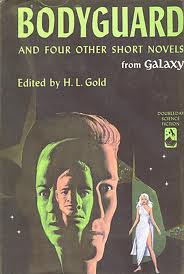

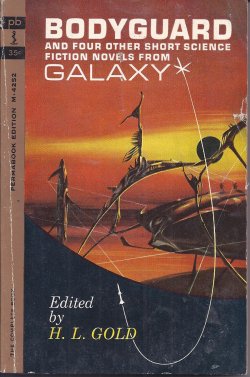

Bodyguard, and Four Other Short Science Fiction Novels from Galaxy

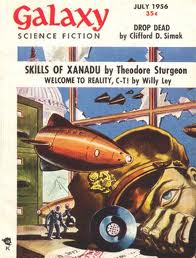

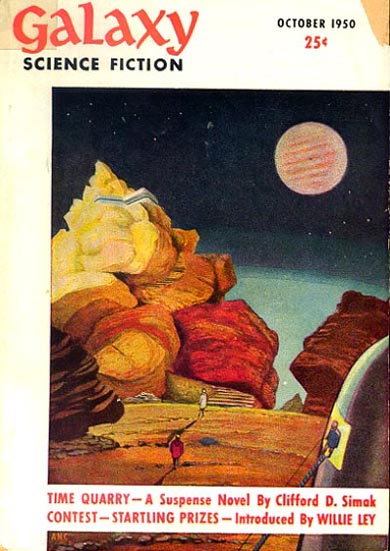

The Galaxy Science Fiction magazine was published from 1950 to 1980; it was revived briefly in the mid-1990s under the truncated title Galaxy. It was edited first by H.L. Gold then by Frederick Pohl, and was critically acclaimed from its start to 1969, when the magazine was sold and Pohl resigned. A list of some of the featured authors points to why the critical view remained so positive throughout the first nineteen years: Harlan Ellison, Robert Silverberg, Isaac Asimov, Theodore Sturgeon and Ray Bradbury. Gold envisioned a serious magazine, one that focused more on the social issues of the day rather than space cowboy adventures or standard fantasy fiction. That he was successful in this quest is shown by the fact that these original magazines are still in demand and are being bought and sold with regularity. Copies of Bodyguard, both hardback and paperback, are still being traded.

I purchased my copy in 1962, a new paperback, 35¢, missing the Doubleday hardback edition by two years. In 1962 I had yet to graduate high school, JFK was president, cars from Detroit ruled the world, the infamous Merriam-Webster 3rd edition was one year old, Sputnik’s orbital decay was but four years old, the Cold War had yet to thaw, and the Beatles’ first single, Love Me Do, hit the charts. And what is curious, the oldest novel in this anthology, Delay in Transit by F.L. Wallace, was already ten years old in 1962—and the other four stories were also from the 1950s: How-2 by Clifford D. Simak, 1954, Bodyguard by Christopher Grimm (actually H.L. Gold—but this fact is not mentioned in the book), 1956; and both The City of Force by Daniel F. Galouye and Whatever Counts by Frederick Pohl, 1959. This makes Bodyguard a kind of sci-fi bridge, a look backwards to a past future and a look ahead to the future past, all the while being suspended in the space of its own era, imagination, and conception.

I purchased my copy in 1962, a new paperback, 35¢, missing the Doubleday hardback edition by two years. In 1962 I had yet to graduate high school, JFK was president, cars from Detroit ruled the world, the infamous Merriam-Webster 3rd edition was one year old, Sputnik’s orbital decay was but four years old, the Cold War had yet to thaw, and the Beatles’ first single, Love Me Do, hit the charts. And what is curious, the oldest novel in this anthology, Delay in Transit by F.L. Wallace, was already ten years old in 1962—and the other four stories were also from the 1950s: How-2 by Clifford D. Simak, 1954, Bodyguard by Christopher Grimm (actually H.L. Gold—but this fact is not mentioned in the book), 1956; and both The City of Force by Daniel F. Galouye and Whatever Counts by Frederick Pohl, 1959. This makes Bodyguard a kind of sci-fi bridge, a look backwards to a past future and a look ahead to the future past, all the while being suspended in the space of its own era, imagination, and conception.

Despite moving house several times, the book is still on my shelf, and over the intervening decades, I have read it several dozen times. In essence, every few years a new person has read these stories, and, through the years, my reactions have remained quite similar. I always found The City of Force the weakest of the lot: Earth after a takeover by aliens, a country bumpkin journeying to the city to attempt communication with the gaseous beings, and the ensuing disaster of this attempt. This tale is too glib, too predictable, and it lacks the sophistication of the others. Perhaps it was meant as a Cold War fable, but to make that work, it would need to create an aura of paranoia and dread, but it fails to do so.

Bodyguard, on the other hand, with its interstellar chase, its presentation of zarquil, a procedure created by the Vinzz allowing humans (and humanoids, although interspecies action was frowned upon) to interchange their physical bodies, along with its smart plot twist, stands up well to repeated readings. Even the love interest is satisfactory. The plot twist essentially has a character stalking, with malicious intent, himself. I see this as a nod to the interest in the psychological concept of identity crisis that had surfaced during the 1950s. Delay in Transit also predicts interstellar travel, and the possibility of the personal computer. The computer is one that is physically inserted into the human body, a computer that can see in the dark, read minds, make predictions, and act as an all-around protector. Delay is of its time of writing, dealing with the problems of space travel, corporate espionage, and the prospect of a woman in charge of an important corporate entity—can she be trusted?

Bodyguard, on the other hand, with its interstellar chase, its presentation of zarquil, a procedure created by the Vinzz allowing humans (and humanoids, although interspecies action was frowned upon) to interchange their physical bodies, along with its smart plot twist, stands up well to repeated readings. Even the love interest is satisfactory. The plot twist essentially has a character stalking, with malicious intent, himself. I see this as a nod to the interest in the psychological concept of identity crisis that had surfaced during the 1950s. Delay in Transit also predicts interstellar travel, and the possibility of the personal computer. The computer is one that is physically inserted into the human body, a computer that can see in the dark, read minds, make predictions, and act as an all-around protector. Delay is of its time of writing, dealing with the problems of space travel, corporate espionage, and the prospect of a woman in charge of an important corporate entity—can she be trusted?

Although in most ways a well-crafted space-opera, Pohl’s Whatever Counts hinges on the efficacy of the science and practice of psychology, examining both the fears and the hopes that psychology engenders. But my favorite of the five has always been How-2. Office workers enjoy a five-hour day and a three-day work week, and they live most of their lives in the comfort of the suburbs. Leisure time is taken up by Doing It Yourself, brewing your own beer, adding rooms to your house, taking out your own tonsils, cleaning and fixing your own teeth, and building various robots—all the necessary kits being sold through the How-2 catalogs. The story revolves around one Gordon Knight (the name is not incidental to the theme) who instead of receiving a How-2 robot canine, winds up with an android who, using his skills in electronics, blacksmithing and engineering, reproduces. Imagine the chagrin of the How-2 company when it discovers that this prototype, that should have been mothballed because of the ruinous consequences inherent in its raison d’être, falls into the hands of our hero. Like Asimov’s earlier I Robot stories, How-2 contemplates the dissolution of the rigid line between the human and the machine, and the legalities and the conundrums of classification that would inevitably follow if robot-human equality became a concern of ethics and jurisprudence, making How-2, more than the other four, most apropos thematically to the concerns of our 21st century.

Although in most ways a well-crafted space-opera, Pohl’s Whatever Counts hinges on the efficacy of the science and practice of psychology, examining both the fears and the hopes that psychology engenders. But my favorite of the five has always been How-2. Office workers enjoy a five-hour day and a three-day work week, and they live most of their lives in the comfort of the suburbs. Leisure time is taken up by Doing It Yourself, brewing your own beer, adding rooms to your house, taking out your own tonsils, cleaning and fixing your own teeth, and building various robots—all the necessary kits being sold through the How-2 catalogs. The story revolves around one Gordon Knight (the name is not incidental to the theme) who instead of receiving a How-2 robot canine, winds up with an android who, using his skills in electronics, blacksmithing and engineering, reproduces. Imagine the chagrin of the How-2 company when it discovers that this prototype, that should have been mothballed because of the ruinous consequences inherent in its raison d’être, falls into the hands of our hero. Like Asimov’s earlier I Robot stories, How-2 contemplates the dissolution of the rigid line between the human and the machine, and the legalities and the conundrums of classification that would inevitably follow if robot-human equality became a concern of ethics and jurisprudence, making How-2, more than the other four, most apropos thematically to the concerns of our 21st century.

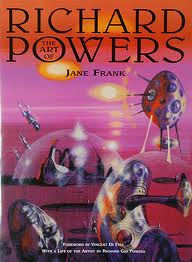

Overall, the prose of the anthology is at worst adequate and at best very good, especially keeping in mind that science fiction in the 1950s was really just coming of age in terms of sophistication and critical acclaim. Although not credited in my edition, the paperback cover illustration was done by Richard Powers (1921–1996), whose reputation remains strong to this day. Offering a generic but dramatic extraterrestrial scene, Dali-like in its conception, it is yet one more reason for me to have sustained interest in this particular science fiction volume throughout my last fifty years.

Overall, the prose of the anthology is at worst adequate and at best very good, especially keeping in mind that science fiction in the 1950s was really just coming of age in terms of sophistication and critical acclaim. Although not credited in my edition, the paperback cover illustration was done by Richard Powers (1921–1996), whose reputation remains strong to this day. Offering a generic but dramatic extraterrestrial scene, Dali-like in its conception, it is yet one more reason for me to have sustained interest in this particular science fiction volume throughout my last fifty years.

Copyright 2013, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter