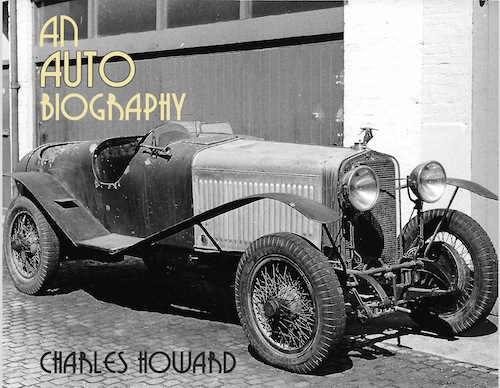

The Stewardship of Historically Important Automobiles

“Those restorers whose ethics supervene their economic aspirations will readily admit that some well-preserved cars surrendered their historical integrity to an anal propensity to achieve flawlessness.”

You are born, then you die.

If you drive a car you ruin it, simply by using it as intended (if you race a racecar you are more likely consuming it).

Left to themselves these processes are not reversible; no known physical process is.

Unless manipulated, atoms and molecules seek to decay. Unless manipulated, things that are assembled seek to return to a disassembled state. The only question is when. One practical question is: should you, must you, may you do anything about it? Should you manipulate? Even if you do you will, at least in this universe, only postpone not arrest the inevitable.

To wrestle with such questions, this compilation of essays enlists a veritable Who’s Who of individuals whose interests have brought them into situations that make them temporary custodians—as collectors, curators, restorers, dealers—of objects of “importance.” Just what it is that makes something important is difficult to pin down and, as well-intended—and necessary—as this book is, it cannot answer this question. Or very many others. But it does put a stake in the ground and it does attempt to define its terms, and in that regard it does represent a necessary step in these early days of the classic-car world learning to come to grips with the proverbial paradigm shift: to no longer look down upon unrestored cars.

On the face of it, the book title looks relatable enough to anyone with a “special interest” car. And it is—but in the same way a book about original Picassos may have something to say to those whose walls are adorned with Picassos torn from magazine pages. The parameters, advice, and concerns articulated in this book are first and foremost geared toward, for lack of a better word, elite automobiles that for whatever reason are deemed “important” and therefore entitled to “stewardship”—i.e. a behavior distinctly different from that required of the user of a merely interesting/rare/collectible/valuable car.

Another caveat: ponder the implications of the very first sentence in Fred Simeone’s Preface: “The desire to respect well-preserved great automobiles is not a new idea.” Does that mean a dilapidated barn find that has not been tended to in decades need not apply? And just what is a “great” car? It is ironic that the venue for the launch of this book was Bonhams’ October 2012 first-ever auction (at the Simeone Automotive Museum, the driving force behind this book) of unrestored vehicles that, while ringing up resoundingly strong sales, consisted of as many neglected as sensibly preserved ones including some in either camp that by no stretch of the definition could be called “great.” If there is a weakness in this book it is this sort of shorthand, these unspoken presuppositions that make such sense to their writers that they then do not perceive a need for further elaboration, leading to a lack of specificity sure to irk a whole lot more than the four groups Simeone addresses in his Introduction that is preemptively entitled “Whom Might we Unintentionally Offend?”

The book labors throughout to avoid the “You know it when you see it” syndrome in assigning importance to an object. That its tenets remain inconclusive is not for lack of trying to achieve objectivity but because, no matter how you slice it, there’s a lot of grey area: “Certain objects, whether through luck or character, transcend their normal utility and achieve historic importance.” Thus says Miles Collier to whom it fell to pen the first chapter. This may be no more than the luck of the draw but it’s a good thing it did because he deftly establishes a useful frame of reference by citing examples from the worlds of fine art and architecture to illustrate how such works were seen in their own time (namely: of no importance) and how the passage of time coupled with specific events or circumstances elevated some of them from “common” to “special.” Subsequent writers add insights from their specific areas of expertise. A recurring theme is that the car crowd is late in coming to the restoration vs. preservation discussion. Simeone attributes this to “the unusual way in which this hobby evolved” but nowhere is it made clear what those unusual ways are/were.

To the impatient reader or the one whose overriding interest is finding validation that their car is special, such expositions may look simplistic or contrived but they are neither, certainly not the former. Eleven of the twelve chapters are followed by Comments by Simeone and occasional Random Thoughts by him or others.

Since the merits of the book directly depend on its contributors’ place in the world we shall name names (that you will surely recognize; Ide is the Bonhams man who mounted the aforementioned auction but here writes as the former curator of the Larz Anderson Auto Museum): Fred Simeone (also the general editor), Miles Collier, Ed Gilbertson, Miles Morris, Leigh Keno, Leslie Keno, Mark Gessler, L. Scott George, Evan Ide, Malcolm Collum, Michael Furman (also the principal photographer, and publisher).

The outward appearance of the book (austere leatherette cover, no dust jacket) is surely no accident, evoking as it does an academic tome. On the inside, everything is as splendiferous in terms of paper, printing, typography, and generous use of space as any other book by this publisher. It is amply illustrated, even the non-car segments.

If the book leads to a lot of head-scratching it has served its purpose—consider it a Master Class, something for the advanced student who isn’t looking for superficial answers but criteria for making informed choices. Not least, concours folk may rethink the sort of over-restoration that spawns trailer queens one does not dare to drive. The “it’s original only once” dilemma needs much more exploration in regards to older restorations that, however well-intended and sympathetically done, have irreversibly broken the egg in order to make their omelette.

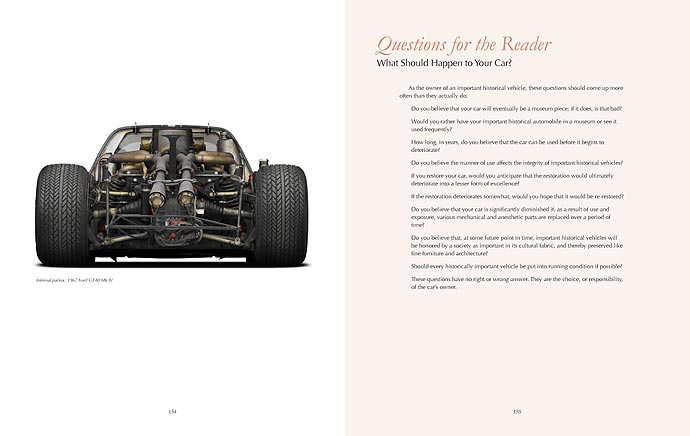

The book closes with a “Questions for the Reader” section—but that’s actually a really good place to start.

Copyright 2013, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter

Dear Mr. Advani,

I greatly enjoyed your review of our book. Your comments hit it right on! The idea was to get people to think about their historically significant car, how it should be managed and the responsibility as custodians to future generations who can learn from these objects as they do from fine furniture, paintings, and the like. Michael Furman tells me that sales increased abruptly after your review.

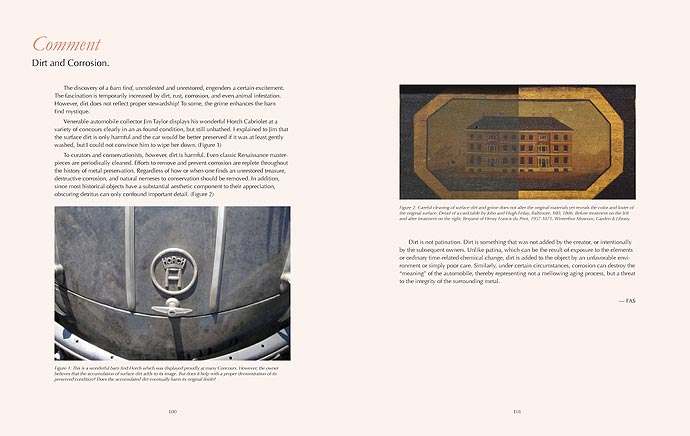

I want to explain why I am remiss in making certain points clearer, part of which attributes to the fact, as you mentioned, that those so close to a situation may omit an explanation of the point. I thought we did cover how the automotive “hobby” got off on the wrong foot, on page 14 in Miles Collier’s eloquent chapter. I tried to deal with the problem of the older restoration on page 104, but that page is only half full because I ran out of ideas, simply because there are no criteria. What to do with a nicely patinized car which is essentially not preserved because its original paint has been long ago removed remains a dilemma and therefore a fielder’s choice. I could go no further than that.

I did not imply that a barn find need not apply because it was not actively “preserved”. In this case, we discuss a preserved car wherein that word is intransitive. Some think that preservation is always an active process where we use “conserved”, the result of deliberate action. A car can be found in preserved state as we mentioned, simply because of benign neglect. So the barn find that has not lost its original materials and finishes despite how it was handled is still a preserved car.

I agree that our auction should not have been called ‘preserved’ cars, since some of them were wrecks. A better term is ‘unrestored’ cars, but Bonhams didn’t seem to like that. And frankly, some were actually restored and included simply because the consignor did not understand what we meant. As a first, low-budget auction, I believe it may ultimately become a site for people with truly preserved cars who hope that they will continue to be so in the hands of the next owner. There was no implication of ‘importance’ in that auction, however. You will note throughout the book, especially in Collier’s and my contributions, that there are soft criteria for importance.

We greatly appreciate the fact that you really got it! The superficial reader may believe that we are anti-driving, anti-restoration, and anti-alteration or that we are Museum guys who do not want to drive their cars. You know that none of this is true. At a symposium we recently delivered I closed with, “a driver wants his car to last to the end of the race; a collector until he sells it; a curator wants it to survive forever.”

—Fred Simeone