Mercedes-Benz Supercars: From 1901 to Today

“No man is an island,” so the saying goes. But not in this book. It would have you believe that nothing of note exists outside the Mercedes world. Every model, every person, every part down to the lowliest O ring is the absolute supreme best. Even a dyed in the wool M-B enthusiast should have the decency to be embarrassed by such overzealous drum-beating.

One thing the book does do nicely is making the arc from then to now, certainly in the philosophical realm of wanting to produce whatever the most super of the supercar idiom of the time was and is. Although over the years M-B has offered models for every wallet size and every purpose, the firm has never not had a high-performance road car in the line-up (or at least in the works) and for that it deserves recognition. But wanting and actually achieving are very different things and in the latter regard, the book is totally mum. Therefore, as a cheerleading exercise for M-B, the book is a winner, as a balanced view of M-B’s place in automotive history, not so much.

This is the English version of a book published in German two years earlier, Mercedes-Benz Supersportwagen: von 1901 bis heute (Heel, 2010, ISBN-13: 978-3868522990). If you have an ear for such things you will hear the German syntax in the English translation which often enough seems to make no effort at all to make itself intelligible. Random example? Page 173: “Revolutions sometimes begin small. This one is stormy already: ‘No bellowing motor, no pulsating drive train. Out of nothing comes surreal propulsion in over the passengers,’ Marcus Peter admires in auto motor und sport: ‘One is more shot down than hastened.’” Surreal indeed. Sure, you’ll eventually figure out that the last sentence probably means “accelerating, as if shot from a cannon” but do the words have to be so clunky?

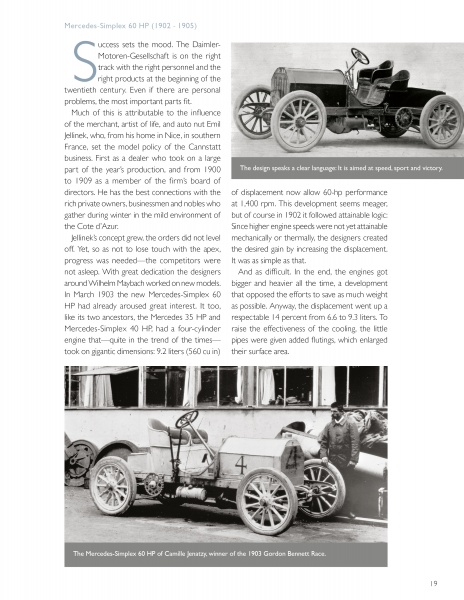

Eighteen cars are discussed, from the 35 hp of 1901 to the SLS AMG. In relative terms, the early cars really did go improbably fast and one shudders to think how physically hard these machines were to handle. Thinking of that is left to the reader’s imagination although there’s a nice description of the complex procedures of just starting a 1902 Simplex, the oldest surviving M-B. Also left to the reader’s initiative is realizing that there must be more skins to the onion. While the book, for instance, effusively hails chief designer and later technical director Wilhelm Maybach as “king of constructors” there’s not a word about what else he and his family did: Zeppelins. Or, for that matter, the role of the Maybach name in the modern-era Mercedes portfolio. Books that are too one-track single-minded may well be nice, but they’ll never be great, must-have cornerstones of a decent automotive library.

Eighteen cars are discussed, from the 35 hp of 1901 to the SLS AMG. In relative terms, the early cars really did go improbably fast and one shudders to think how physically hard these machines were to handle. Thinking of that is left to the reader’s imagination although there’s a nice description of the complex procedures of just starting a 1902 Simplex, the oldest surviving M-B. Also left to the reader’s initiative is realizing that there must be more skins to the onion. While the book, for instance, effusively hails chief designer and later technical director Wilhelm Maybach as “king of constructors” there’s not a word about what else he and his family did: Zeppelins. Or, for that matter, the role of the Maybach name in the modern-era Mercedes portfolio. Books that are too one-track single-minded may well be nice, but they’ll never be great, must-have cornerstones of a decent automotive library.

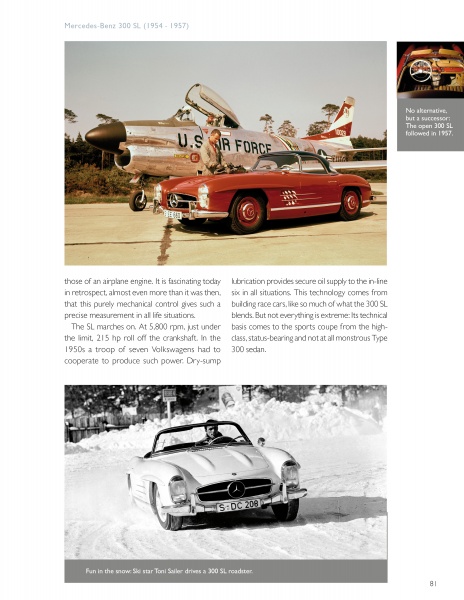

Coverage of the models is fairly even in terms of length but, not surprisingly, the 300 SL/SLR take pride of place. If there is a gap in M-B’s supercar ambitions it is the period between those models and the C 111 (1969) and 112 that are too often relegated to footnotes elsewhere. This section is particularly noteworthy for the inclusion of styling exercises, cutaways etc. Technical data is provided for all models in the form of tables in the respective chapters. Illustrations are plentiful, well reproduced, and placed well within the text. As they are mostly M-B stock photos, old hands will have seen many of them before.

When all is said and done, the book does get across its key message: M-B has been at the supercar game a long time, has an almost unbroken history of improving the breed by trickle-down technology from racing/high-performance programs, and the enjoyment of your supercar can only benefit from getting to know its ancestors. As long as it’s an M-B.

Copyright 2013, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter