Formula 1 Car By Car 2000–09

by Peter Higham

by Peter Higham

“Give me a few bits of wool to stick on the car, a good gust of Mistral wind, and I could come up with a better aerodynamic package on the bridge at Avignon than the team has managed.”

—Jean Alesi, on the Prost Ap-03 Peugeot

It’s testament to my own advancing years that my first thought on this book was that it was about the very recent past. But I was reminded quickly that the earlier seasons it describes happened almost a quarter of a century ago. Pre 9/11, pre social media, pre Liberty Media and Drive to Survive, the time when dinosaurs still ruled the sport and only birds tweeted. This highly detailed book reminded me that even a year can feel like an aeon in Formula 1, such is the pace of development and the incidence of change.

This 304-page work is the latest in Peter Higham’s reviews of decades in Formula 1, covering the periods starting in 1960. Perhaps the changes seen in earlier decades—the move from front to rear engines, the exploitation of aerodynamics, and the advent of turbocharging—were more profound, but 2000–09 was hardly uneventful. There was no lack of surprise, innovation or excitement and, thanks to Brawn GP, there was a fairy tale ending. Even the soundtrack changed, from that wonderful doomy howl of the V10 to the hysterical scream of the little 2.4L V8.

This well-illustrated book is a dispassionate, season by season, team by team analysis with a short introduction about the year in question. Equal importance is attached to every team, and every driver who competed is mentioned in the summary of a season’s results which concludes each chapter. This distinguishes the book from many others in the field, not to mention most modern media coverage of the sport where the contemporary stye of reportage is to focus exclusively on the so-called “battle” for the title between the two or three leading drivers, increasingly sprinkled with gossip, scandal, and showbiz glitz. But if it’s the sport that interests you (as it does this reviewer) then it’s just as important, and often more interesting, to focus on the also-rans and failures, the dreamers and the carpetbaggers. The current homogenized version of the sport has begun to operate almost as a cartel—you can ask the Andretti family about that—but the early 2000s had no shortage of chancers and terminal tailenders.

This well-illustrated book is a dispassionate, season by season, team by team analysis with a short introduction about the year in question. Equal importance is attached to every team, and every driver who competed is mentioned in the summary of a season’s results which concludes each chapter. This distinguishes the book from many others in the field, not to mention most modern media coverage of the sport where the contemporary stye of reportage is to focus exclusively on the so-called “battle” for the title between the two or three leading drivers, increasingly sprinkled with gossip, scandal, and showbiz glitz. But if it’s the sport that interests you (as it does this reviewer) then it’s just as important, and often more interesting, to focus on the also-rans and failures, the dreamers and the carpetbaggers. The current homogenized version of the sport has begun to operate almost as a cartel—you can ask the Andretti family about that—but the early 2000s had no shortage of chancers and terminal tailenders.

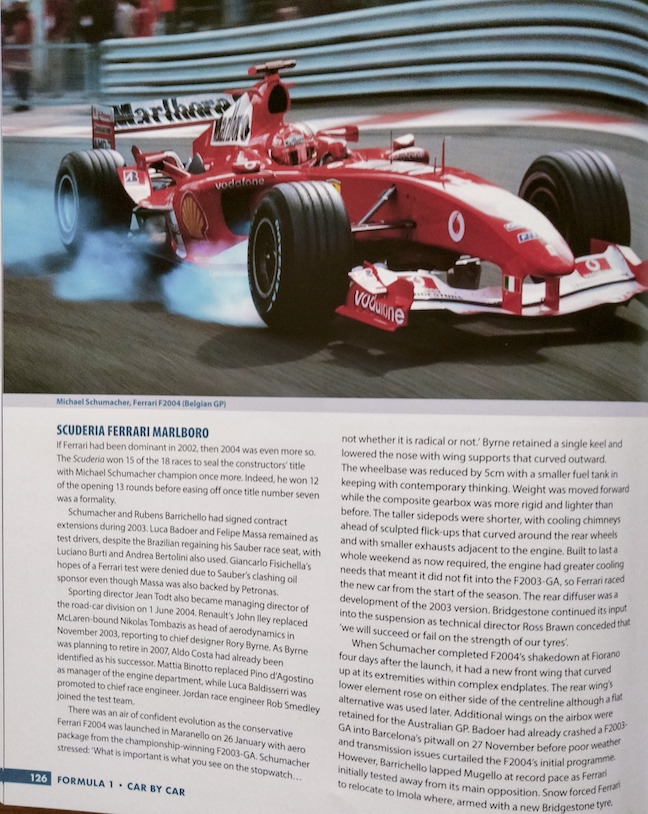

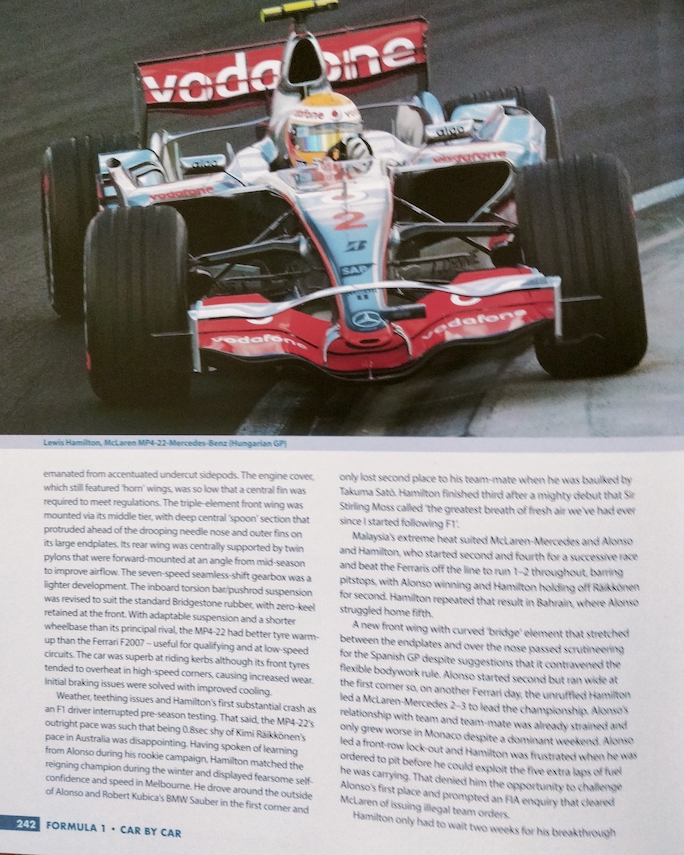

The reader can almost sense the movement of Formula 1’s tectonic plates with the passage of each season. Ferrari and Schumacher dominated the early years of the decade but ended it trying, and failing to keep up with the parvenus at Red Bull and their old foe McLaren. We witness the meteoric debut of Fernando Alonso and his rapid ascent to double champion, before reminding ourselves that, almost unbelievably, this toughest of tough guys is still at the sharp end of the grid. Never mind that he’s the oldest driver. There’s the slow decline of Williams after its marriage with BMW hit the rocks and, perhaps most notably of all, there is the extraordinary debut of Formula 1’s winningest driver, Lewis Hamilton, in 2007.

The reader can almost sense the movement of Formula 1’s tectonic plates with the passage of each season. Ferrari and Schumacher dominated the early years of the decade but ended it trying, and failing to keep up with the parvenus at Red Bull and their old foe McLaren. We witness the meteoric debut of Fernando Alonso and his rapid ascent to double champion, before reminding ourselves that, almost unbelievably, this toughest of tough guys is still at the sharp end of the grid. Never mind that he’s the oldest driver. There’s the slow decline of Williams after its marriage with BMW hit the rocks and, perhaps most notably of all, there is the extraordinary debut of Formula 1’s winningest driver, Lewis Hamilton, in 2007.

Even though I follow Formula 1 with the same diligence as I did when Damon Hill’s dad was driving for Lotus, this book both rekindled memories and reminded me of what I had forgotten. I will confess not to have devoted too much thought of late to drivers like Gaston Mazzacane (Minardi, 2000), Zsolt Baumgartner (Jordan 2003), and Sakon Yamamoto (Super Aguri 2006). And how had I almost forgotten what a furore Kimi Räikkönen caused on his signing with Sauber in 2001? It’s not unusual now for a teenager to drive in Formula 1 but Kimi’s “youth”—21—and inexperience—23 car races—had furrowed many brows. As an aside, checking my program collection (yes, I know) confirms that I had even witnessed one of Kimi’s wins in Formula Renault at my local circuit in the north of England.

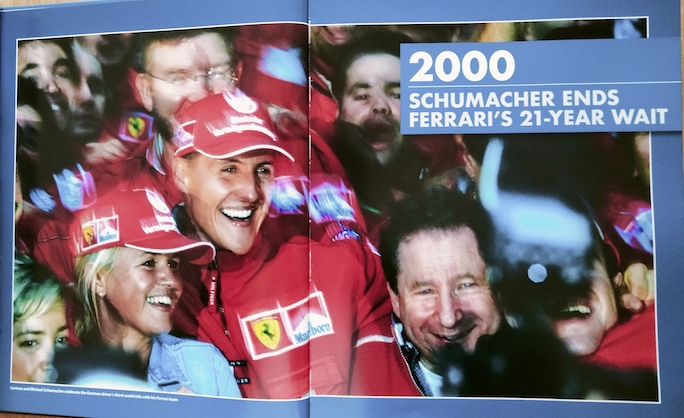

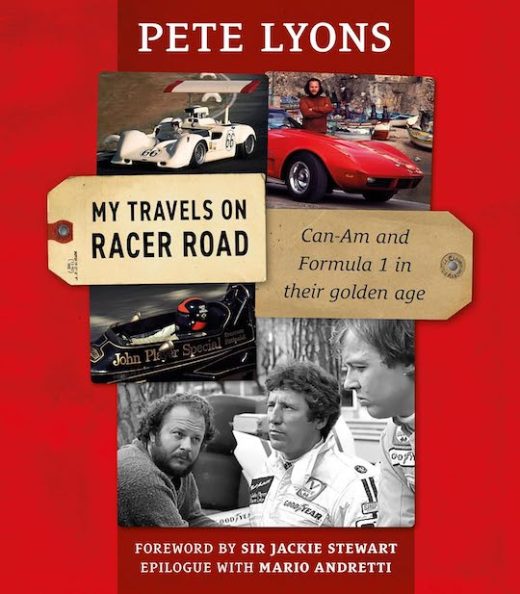

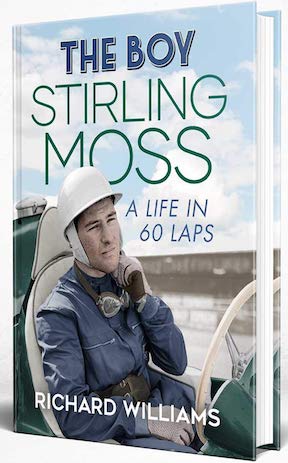

This is not a book you should read over a couple of rainy afternoons, as I did. It’s not a page turner and, if it had been, its status as a no-nonsense book of record would have been diminished. There’s none of the gossip or intrigue a new fan of the sport might demand, and that is to be welcomed. Instead, there’s a detailed and properly researched account of each season, starting with winners and descending to the losers. There are no spurious statistics, and we are spared the silly GOAT musings that are responsible for the sport’s current white noise mood music. It’s possible to have too much information and the skill the author displays is in condensing the story of each season into 30 pages, ending with a two-page summary of results, by team and driver. The pictures enhance the account and perhaps none is as poignant as the image that prefaces the first chapter. It depicts a deliriously happy Michael Schumacher, his wife Corinna, Ross Brawn, and Jean Todt (below).

The passage of a couple of decades can bring sharper perspective. I found myself musing why F1 liveries are now such a mess compared to the strikingly elegant color scheme sported by the Williams BMW in 2000, and I wondered whether Jaguar and BAR’s hubris was as obvious then as it clearly is today. And how deliciously ironic it is that these two teams would come to dominate F1 a decade later, albeit rebranded as Red Bull and Mercedes. Further, while Messrs Wolff and Horner are the pantomime villains of today, their spats and posturing seem playground stuff compared to the Machiavellian plotting indulged in by (inter alios) Messrs Ecclestone, Walkinshaw, Dennis, Jordan, and Briatore. The Piranha Club made flesh . . .

We can only understand modern Formula 1 through an awareness of its past. Peter Higham is to be congratulated for enabling the reader to grasp how and why the sport has evolved by this expertly written and researched account of the sport’s progress in the first decade of the new century.

Copyright John Aston, 2024 (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter