwork, so there’s no need to waste space on unchanging hardware items. Not surprisingly, most of the cars shown have closed bodywork, especially from the mid-1920s on. After all, due to their year-round all-weather practicality saloons and limousines were the most commonly ordered bodies, but Dalton went to great lengths to include as much variety as possible. Sure, there are plenty of saloons and limousines, but even among them the variety, especially in the details, is remarkable and virtually all body types are illustrated with fine examples. It is highly unlikely that there are two identical cars in the book. This is where the very high quality of the original photos becomes apparent. Their consistent composition, quality of presentation, and lack of extraneous and distracting detail just screams “professionally done” to the knowledgeable viewer. The photographic technology of the times dictated that highly detailed, high-quality prints could only be produced from large-format negatives, the smallest of which that would produce acceptable prints was probably the commonly used 4″ x 5″ sheet film camera. More likely the larger 8″ x 10″ view cameras were used, which would have produced plate glass negatives. These were large, heavy, complex, and expensive items that were strictly professional in nature and in the field would require a two-man crew at a minimum, with three more likely.

A detail common to all the portraits and usually not noticed until it is pointed out (because it is difficult to notice what you can’t see) is the lack of passers-by, or any humans at all, with the exception of the aforementioned deliberately included uniformed chauffeur. That is no coincidence. Just one of the crew’s responsibilities was to control traffic around the subject so as not to spoil the composition. An unintended result of these professionally produced photos is that the consistency of presentation threatens to become boring. As overcast conditions are preferred for their greatly softened shadows that don’t obscure details and allow longer stopped-down exposures which produce sufficient depth of field of focus to capture them, there is an overall blandness or lack of contrast to them as well. That, along with the proliferation of dark-colored saloon and limousine bodies in the late Thirties, gives the viewer at first glance the misleading perception that this is primarily a redundant collection of closed body types. Just how interesting is that going to be? But the highly detailed photos encourage the viewer to take the time to carefully compare the bodies displayed on each page or two-page spread so as to observe their subtle differences. After all, every one of those details was carefully specified in the body’s build sheet. The devil, it is said, is in the details.

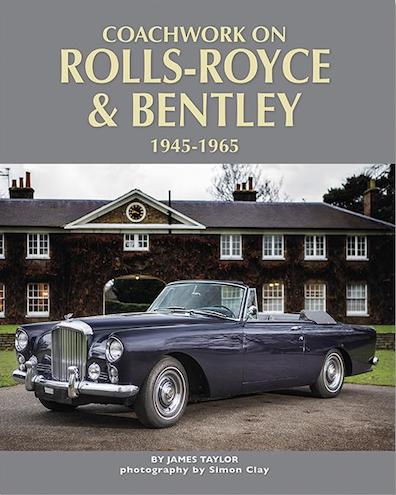

The formula, format, and overall quality of production represented such excellent value for the money that its commercial success became the cornerstone of an enduring publisher of fine books that continues to this day (albeit under new ownership). The success of this first book triggered a series of identically formatted dedicated histories heavily focused on coachwork for a wide variety of marques. There were ultimately several other volumes dedicated to Rolls-Royce and Bentley.

The sequel to Those Elegant Rolls-Royce, also limited in coverage to the pre-WWII era, Coachwork on Rolls-Royce 1906–1939, published in 1976, is so similar in all respects save dustjacket artwork, title, and page count that a separate review for it would only be redundant so we will devote a few words to it right here. It has an additional 150 pages, about 100 of which are data extracts from coachbuilders’ body books (a feature introduced in this second volume), and a photo count now exceeding 700. All the above comments apply equally to it as well. Except for the correction of one photo and caption, we observe no duplication of photos between the two volumes.

So, there you are. Between the two volumes one ought to be able to find a photo of virtually every type of body erected on the prewar Rolls-Royce. The 1,100 or so photos represent only a fraction of total production, but the reader, or perhaps viewer is a better term in this case, should keep in mind that as the Thirties progressed, the larger coachbuilders introduced designs that proved to be of enduring appeal, thereby justifying building them in batches of duplicates or near duplicates. While anticipating demand, especially in the high-end market can be very risky, it also allowed for substantial price reductions, a positive influence on sales that came to be of increasing importance as the decade progressed, the effects of the world-wide depression lingered and the demand for absolute individuality with its associated extravagant expense sharply declined.

Copyright 2022, Mark Dwyer (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

An excellent review !!!!