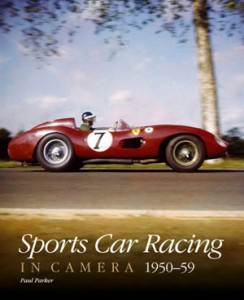

Sports Car Racing in Camera 1950–59

by Paul Parker

by Paul Parker

“These places were unforgiving of error, as were the cars; and the hooligan driving tactics that so define modern racing were not acceptable or possible (with certain notable exceptions) unless, of course, you wanted to die.”

This is the third In Camera book about sports cars by this author and this publisher (there are also three F1 books, with more of each coming). As the title would suggest, it is the photographs that are at the core of this series. Readers who already know any of the other books will have high expectations, which will not be disappointed here, but they would do well do first reflect upon the historical context for this decade—or consult the first couple of paragraphs in the Introduction. The very factors that give this decade, compared to later ones, a degree of singular variety are the same that make it difficult to treat each year, each season, with the same level of magnification or uniformity.

Blame history, not the author! For all those countries that had been affected by the havoc wrought by World War Two these were formative years in every area of civilian life.

In terms of the renaissance of motor racing the first few years in that decade especially had some rough spots, be it the record-keeping, the condition of race venues, or the depth of the field in regards to drivers and machinery. Swiss-based freelance writer Parker’s treatment of these years is therefore informed by his own sense of how to best add to the already existing photographic record, the greater good being to show what is new rather than what is expected (which is only expected because it is already known). The only reason to even point this out is to prevent some trigger-happy reader from sending hate mail to the publisher complaining that any book worth its salt should have contained this or that.

Books are unlike most other consumer products. The more intelligent a book the less it seeks to rehash what is already written elsewhere. This is but one reason why SpeedReaders reviews eschew qualitative comparisons. That said, there is no favoritism or prejudice in saying that Parker’s books are the proverbial “cut above.” The writing is competent, fluid, with a full grasp of the macro and micro detail (which is not to say there may not be the rare hair to split), and the photo research is simply outstanding. If you already own every book on the subject, and there is quite a number, you will still see so many new things here that not having this or the other two books in the series would be a loss.

Readers new to the subject will not just want to first read the Introduction but also the last chapter, “Final Thoughts,” so as to fully appreciate the forces at work during these important years. A new generation of drivers joined the thinned ranks of prewar pilots, tired prewar machinery was up against new cars using new materials and new techniques, the emerging purpose-built race tracks challenged drivers who had acquired their skills on road courses, and wealthy privateers still held their own against works drivers. Parker deftly weaves all these strands together. Divided into years, each year’s coverage begins with a two-page commentary that sets the scene by talking about drivers, cars, manufacturers, regulations, and anything else that has a bearing on the racing season. The remaining text is all in the form of detailed photo captions. Aside from describing the obvious—who, what, when, where, why—Parker does the reader an immeasurable service by drawing the eye to such minutia as the time on someone’s wristwatch, the initials on a toolbox, a piece of equipment barely visible in the periphery, the deeper meaning behind a windshield wiper being positioned just so. You learn to “read” a photo and school the eye to develop a forensic approach. Most of this sort of detail could simply not be conveyed in linear, contextual narrative because it would fall outside the scope of the text that is required to carry the story forward. That Parker is able to point these things out means, obviously, that he himself saw them first—and that is the quality that sets his books apart.

As the decade unfolds, the coverage grows from first 15-odd pages per year to 20–30. Black & white photos increasingly give way to color but the first color one shows up as early as 1952 (none are credited, by the way), a rarity for the time. If you know photo film you will of course note the distinctive colorcast that stems from the emulsions in use then. Each year ends with a multi-page summary of teams, drivers, and results. Most of the photos are large; all are exceedingly well reproduced. An oddly thin Bibliography lists books the author consulted (which is of little use to the newbie who would want a list for further reading); the Index leaves nothing to be desired.

No, this is not the only book you’ll want about this era, but you will find it adds singular texture.

Copyright 2017, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter