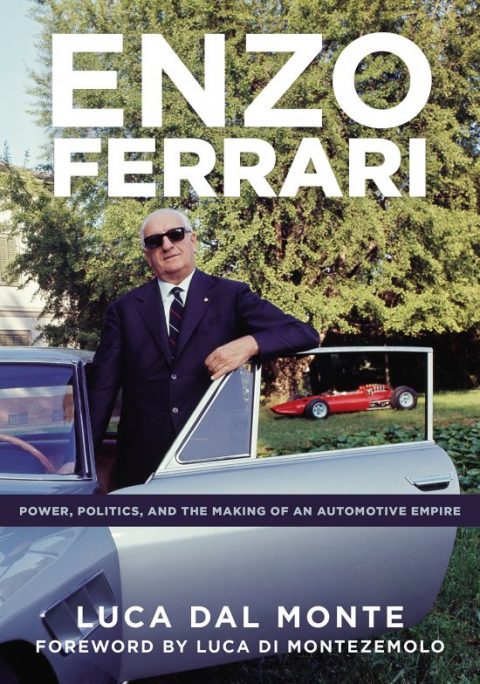

Enzo Ferrari – Power, Politics, and the Making of an Automotive Empire

“Ferrari was a genius of entrepreneurship, a visionary who possessed the ability to realize his dreams. After all, when asked how he wanted to be remembered, he famously replied: ‘As someone who dreamed of becoming Ferrari.’”

“Facts alone are wanted in life. Plant nothing else, and root out everything else.” Reread your Charles Dickens to find Mr. Thomas Gradgrind uttering these words in Hard Times. And facts, that’s what this almost 1000 pages long book puts on offer.

Seven and a half million. That’s how many hits I get by Googling “Enzo Ferrari book.” I am not surprised, as the Ferrari seam is a rich one that has been mined by a host of authors for decades. I have enjoyed reading more than a couple, most notably by British writer Richard Williams and the legendary American journalist Brock Yates. Whilst both informed me about things I hadn’t known before about il Commendatore, neither managed quite to capture the fullness of the man who, to recycle Winston Churchill’s words on Russia, was “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.”

Nobody in the automotive industry has left a legacy quite like Enzo Ferrari; just consider his eponymous marque’s successes over the last seventy years—the extraordinary sports cars, the huge tally of victories in Grands Prix, and the fact that the Prancing Horse is recognized throughout the world. And this is despite (because of?) the fact that a cynic might now regard Ferrari as a primarily an international merchandising brand, with a sideline in attention-seeking sports cars much loved by Premier League footballers and UAE sheikhs on the make. As for older Ferraris, what once were just obsolete racing cars are now blue chip investments, with the 250 GTO being comfortably the most expensive car in the world, selling at plutocrat-friendly prices of up to $48 million.

Nobody in the automotive industry has left a legacy quite like Enzo Ferrari; just consider his eponymous marque’s successes over the last seventy years—the extraordinary sports cars, the huge tally of victories in Grands Prix, and the fact that the Prancing Horse is recognized throughout the world. And this is despite (because of?) the fact that a cynic might now regard Ferrari as a primarily an international merchandising brand, with a sideline in attention-seeking sports cars much loved by Premier League footballers and UAE sheikhs on the make. As for older Ferraris, what once were just obsolete racing cars are now blue chip investments, with the 250 GTO being comfortably the most expensive car in the world, selling at plutocrat-friendly prices of up to $48 million.

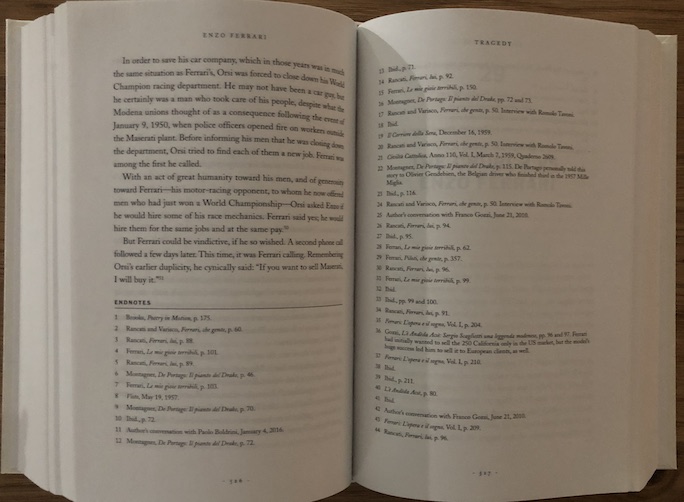

To write the definitive book on Enzo Ferrari is a hugely ambitious task, as it involves research into a mountain of material dating back to the day of Enzo’s birth. The fact that Dal Monte starts by devoting several hundred words to laying out why the date Enzo claimed (Feb. 18) doesn’t match the birth certificate (Feb. 20) sets the tone for the almost obsessive diligence he applies throughout the book. Each chapter’s source material is referenced to, typically, up to 70 endnotes (eg. “La Gazzetta dello Sport April 22, 1929”). The book runs to an exhausting 954 pages, divided into 49 chapters and, whilst modestly dimensioned at 10 x 6 inches and printed on relatively light-grade paper, it still weighs in at a hefty 3.5 pounds. It was first published in Italian in 2016, the English edition in 2018. The translation is almost faultless, with only the occasional clumsiness marring the text, such as the reference to the Monaco Grand Prix’s popularity with “. . . the racing community for its sumptuous participation prizes” and a reference to the Isle of Man as the “island of Mann.”

To write the definitive book on Enzo Ferrari is a hugely ambitious task, as it involves research into a mountain of material dating back to the day of Enzo’s birth. The fact that Dal Monte starts by devoting several hundred words to laying out why the date Enzo claimed (Feb. 18) doesn’t match the birth certificate (Feb. 20) sets the tone for the almost obsessive diligence he applies throughout the book. Each chapter’s source material is referenced to, typically, up to 70 endnotes (eg. “La Gazzetta dello Sport April 22, 1929”). The book runs to an exhausting 954 pages, divided into 49 chapters and, whilst modestly dimensioned at 10 x 6 inches and printed on relatively light-grade paper, it still weighs in at a hefty 3.5 pounds. It was first published in Italian in 2016, the English edition in 2018. The translation is almost faultless, with only the occasional clumsiness marring the text, such as the reference to the Monaco Grand Prix’s popularity with “. . . the racing community for its sumptuous participation prizes” and a reference to the Isle of Man as the “island of Mann.”

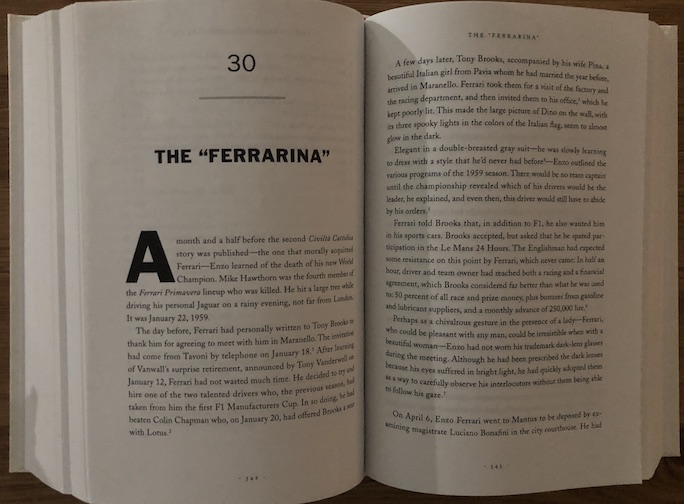

Dal Monte (b. 1963) tells his subject’s story in chronological order, and covers every facet of Ferrari’s life and work with a respect for detail that comes close to reverence for his subject. He did once work professionally for Ferrari/Maserati North America, handling corporate communications for four years so he does have an affinity for the brand (he had similar gigs with Toyota Italy and Pirelli, and also worked as a journalist and novelist). He writes with forensic clarity about Ferrari’s early days as the child who loved to race his brother Dino over a measured 100 m. Later he describes Ferrari’s own racing career as a driver, then the formation of the Scuderia race team in 1929 as well as the day in 1947 (“Wednesday March 12, around four in the afternoon,” in fact) when the very first Ferrari, the 125, was pushed out of the workshop in Maranello. Understandably, given Ferrari’s almost peripheral interest in his road cars, which were no more than an income stream to fund his racing, relatively little attention is devoted to the cars which merit the oft bestowed status of icon. These are machines like the achingly lovely 275GTB, the car whose lines can still reduce the author of this review almost to tears. But it is Ferrari the man whose life and legacy truly fascinates because, as Luca di Montezemolo (Enzo’s erstwhile assistant, then race team manager, and later Ferrari president) says in his Foreword, Enzo Ferrari was an “intentional prisoner of his own myth.”

Dal Monte (b. 1963) tells his subject’s story in chronological order, and covers every facet of Ferrari’s life and work with a respect for detail that comes close to reverence for his subject. He did once work professionally for Ferrari/Maserati North America, handling corporate communications for four years so he does have an affinity for the brand (he had similar gigs with Toyota Italy and Pirelli, and also worked as a journalist and novelist). He writes with forensic clarity about Ferrari’s early days as the child who loved to race his brother Dino over a measured 100 m. Later he describes Ferrari’s own racing career as a driver, then the formation of the Scuderia race team in 1929 as well as the day in 1947 (“Wednesday March 12, around four in the afternoon,” in fact) when the very first Ferrari, the 125, was pushed out of the workshop in Maranello. Understandably, given Ferrari’s almost peripheral interest in his road cars, which were no more than an income stream to fund his racing, relatively little attention is devoted to the cars which merit the oft bestowed status of icon. These are machines like the achingly lovely 275GTB, the car whose lines can still reduce the author of this review almost to tears. But it is Ferrari the man whose life and legacy truly fascinates because, as Luca di Montezemolo (Enzo’s erstwhile assistant, then race team manager, and later Ferrari president) says in his Foreword, Enzo Ferrari was an “intentional prisoner of his own myth.”

Dal Monte writes in a dispassionate, almost anonymous, style about Ferrari’s near century-long saga of intrigue—he was a master of rumor and nuance. He describes Ferrari’s losses, none more moving than the death of his only son, Dino. Then there is the Machiavellian plotting—against Alfa Romeo, his own drivers (and also technicians) and the motor racing establishment. And also his infidelity—his long marriage to Laura was not happy. But most of all, Ferrari’s legacy is one of triumph as, by the end of 2018, his team had won 235 Grands Prix, more than any other.

Although Dal Monte does not skirt around the technical aspects of Scuderia Ferrari’s machinery, it is the accounts of Ferrari’s tempestuous relationships with his race drivers that enliven the book. Without such insights into human drama, the book would have risked sinking beneath the waves, so overloaded with its cargo of facts does it sometimes feel. But both the number and nature of the feuds and tragedies that punctuated Ferrari’s long life serve to leaven Dal Monte’s diet of incidental and often inconsequential facts. It can still be a tough book to digest, though. For example, an en passant reference to the contents of L’Ilustrazione della Guerra e La Stampa Sportiva (“number 26, published on Sunday June 27, 1915”) reads: “About mid-page, the smallest of three photographs featured Ralph DePalma, a driver virtually unknown to the Italian public.” Indeed.

Although Dal Monte does not skirt around the technical aspects of Scuderia Ferrari’s machinery, it is the accounts of Ferrari’s tempestuous relationships with his race drivers that enliven the book. Without such insights into human drama, the book would have risked sinking beneath the waves, so overloaded with its cargo of facts does it sometimes feel. But both the number and nature of the feuds and tragedies that punctuated Ferrari’s long life serve to leaven Dal Monte’s diet of incidental and often inconsequential facts. It can still be a tough book to digest, though. For example, an en passant reference to the contents of L’Ilustrazione della Guerra e La Stampa Sportiva (“number 26, published on Sunday June 27, 1915”) reads: “About mid-page, the smallest of three photographs featured Ralph DePalma, a driver virtually unknown to the Italian public.” Indeed.

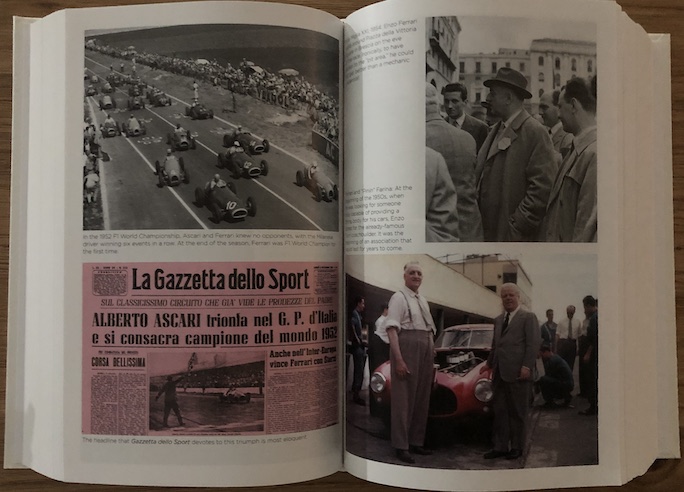

Enzo’s own autobiography had been entitled Le mie gioie terribili (My Terrible Joys, H. Hamilton, 1963). If that book had been about almost anyone else the title would have been melodramatic, possibly even bathetic, but for Ferrari’s own story, in his own words? Not a bit of it, because, as Dal Monte recounts, for almost every success Enzo Ferrari’s team enjoyed, the price paid was brutal. Such as the decay of a once valued relationship into toxic hostility, as occurred in the mid 1970s when young pretender Niki Lauda supplanted Clay Reggazoni’s status as Maranello’s favored son. Or the vengeful way in which another of Ferrari’s greatest drivers, John Surtees, was fired in 1966. Not, as the popular myth has it, as a result of the fallout at Le Mans with team manager Dragoni, but by Dragoni acting under “a reserved and personal communication from Enzo Ferrari, one of those that could not be disregarded.” Most of all, there is the near endless succession of deaths of Ferrari’s racing drivers that, following the death of Luigi Musso in 1958, resulted in the Catholic church itself condemning Ferrari (but curiously, not specifically by name) as “A modern Saturn become industrial tycoon, he continues to devour his sons.” Ferrari’s own vale of tears was populated by men such as Guy Moll and Alberto Ascari, Wolfgang von Trips, Ignazio Giunti and, in more recent memory, Gilles Villeneuve but Dal Monte reminds us that there were so many more.

Tazio Nuvolari died in relatively old age, in his own bed, and yet, to so many, he still is the epitome of the Italian racing driver. He was both friend and sometime enemy of Ferrari and I enjoyed reading Dal Monte’s account of how, on Nuvolari’s return to the Alfa Romeo team in 1935, Ferrari (paraphrasing Dante) wrote “Your black shadow, once departed, comes back.” But one name, Dino, is the most evocative of all. Ferrari’s only son, mourned by his father, both publically and privately, from his death at 24 to Enzo’s own 32 years later at 90. Dal Monte’s account of “the greatest sorrow” of Enzo’s life is respectful and comprehensive, describing the almost daily visits to Dino’s grave and the legacy in the form of the car that bore his name, powered by the V6 engine Dino had championed.

Dal Monte’s book resembles a thesis more than a conventional biography and, although I have read about every facet of Ferrari the man, I still know little about the author’s own opinion on his subject. I sense that, for Dal Monte to have allowed his own personality to intrude by expressing personal opinion would not only have been unnecessary but would have felt disrespectful to his subject. This work is not a lively read, therefore, and I will confess to having sometimes looked for an excuse to put the book down to find respite in more colorful prose. But the greatest praise I can give is to say that the book deserves to become the definitive one on its subject.

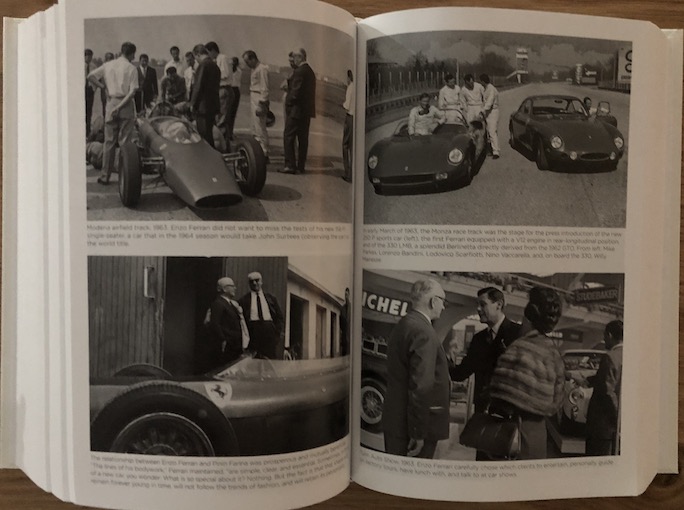

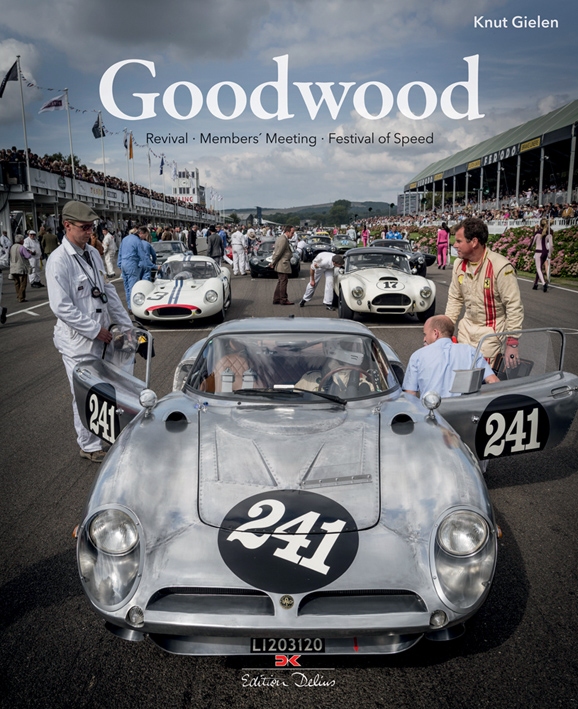

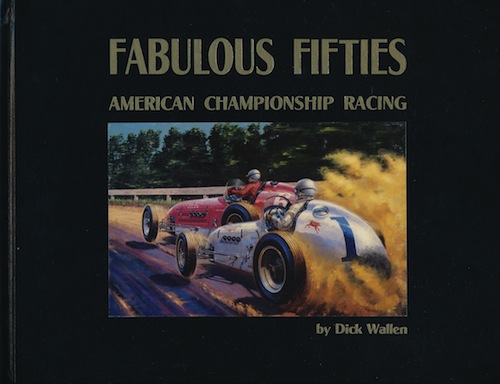

The Index is quite exemplary; the photos are bundled into 6 sections ergo are not specifically placed with their corresponding text but of course do follow the narrative.

I will end this review with a question, and it’s one I don’t ask rhetorically: Why is there not an opera about Enzo Ferrari? Modern opera includes a catholic selection of subjects, from Jerry Springer and Leon Klinghoffer to Richard Nixon and Robert Oppenheimer. Yet I struggle to think of anybody more suited to dramatization in libretto than the triumph and tragedy that was Enzo Ferrari. All the source material needed, and much more besides, is to be found in Luca Dal Monte’s meticulously researched book.

Copyright John Aston (speedreaders.info)

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter