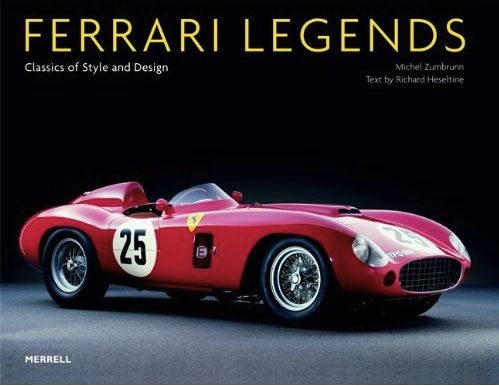

Ferrari Legends: Classics of Style and Design

photos by Michel Zumbrunn, text by Richard Heseltine

photos by Michel Zumbrunn, text by Richard Heseltine

“With Ferrari it is all too difficult to distinguish between the actual and the apocryphal. No other marque has garnered a larger, more adoring retinue, one whose devotion borders on religious fervour.”

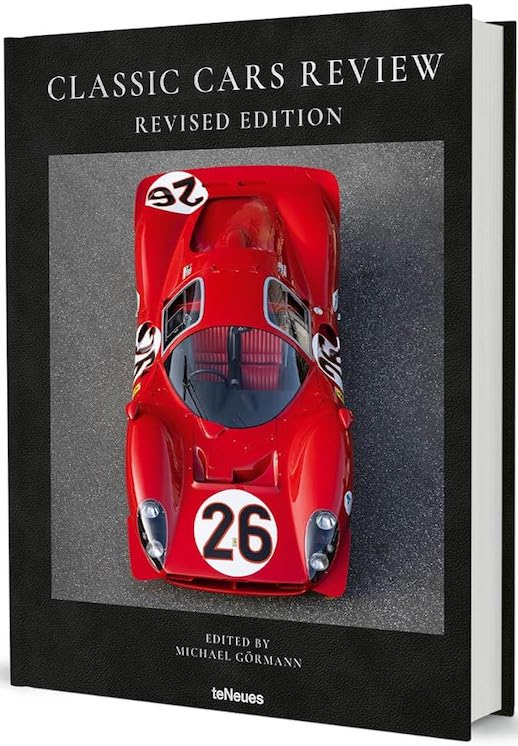

Forty “milestone” Ferraris between 1947 (166 Spider Corsa) and 2002 (Enzo) are culled from the rich palette of road, racing, and prototype cars and presented here for your consideration. Obviously there are other important Ferraris before and after those years the editor chose to focus on—and even within that range (the majority are pre-1970)—but the tug of war over what to include and what to exclude is always present, and always pointless, in compilation books such as this.

This book was the third of now four in a series begun in 2004 (Auto Legends, British Auto Legends, Italian Auto Legends, and American Auto Legends). All but the last were photographed by Michel Zumbrunn. And while the photos do take pride of place in all the books it should be said right away that the publisher avoided the trap so many of this type of book fall into: making one component a mere vehicle for the other; in other words, a photo book in which the text is a mere afterthought or vice versa. Heseltine’s text is perfectly competent, but, with no disparagement intended, without the photos the book would not stand out.

With a byline like Zumbrunn’s it is a given that the photos are technically sophisticated and esthetically sound. An acclaimed studio photographer—who almost became an architect—he had already racked up 20 years behind the lens before his work made a name for himself in car photography, especially in the pages of the famous French magazine Automobiles Classiques which has featured his photos in over 130 editions from 1983 until today. “Studio” doesn’t mean he doesn’t go on location but that wherever he goes he creates a “box” (ca. 30 x 50 x 10 ft) in which to create controlled conditions to work his magic. Often enough though, clients who think only he can do their cars justice go to the trouble of shipping them to his studio near Zurich. The main purpose for this lengthy explanation is to establish that the photos in this book are not all specifically made for it but are selected from an existing collection. (It also means that Zumbrunn most likely had nothing to do with either selection of specific shots or the choice of cars.)

The general viewer would not know that the cars were shot at different times and places because all are photographed against a black background and on a grey, textured, unreflective surface. Speaking of reflections, the more photographically minded viewer cannot fail but notice that those interior shots that include any window glass will inevitably show the interior being reflected in the glass, an effect not helped by the black backdrop. Since the photos are taken over a period of time, in which the photographer’s skill and equipment changed, the viewer is left to wonder if the most drastic example of this (p. 101) is intentional “art” or from “the early phase.” (If you have the fourth book in this series you’ll notice that photographer Michael Furman does not use any such photos; surely no coincidence.) Most photos are of the whole car, from different angles, several taking full advantage of the landscape format’s 25” width when open. All, even the detail shots, are, for lack of a better word, “clinically correct”—no unusual perspectives or extreme close-ups. This is a conscious choice, not lack of creativity: Zumbrunn wants to enable the viewer to recognize and place everything he is shown. (If it matters to anyone, one car is not in standard factory trim and one is a replica.)

On the writing side, Heseltine’s 20-page Introduction deftly paints a cohesive picture of Ferrari highlights. Enzo’s early interests in becoming an opera singer or journalist being thwarted by lack of talent, his first automobile job test driving Lancia trucks converted to road cars, racing, wives, children, ups, downs, customers, wars, money, Ford—colorful, nuanced, human. Enzo Ferrari is an archetypal example of the connection between the characteristics of the maker and that which he makes. This section of the book is the only one to use archival period photos.

In chronological order each of the 40 cars is described on 6 to 8 pages, half of which photos. The photo captions are detailed and—sounds obvious but isn’t—specific to the photos. Heseltine (whose name you will recognize as a contributor to all sorts of motoring publications) has a really good handle on saying just enough to bring out each car’s specific attributes, its virtues and vices and overall place in the Ferrari pantheon. Useful information is given about the coachwork which, in the early cars especially, is a key aspect of their allure.

As all books in this series, it concludes with a collection of mini bios of designers and race drivers, a glossary, a museum directory, and an Index—and it doesn’t list the cars in the Table of Contents but only in the Index, and there only by model name and not year. The latter requires the reader to be already familiar with the subject in order to put it to good use.

All the books are also available in unabridged softcover editions but unless you are on a severe budget, get the hardcovers. These are substantial books with good, heavy paper that is simply too much for a flimsy softcover. Moreover, only a hardcover binding can have a properly rounded spine, making the book much more stable and durable.

Copyright 2010, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter