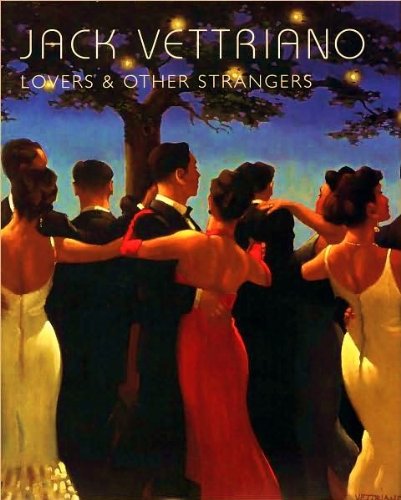

Lovers and Other Strangers: Jack Vettriano

“These things, the motives of such people, were obscure—a little alarmingly so; they contributed to that element of the impenetrable….”

—Henry James, The Golden Bowl

Somehow there is a strange sort of inverse relationship between Jack Vettriano (born Jack Hoggan, 1951) and Norman Rockwell (1894–1978). Rockwell’s paintings, which had graced many of the classic Saturday Evening Post magazine covers, for a long time had been considered merely illustration and kitsch, but in the last four decades or so have been reevaluated and considered by some to be viewed as fine art. Vettriano had always considered himself working as a fine artist, but more than a few critics found his work to be merely illustrative, more, well, Rockwellian—in, granted, a noir, erotic manner. Weird that. The critics that too easily dismiss Vettriano are just plain mistaken.

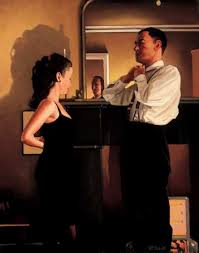

This artist, self-taught, holds a fascination with dusky liaisons, women in gartered black stockings, men in fedoras and braces—a style that reflects old crime movies and dime novels, cheap hotels and elegant brothels, midnight encounters and icy passion, but a style that only approximates all of these, a style obscure and indefinite, a style from an imagined past that falls somehow between the 1940s and some distant tomorrow.

Most of his paintings reflect this style but not all. Consider, for one, The Singing Butler: a well-heeled young couple waltz in the rain at the seashore with the butler and the maid in attendance. Because of its popularity gained through thousands of reproductions sold and the subject matter leaning towards affectation and sentimentality, this piece, more than others, helped drive and vindicate those critics ready to ignore or downplay Vettriano. The fact that most if not all of his showings were sold out and that The Singing Butler, the original, sold for $1.3 million at Scotland Sotheby’s can surely be considered a vindication of its own.

Most of his paintings reflect this style but not all. Consider, for one, The Singing Butler: a well-heeled young couple waltz in the rain at the seashore with the butler and the maid in attendance. Because of its popularity gained through thousands of reproductions sold and the subject matter leaning towards affectation and sentimentality, this piece, more than others, helped drive and vindicate those critics ready to ignore or downplay Vettriano. The fact that most if not all of his showings were sold out and that The Singing Butler, the original, sold for $1.3 million at Scotland Sotheby’s can surely be considered a vindication of its own.

Vettriano knows quite well how to render light, whether blindingly stark at the seashore, cut flat on a winter’s evening or emitted from a dim lamp in a darkened passage. And there is, too, in his work, a misplaced hint of Balthus, a touch of Alex Colville and, perhaps, even, a bow to René Magritte. Some have considered too many of the paintings to be pornographic. Vettriano replies: “Anyone who says it’s pornography just hasn’t seen pornography.”

Vettriano knows quite well how to render light, whether blindingly stark at the seashore, cut flat on a winter’s evening or emitted from a dim lamp in a darkened passage. And there is, too, in his work, a misplaced hint of Balthus, a touch of Alex Colville and, perhaps, even, a bow to René Magritte. Some have considered too many of the paintings to be pornographic. Vettriano replies: “Anyone who says it’s pornography just hasn’t seen pornography.”

The book itself is compact but beautifully designed. The endpapers are golden. On some of the pages that display a given painting (sometimes two adjoining pages are used) a small rectangle is also found in the white border showing a detail from that painting. These details are often unlike what one would expect; they magnify a telling feature that might otherwise be ignored. The text, a history of the man, his paintings and his critics, is printed in clear, pleasing font and is tastefully illustrated. This small book offers as much, perhaps more, satisfaction than a larger, heavier book would. Not for everyone, but if the above descriptions at all entice, find a copy and spend a late evening or a wee hour in Jack Vettriano’s world.

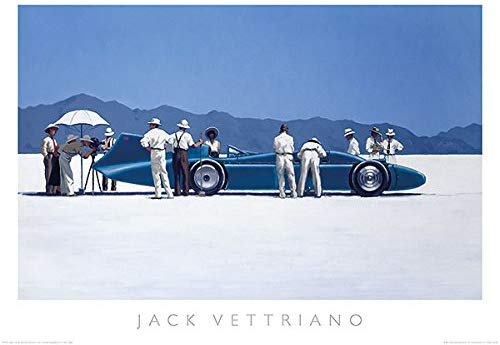

PS: Since, after all, this is speedreaders.info, car enthusiasts will like the artist’s painting Bluebird at Bonneville, a picture of Malcolm Campbell’s land speed record car, produced by Vettriano’s own publishing company to mark the 75th anniversary of Campbell’s final LSR. Londoners may recall that this was one of a set of seven paintings Sir Terrence Conran had commissioned in 1996 for his new Bluebird Gastrodome in the building of the original Bluebird Motor Company in 1923. The set sold for over £1m in 2007.

Note: There are variations of this book in size, content, and cover art.

Copyright 2019, Bill Wolf (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter