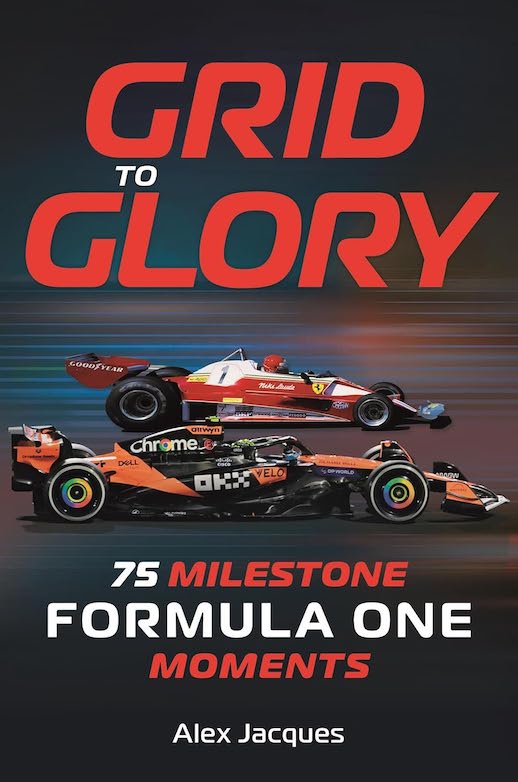

Grid to Glory: 75 Milestone Formula One Moments

by Alex Jacques

“If those two have kids tonight I might as well retire now.”

—Patrick Tambay, expressing the possible consequences of Gilles Villeneuve and Alain Prost having shared a mattress at Kyalami during the 1982 driver strike.

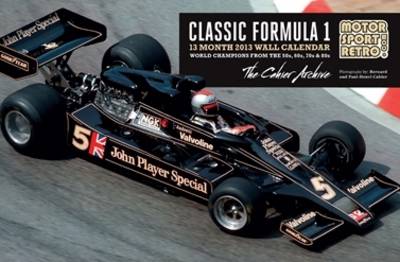

Have you heard? Formula One turned 75 this year and Grid to Glory is just one of a whole raft of books commemorating the anniversary.

Yes, I know, it’s compulsory for old geezers like me to point out that it’s not the 75th at all, that the 1952/53 seasons were contested by Formula Two cars but, y’know, the sky won’t fall if we let this go. I’ll leave the pedantry there because I don’t want to sound like one of those Nineties’ weirdy beardies saying we should party like it was . . . uh . . . 2000.

The book, then? The author is well known to UK terrestrial TV audiences as the lead commentator on Channel 4’s Formula One coverage, and he’s also the voice of F1 digital output. He might lack predecessor Murray Walker’s trademark “trousers on fire, even in moments of tranquillity” style, but he also makes far fewer mistakes than Walker, whose mistakes came almost to define him. Jacques can talk a good race then, but can he write about one? Yes he can, and this book’s collection of 75 Milestone Moments offers a good précis of the Formula’s history, especially for youngsters who follow the sport with the manic fandom usually reserved for K Pop bands. Looking for a Christmas gift for a Drive to Survive guy or (increasingly) gal? This’ll fit the bill.

The book’s 75 chapters begin with Formula One’s creation in 1950 and end (bizarrely, I thought) with Lewis Hamilton’s move to Ferrari for the 2025 season. (At the time of publication that season is obviously still in full swing.) Alex Jacques is Gen Y, half the age of his subject, and I had feared there’d be too much emphasis on the recent past. Choosing (only) 75 of the sport’s “most iconic stories and moments” is a tough gig, especially in an era when a driver’s most casual obiter dicta can set social media aflame, so I was impressed that we’d reached chapter 34 before the author was even born.

But it’s inevitable that seasoned followers of the sport will raise an eyebrow at the inclusion of some episodes at the expense of others. Nobody will quibble at the importance of the deaths of Jim Clark and Ayrton Senna, nor of “The Yellow Teapot – Renault Build a Formula One Engine” and “Brawn’s Two Titles – Born in Translation”*. But half a chapter on how Valentino Rossi didn’t ever get to drive in Formula One? Or “The Shootout that Made Jenson Button’s Career” or “Multi 2, Seb . . . Multi 21”? I don’t think so, and I guess I won’t be alone in nominating some more significant episodes. If you’re asking: Fangio’s drive for the ages (Nürburgring 1957), and Italian Grands Prix 1961 and/or 1971 (closest finish in F1 history, and last use of the Monza banking respectively, as well as Von Trips’ death which killed 15 spectators). There’s more too, such as the British Grand Prix 1976 (the spectator riot at James Hunt’s exclusion, surely a prequel of toxic fandom) and The Return to Power in 1966 (just imagine doubling the capacity and power of F1 cars in 2025).

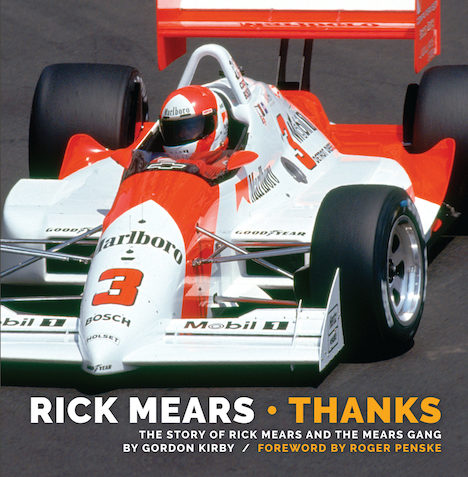

The book is written in an engagingly accessible style, but as the chapters begin to cover races that the author attended there is both personal insight and increased granularity. It’s still essentially a primer for the newly converted, and readers wanting more than five pages on Bernie Ecclestone or Stirling Moss must look elsewhere. For readers interested in the wider world of motorsport, they might also repurpose Rudyard Kipling’s words and ask “what do they know of Formula One, who only Formula One know?” I might even suggest that it’s a tad Eurocentric to discuss Renault’s “pioneering” use of turbocharging in 1977 without mentioning the fact that almost a decade earlier, Bobby Unser had won the Indy 500 in a car powered by the Offenhauser turbocharged four.

The book is written in an engagingly accessible style, but as the chapters begin to cover races that the author attended there is both personal insight and increased granularity. It’s still essentially a primer for the newly converted, and readers wanting more than five pages on Bernie Ecclestone or Stirling Moss must look elsewhere. For readers interested in the wider world of motorsport, they might also repurpose Rudyard Kipling’s words and ask “what do they know of Formula One, who only Formula One know?” I might even suggest that it’s a tad Eurocentric to discuss Renault’s “pioneering” use of turbocharging in 1977 without mentioning the fact that almost a decade earlier, Bobby Unser had won the Indy 500 in a car powered by the Offenhauser turbocharged four.

Although I was already aware of most of the “milestone moments,” one chapter really brought me up short. Did I realize how important the 2010 Canadian Grand Prix had been but have since forgotten? The author entitles chapter 61 as “A Crazy Bridgestone Race Defines an Entire Era”—and it’s not hyperbole. Just in case you too had forgotten (as if), this was the chaotic Canadian Grand Prix in 2010 that “continues to have ramifications for how the driver operates in races to this day.” Tire degradation and how drivers and teams managed it to strategic advantage produced a TV spectacle that formed the template for future seasons. Pirelli said “We can happily make a tyre that would last the whole race, but we need to balance that with a good show.”And if Bernie Ecclestone liked one thing (apart from money) it was a good show, even if diehards think that tires that wear out in minutes create a pantomime. The author shows fine judgment in highlighting this pivotal day at Montreal.

But I think he could have made even more of a point about the significance of Nico Rosberg. I don’t think it was his retirement (“unexpected and left fans and insiders astonished”) that was the biggest story of 2016. I think the real legacy of that year is evidenced in the fact that Lewis Hamilton went on to win another four championships! And a major factor in doing so was his increased mental resilience following defeat by his upstart teammate. Hamilton was the better driver—just—but it was Rosberg, the smartass’s smartass, who knew exactly how to get under his opponent’s skin. Not convinced? Just listen to Nico speak, because he’s one of the very few drivers who can play mind games with battle-scarred F1 journalists and win. Nobody talked much about driver psychology before Rosberg showed that mental warfare was as important as pit stop strategy. But a decade later it’s not unusual for younger drivers to sound as woo-woo as Gwyneth Paltrow about their mental health. Although I bet that’s not something that makes Fernando Alonso lose much sleep.

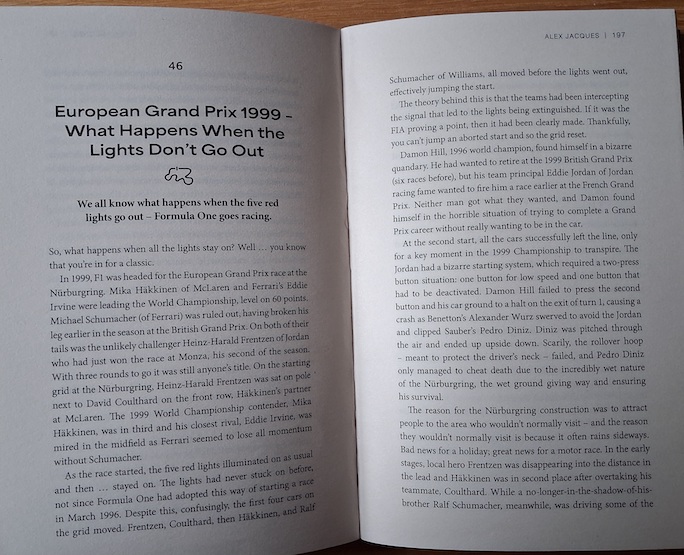

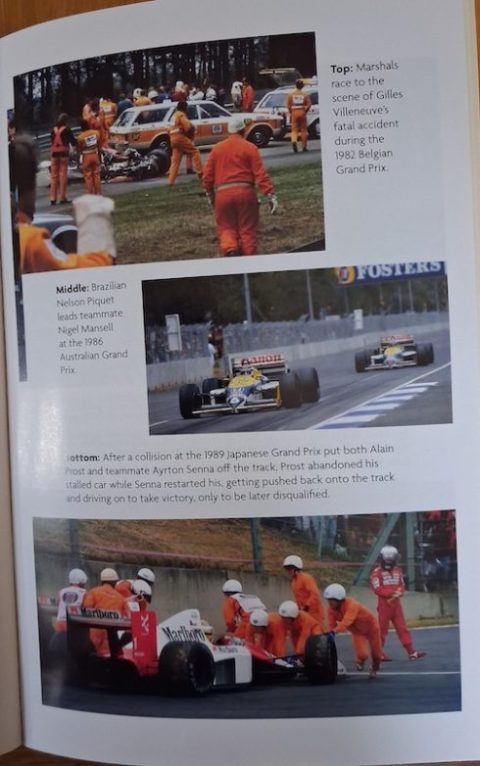

The book has a short section of photographs that are unremarkable, no surprise in such a modestly priced work. The inclusion of Steve McQueen, presumably on the grounds that he didn’t make a Formula One movie, was a surprise though. There are some errors too: Hesketh fielded their own car in 1974 not ’75, and Max Verstappen’s debut didn’t “shatter all precedent” because Kimi Räikkönen’s first Grand Prix had come after just 23 car races, four fewer than Max. And while I can forgive Jacques’ occasionally wayward spelling, his typos should have been picked up by the copyeditor. Such as? Didier Peroni, Roberto Morero, Donnington Park, “breaking (not “braking”) point” and garage-ista (for garagista, Enzo Ferrari’s dismissive term for teams that didn’t make their own engine). Lella Lombardi was christened by the UK press the “Tigress of Turin” not Tivoli, and it’s not strictly accurate to suggest she was “a member of the LGBT+ community” because that implies a degree of inclusivity that simply didn’t exist in the Seventies. In common with fellow F1 driver Mike Beuttler, Lombardi’s sexual orientation wasn’t publicly discussed in the era, other than by oblique reference to “lifestyle.” As for “grizzly 1970s safety standards,”grizzlies are the bad guys who notoriously s**t in the woods . . .

The book isn’t meant to be the last word on Formula One but for newcomers to the sport it’s an endearingly readable first word, written by a young author whose enthusiasm seasons the text. A book spanning three quarters of a century of Formula One risks being superficial, and it’s also a challenge to avoid condescending to its readership. That it has succeeded in navigating around both risks is to Alex Jacques’ credit. I bet he’s already planning the next edition for 2050, working title 100 Milestone Moments. There’s plenty of time to reserve the services of a more diligent copy editor.

- Masayuki Minagawa was the Honda junior aerodynamicist who spotted the loophole in the regulations that led to the double diffuser that was the sine qua non of Brawn F1’s success.

Copyright 2025, John Aston (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter