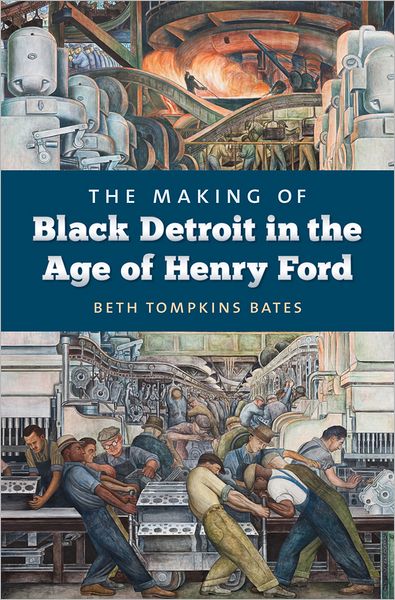

The Making of Black Detroit in the Age of Henry Ford

“The initial bond between Henry Ford, black Ford workers, and the black community was tied to their mutual aspirations. Ford expected loyalty and allegiance from his black workers as well as the larger community, thus reducing the threat of unionism. African Americans were anxious to prove that they were worthy of inclusion in Henry Ford’s new-age industrial jobs, demonstrating their allegiance to both Ford and the American Way.”

That small word “initial” can mean only one thing: the honeymoon didn’t last. Henry Ford was 39 years old when he founded the Ford Motor Company. He was neither a young whippersnapper who saw the world through rose-colored glasses nor so old as to be set in his ways. He changed—everything. For a while.

So you know all about that alphabet soup of early Fords, the S, T, N, A. But what about the Ford Hunger March, aka the Ford Massacre? Sinister, eh? The history of the automobile is inseparable from the history of the people who make it. And labor history means union history. And union history means . . . well, all that is covered in this book.

Bates explores this subject as a professional historian (Wayne State University in Detroit) and devoted an earlier book to its railroad angle, Pullman Porters and the Rise of Protest Politics in Black America, 1925–1945. This new book examines individuals and communities, economic theory and political reality, tangible pros and cons, the Ku Klux Klan’s (so much for only having influence in the South!) anti-black and also anti-Catholic position, the Communist Party USA. It is an engaging book, lucidly presented and approachable to anyone with a curious mind. But it is not an easy subject to get into because it introduces so, so many strands that the general-interest reader may be only vaguely familiar with. Bates herself was surprised to discover that black Detroit did not remain docile, did not simply roll over and play dead when the strained alliance between blacks and Henry Ford unraveled, a notion all the more remarkable in view of the fact that the city’s black population had swelled by 600% between 1910–20.

The US civil rights movement is a divisive subject at the best of times, even when approached with academic detachment. While it is a uniquely American topic there is a global precursor in the form of European immigration being reduced by some 90% in the aftermath of WW I and also the 1917 Russian Revolution that made US corporate leaders across the board fearful of workers’ rights and emancipation.

A look at the extensive Bibliography Bates furnishes confirms just how well explored a subject this already is but her focus on this part of the timeline fills a void. The book offers a clear and compelling account of Ford’s motives for courting blacks, their initially shared anti-union sentiments, and blacks’ subsequent shifting allegiance when Ford’s progressive impulse waned or became diluted by other concerns, reducing them to “Ford mules” shut out from the American Dream. This is a chapter of American history Ford changed, but inadvertently!

Copyright 2013, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter