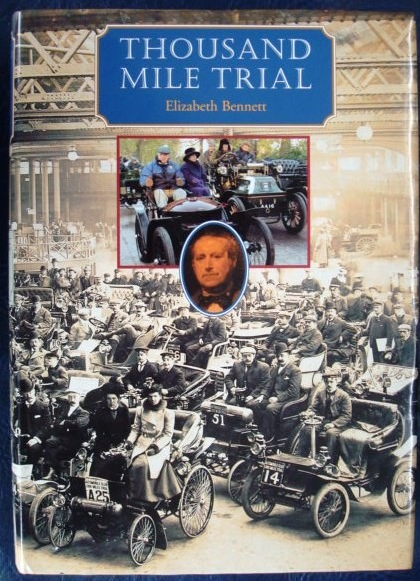

Thousand Mile Trial 1900

by Elizabeth Bennett

by Elizabeth Bennett

Published on the occasion of the centenary of the 1000 Mile Trial of 1900 this book does something no previous one—and there are piles—had done. It combines, for the first time, original news reports, participants’ own accounts, period and modern photos, postcards, flyers, ads, in short everything imaginable related to that event.

Some of the material has not been published before and even if it was, it was scattered in obscure places. In the more than twenty years this book has been in circulation, it has not been improved or repeated—it stands alone and it remains the benchmark.

This is a longish review so for the sake of the keen shopper, let’s cut to the chase: the book can still be easily found today on the second-hand market, and at prices that are still absurdly low compared to the premium production values and the author’s phenomenal research. I’ve had mine since the time it came out and it is by now well used and well loved. Even if your sole interest is hypercars or the cars of tomorrow, you cannot fully appreciate them without knowing how it all started.

The specific circumstance that brought this book about in 2000 rather than sooner was the May 2000 re-enactment of the event by the Veteran Car Club of Great Britain. Author Elizabeth Bennett had been that club’s Gazette editor since 1992 and their official photographer since 1996. Another unique circumstance that made it possible for the book to be as lavish as it is was the generosity of a benefactor, Tim Scott. Scott is a VCC member who felt he wanted “to give something back” to the hobby he so enjoys (at the time he ran two 1903 Mercedes). Thanks to his support it was possible to sell the book at the laughably low price of £35/$60. It was then a truly incredible value and it boggles the mind to think what its true cost would have been! Wish that every deserving project had such a patron.

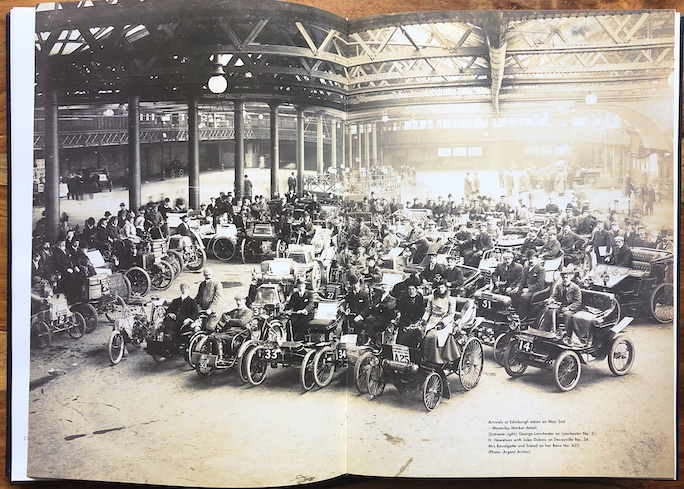

The book cover shows this same image but of course wrapped around the entire cover front to back. Here it is as one continuous image, showing the 52 cars that were still running on May 2, the Carlisle–Edinburgh leg.

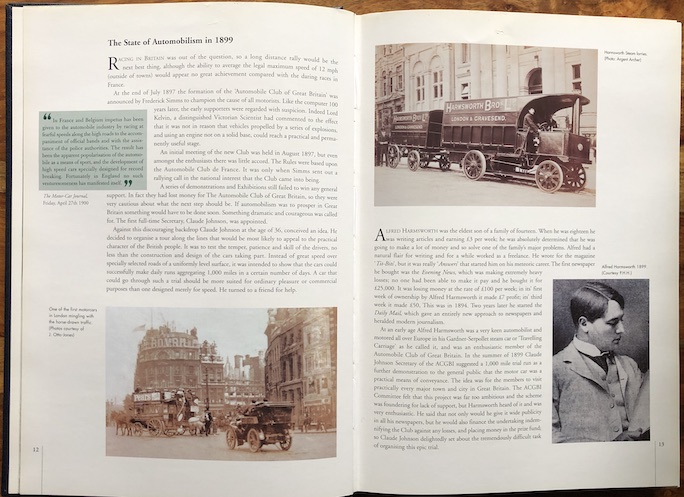

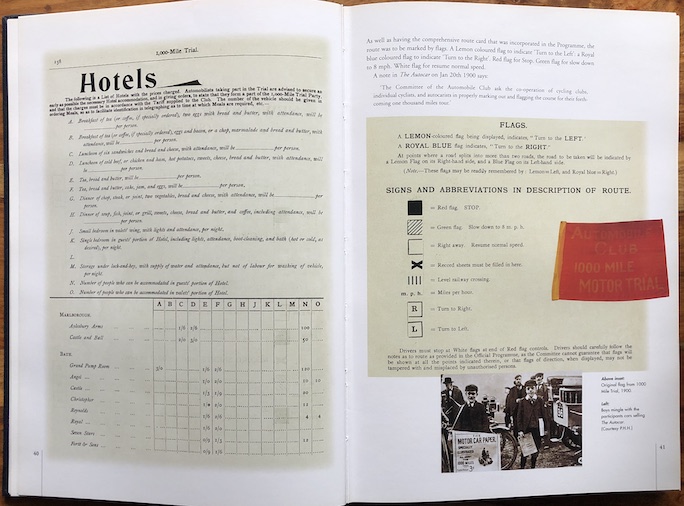

The book is satisfying on all accounts. Weighing in at 8 pounds it is not for the feeble-wristed! The heavy coated paper gives the book a majestic heft and is the perfect canvas for the beautiful period photos by Argent Archer. Generously laid out, the book has an opulent air. Design and typography (by the Wadsley Workshop) are of the “less is more” school of thought and are smartly conceived and beautifully executed. For instance, all quotes from The Autocar magazine are on yellow background and all quotes from The Motor-Car Journal on green background. The Index is exemplary and typifies just how much attention to detail went into this book. Not only does the index include photo references, it distinguishes between period and modern photos by the simple but effective device of employing different typestyles. Its depth and cross-references leave few questions unanswerable. It must be said: there are typos—but they are few and inconsequential.

Essential reading for understanding how the motorcar made its way in the world.

This book begs to be enjoyed unhurriedly. Lingering over the photos cannot fail to set in motion thoughts that will remind you that the motorcar is a part of a rich and wondrous tapestry of human endeavor. This old-car hobby of ours, at its best, can draw you beyond the mere collecting of cars. “The curious mind wants to know” is a good impulse to follow. Old cars, history, photography, sociology, mores, well-made books—if any or all of these subjects interest you this book will not disappoint.

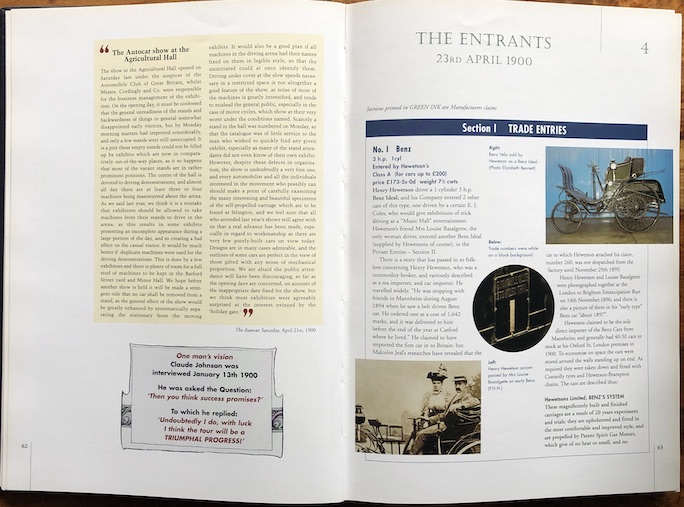

All sorts of period material bring the story to life.

To paint a picture:

The quotes from original sources must be taken with a grain of salt. That they are authentic is well established but, as the author herself points out, many of the reports contained conflicting and inaccurate data, not least because the subject matter was so novel. For the serious researcher and vintageant this does present obstacles and may require further investigation. But for what this book aims to accomplish, it does not detract from immersing oneself in the period.

The cause for these discrepancies is, largely, lack of knowledge on the part of the original writers. We have to remember that motoring then was in its infancy. In fact, the whole raison d’être for the 1000 Mile Trial was to “explain” and popularize this new fad. A common frame of reference had yet to be established, ergo drivers, for instance, stated different horsepower ratings for one and the same car. Journalists employed technical jargon they didn’t always understand. This was not just a new industry in its infancy, this was chaos without a vocabulary. Short of perpetual motion the cars in the Trial sported a bewildering variety of motive power: clockwork, carbonic-acid gas, electro-pneumatic, gunpowder, coal dust, compressed air, combinations of liquids, systems of levers or pendulums, gravity. Tiller steering, hot tube ignition—few but the inventors knew what they were talking about!

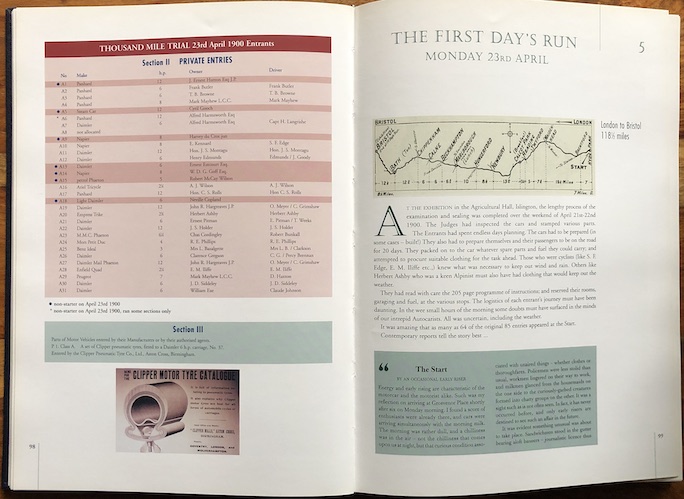

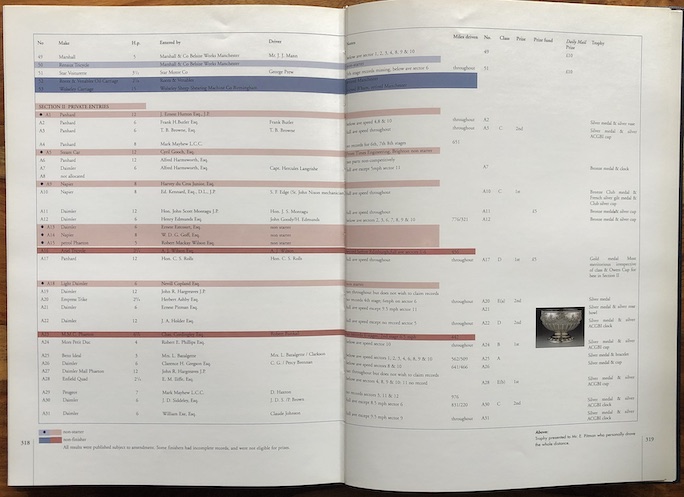

Each entrant, divided into TRADE and PRIVATE, is described by start number, make, vehicle specs, and owner/driver particulars.

To a modern reader, accustomed to a world of constant change, it will be difficult to imagine a time in which most people had not ever seen a car. Not only had they not seen a car, they didn’t like what they heard or read about it. Apprehension, skepticism, even fear were the order of the day. And not just for the “man in the street.” None other than the notable Victorian scientist Lord Kelvin opined that “vehicles propelled by a series of explosions, and using an engine not on a solid base, will not reach a practical and permanently useful stage.”

Each day is covered separately.

In addition to ignorance and disinterest, the hostile political environment presented a formidable obstacle. The 1000 Mile Trial accomplished for English motoring what the 732-mile Paris–Bordeaux race in June 1895 had done for France: it created awareness that the car was not merely a novelty, a plaything, but serious transportation capable of long-distance journeys over inhospitable terrain. And, not being restricted to iron rails or waterways, the car spelled serious competition to railroads and shipping lines. Not to mention the horse! This impact was not lost on the press or the public. The governing body of the French race became the Automobile Club de France. Its success in promoting motoring is reflected in the fact that within a year its membership rose to almost 2000.

A table of Results and Prizes.

Yet, English newspapers took little interest in these Continental stirrings. A year later, on October 15, 1896, Sir David Salomons organized the first public display of motorcars at his house at Tunbridge Wells. The few British pioneers—like Sir David, the Hon. Evelyn Ellis, Sir John McDonald—continued the good but lonely fight against crippling legislation and finally brought about the Locomotives on Highways Act of 14 Nov. 1896. Within days the newfound freedom was celebrated in the first “Emancipation Run” from London to Brighton. Alas, poor organization turned it into a PR fiasco, and it did nothing to impress the public.

Nonetheless, inventors continued to invent. By 1899 it was felt the infant industry was pulling into so many directions at once that the wheat needed to be separated from the chaff. Standards, consolidation, and direction were needed. Measuring British-made cars against product from the Continent would appeal to the patriotic spirit. Proving reliability would sway public opinion. And whatever was done to win general support had better work—or the press and public would simply turn a deaf ear.

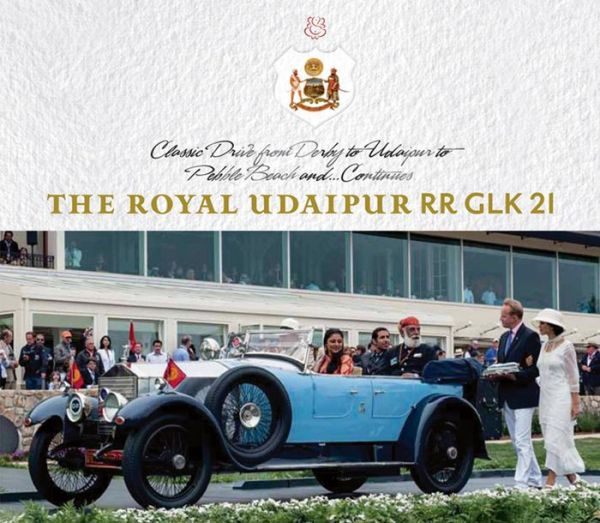

And so, one Claude Johnson, age 36, Secretary of the Automobile Club, conceived the grand idea of holding a 1000 Mile Trial. His vision of the future, his ability to organize, implement, delegate, cajole, inspire can simply not be overstated. In time, these skills would get him a job with Charles Rolls and then with Rolls-Royce where his massive and long-time contribution to the success of the company led to history referring to him as the “hyphen in Rolls-Royce,” with more than one writer expressing the notion that the cars really ought to be called Royce-Johnsons to reflect the enormity of his influence.

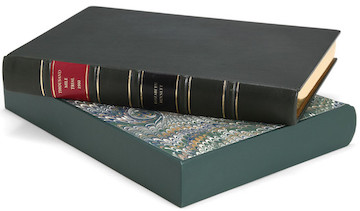

The main reason this book has remained such an undiscovered gem is that when new, it had practically no publicity because it had no mainstream publisher. Participants of the Centennial Re-enactment in May 2000 received a deluxe copy, a limited run of 120 that was autographed and bound in green leather with gilt-tooled spine, gilt-edged pages, and slipcase. Its original retail price was £200 and auction house Bonhams has sold several over the years, from as little as £125 to £500.

The main reason this book has remained such an undiscovered gem is that when new, it had practically no publicity because it had no mainstream publisher. Participants of the Centennial Re-enactment in May 2000 received a deluxe copy, a limited run of 120 that was autographed and bound in green leather with gilt-tooled spine, gilt-edged pages, and slipcase. Its original retail price was £200 and auction house Bonhams has sold several over the years, from as little as £125 to £500.

Copyright 2024, Sabu Advani (Speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

I really should stop following this website. Whenever a good review of a book I have not heard of is published, I have the compulsion to get a copy – despite my motoring library being full to capacity.

The book is everything that Sabu Advani has enthused. The magnificent pictures are worth the price alone (and I picked this up for a ridiculous £25). I’m primarily interested in 1950s / 60s / 70s motorsport but books like this on the origins of the sport are welcome, particularly when they are so all-encompassing and readable.

The David Baines book on Charles Rolls made the same way into my collection!