Engines of Change: A History of the American Dream in Fifteen Cars

by Paul Ingrassia

by Paul Ingrassia

Don’t Get Me Wrong. I Enjoyed This Book. It Just Annoyed the Hell Out of Me.

Ingrassia’s Engines of Change is a lively and intriguing car trip. But contrary to expectations, he’s chosen not to write about cars but about culture. His aim, he says in the book’s introduction is to write “a history of modern American culture in 15 cars.” That may be possible. But a dyed-in-the-wool car enthusiast has come to the wrong place.

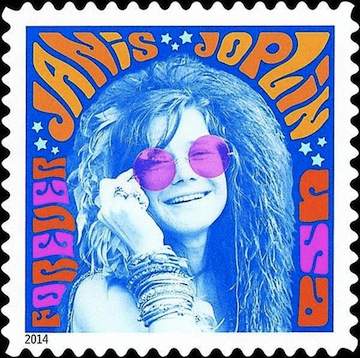

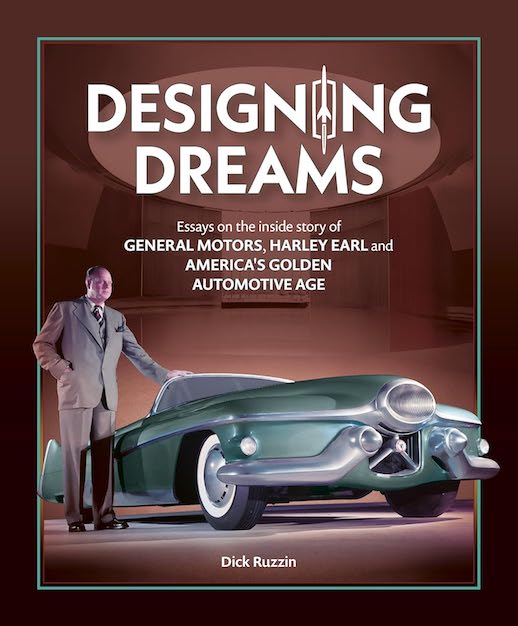

When Ingrassia begins building causal links between cars and social trends most “car guys” are going to come unglued. (There are also some peculiarities on the technical front.) Did the Model T Ford cause the great migration from America’s countryside to our cities, between 1900 and 1925? Or was the Model T the beneficiary of larger cultural forces? Did the 1927 LaSalle really mark a cultural watershed or was it simply a practical reflection of Alfred P. Sloan’s grand marketing plan for General Motors? (He’d brought Harley Earl from California to design the car, and then set up Detroit’s first styling studio).

Ingrassia calls that first LaSalle one of the “the handful of cars in American history that . . . defined large swaths of American culture, helped to shape its era, and uniquely reflect the spirit of its age . . .” But some would argue, it was simply one of a quartet of “companion cars” introduced in the late 1920s in an attempt to slice GM’s market segmentation bologna a little thinner.

Enthusiasts will also notice some lazy fact checking here. Pontiac was introduced in 1926 not 1924. Chryslers of the 1955 and 1957 model years are confused. The 1955 Chevrolet had a flat, Ferrari-like egg-crate grille not a “toothy” front grille. (For toothy grilles try DeSoto). And the ‘27 LaSalle was definitely not “the first car designed by the legendary Harley Earl” who’d become famous at Murphy Body Co. designing cars for Hollywood stars.

In his introduction Ingrassia hardly pays attention to the first 50 years of the industry except for the Ford and the LaSalle. They, he says “are the only pre-World War II cars in this book because American cultural evolution hit a road-block in the 1930’s and 1940’s”—a point of view that would surprise most cultural historians, and a great many poets, writers, film makers, artists and inventors who flourished during that Depression decade! John Steinbeck and George S. Kaufmann come to mind. Likewise publisher Henry Luce, who after successfully introducing TIME in the mid-twenties, brought us FORTUNE in 1932 and LIFE in 1936. Designers like Gordon Buehrig, Raymond Lowey, Walter Dorwin Teague, Harley Earl, and Norman Bel Geddes who designed the GM Motorama for the 1939 New York World’s Fair flourished. The men who built the Empire State building, the Golden Gate Bridge, Boulder Dam, and the legions of others who literally changed the face of America between 1930 and 1940 can’t be forgotten, either.

Engines of Change, however, suggests that with the exception of the Ford and LaSalle, the cars that became cultural mileposts were built after 1950 and are emblematic of the fact that “modern American culture is basically a big tug of war . . . between the practical and the pretentious.” As if this hadn’t been true for the previous 50 years.

The salvation of Engines of Change is the author’s very readable story-telling, fortified by his long involvement with the industry as an automotive journalist. He is currently the deputy editor-in-chief of Reuters. With Wall Street Journal colleague Joseph White he won a Pulitzer Prize in 1993 for “often exclusive coverage of General Motors‘ management turmoil.” He has written two other books on the automobile industry—Crash Course: The American Automobile Industry’s Road from Glory to Disaster (2010) and Comeback – The Fall and Rise of the American Automobile Industry (1995), both still in print. He has appeared on TV and in panel discussions as an expert on the industry. He was born in 1950.

The author’s one concession to the time before 1950 is the first chapter, which he has devoted to Henry Ford, the Model T, and Harley Earl’s arrival at GM. In succeeding chapters he cites automotive highlights of the last half of the last century; Zora Arkus Duntov who saved the Corvette in much the same way that Earl had saved the LaSalle 20 years earlier; tail fins of the 1950s from Cadillac to Chrysler and back; the VW Beetle phenomenon; Ralph Nader vs. innovation, a.k.a. the Corvair; how the Ford Falcon became the Mustang; how John DeLorean bent GM’s rules to come up with Pontiac’s GTO; how Honda quietly invaded Ohio; the invention of the minivan, the SUV, and the pickup truck; the BMW 3 series and the yuppiefication of America; and how the green movement supported Toyota’s Prius and vice-versa—cars that he believes defined American culture.

The stories are engaging and worth the reader’s time. You can take the pop-psychology or leave it. Appended are chapter notes, a bibliography and a very helpful index. The 32 pages of pictures are bundled into two stand-alone sections. Reviews in The New York Times, The Wall St. Journal, and elsewhere have been positive.

Copyright 2013, Arthur Einstein (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter