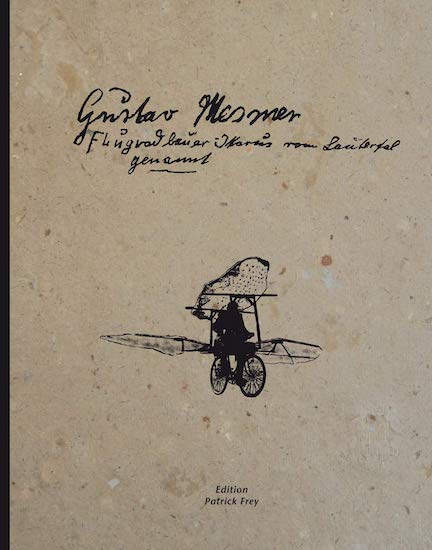

Gustav Mesmer, Flugradbauer

Ikarus vom Lautertal genannt

“The fact that it is possible for such a creative person to spend almost half his life locked up in a psychiatric hospital makes me want to cry more than write. It is horrifying how narrow social norms are, and how little tolerated outside the mainstream—and how potentially dangerous that is.”

(German, English, French) The Mesmer (Franz Friedrich Anton) to whom we owe the word mesmerized is not the one of this book (Gustav), but transfixed you will be, by Gustav M.’s existential struggle with life, by his afflictions, choices, and passion for invention.

That not more of him is known, even in his native Germany where pretty much everybody knows a pioneer of human-powered flight such as Otto Lilienthal, can probably only be explained by the fact that Mesmer lived so on the fringes of life and art and sanity. A book review cannot be the place to really move that needle, so all we can do is recommend this fine book—warmly. You only have to consider the title of Mesmer’s 1962 autobiography to fathom what a tortured soul he was: Of One Who Spent Part of His Life in a Monastery and Part in a Psychiatric Institution.

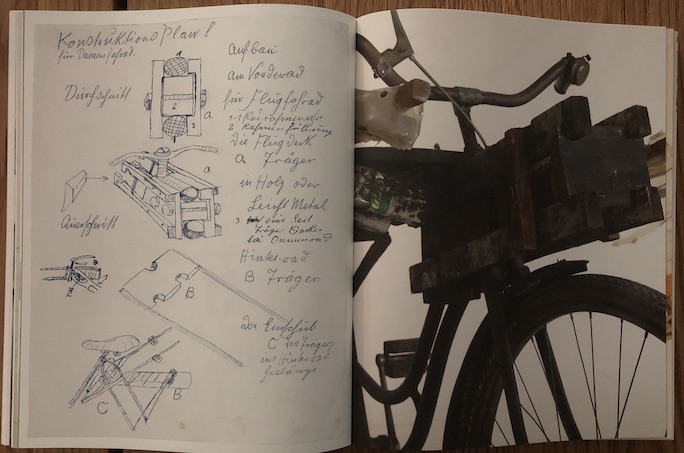

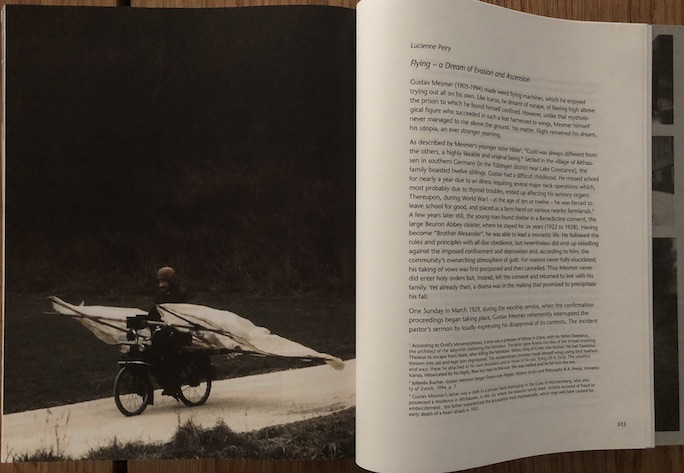

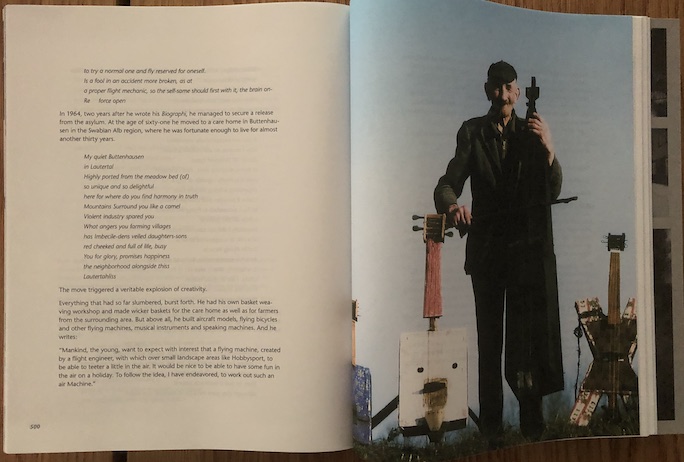

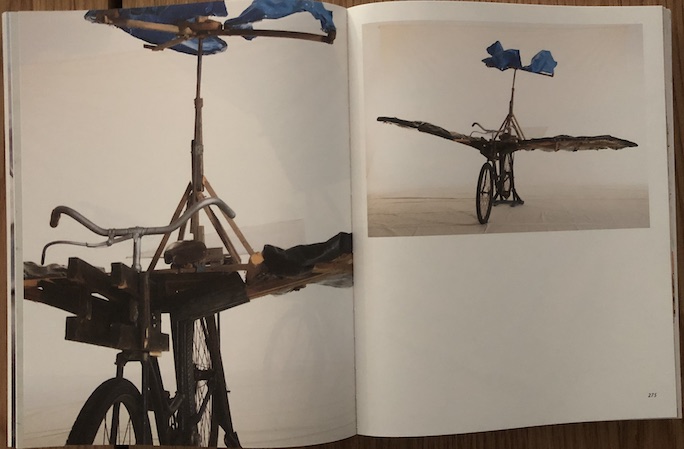

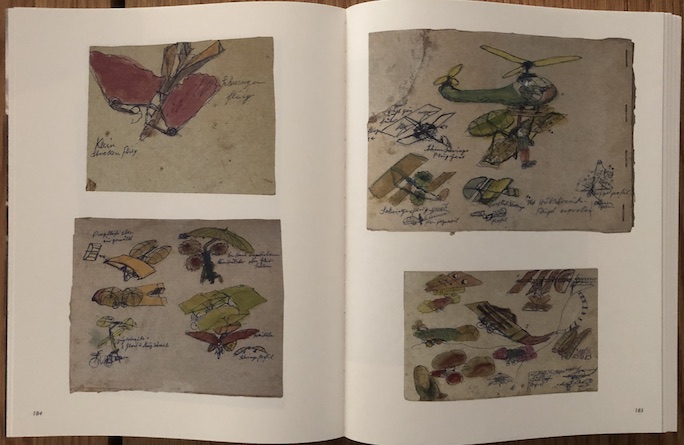

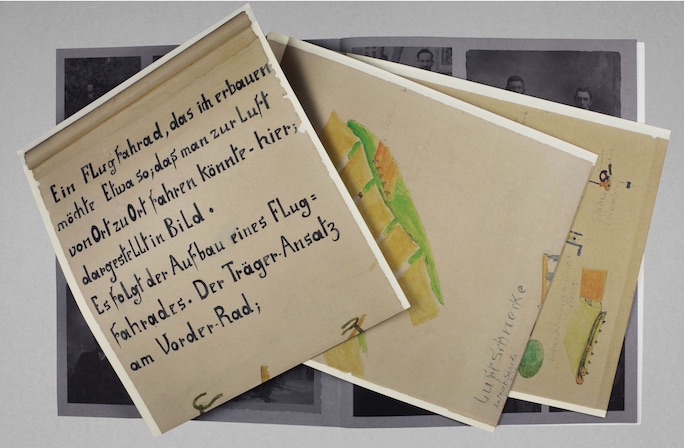

Why are we interested in him? Because he wanted to fly—using a bicycle for power! He made drawings, he made scale models, he built full-size versions and tested them himself. Seeing an old man careen down steep hills trying to get lift under his wings was a familiar local sight (he died in 1994, just shy of his 92nd birthday). He tried a bicycle helicopter. He tried shoulder harnesses. Birds small and large have them so why did God not give Man, the crown of creation, wings? He claimed to actually have achieved flight for 50 yards—alas, without any witnesses. “The Flying Bicycle Builder-Icarus of Lautertal,” (the Lauter valley in Germany’s Swabian Alps) took his ideas very seriously. So did—a few—proper scientists who were intrigued by his theory that piercing numerous holes into the wings or sails of his contraptions would improve their aerodynamics.

Mesmer tinkered with much more than bicycles and flying (musical instruments, various crafts, words). Even during his lifetime there have been exhibitions in Europe of his “outsider art,” a bicycle of his was shown in the German pavilion at the 1992 World Exhibition in Seville, short films of his work have been made (1981, 2000) but English-speaking readers have probably never heard of the man.

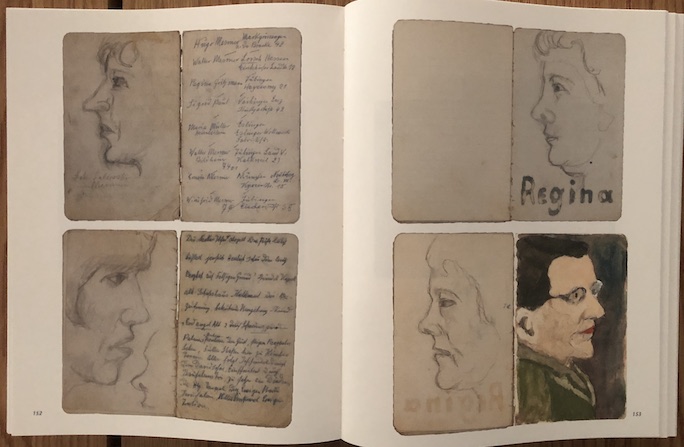

Unless you’re made of stone, this book (which also has serious bibliophile bona fides) cannot fail to move you. In his own mind he was a seeker but Mesmer’s family and their doctor stuffed him into a mental institution. He pleaded. He escaped. Repeat. Many times. And just remember the timeline—Nazis (one of his portraits definitely is Hitler), exterminating the unfit, forced sterilizations, gas chambers; Mesmer understood how making himself useful was a little bit of insurance. At one point he had himself transferred on his own initiative to a psychiatric hospital, and would remain there for 15 years (out of some 35 years of his life in institutions) before being released into an old people’s home, at 61 years of age. By this time he had already had flying bicycles on the brain for some 30 years—so he hit the ground, as it were, running.

His story is complicated, complex, quite without parallel. The book is neither biography nor catalog raisonnneé. It shows only Mesmer’s flying apparatus and a few pages of portraits of relatives. That the author is respectful and sympathetic rather than playing up the Don Quixote/Tilting at windmills–aspect is because Hartmaier is a trustee of the Mesmer Foundation. He is also an artist himself and practices in a variety of disciplines, from photography to exhibition displays. Most importantly, he knew Mesmer in his later years. Hartmaier alludes to that in his very sensitive Foreword but even though the book is trilingual, it appears only in German.

The only other text is three essays, in all three languages, in the second half of the book, one each by Lucienne Peiry, Juliane Stiegele and Franz Xaver Ott. All of them have professional or personal points of connection with Mesmer’s life and work and they touch on it in a sort of free-form manner—but no cohesive, chronological or otherwise fully fleshed-out picture of Mesmer emerges. Certainly, nothing is “explained” in any conventional sense. The reader who wishes to know more is left with a relatively short bibliography in which most entries point to general titles on art and psychology.

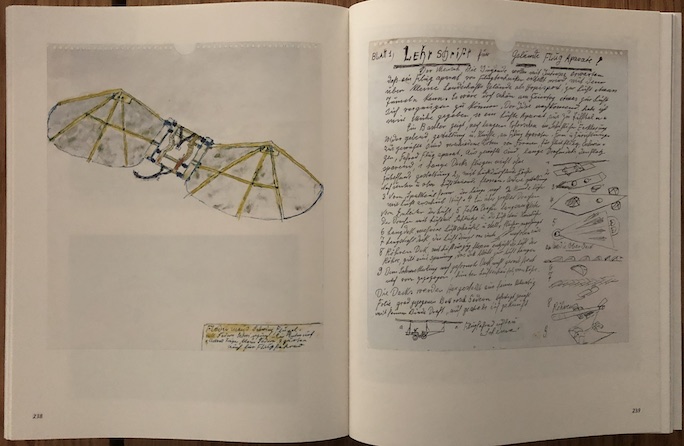

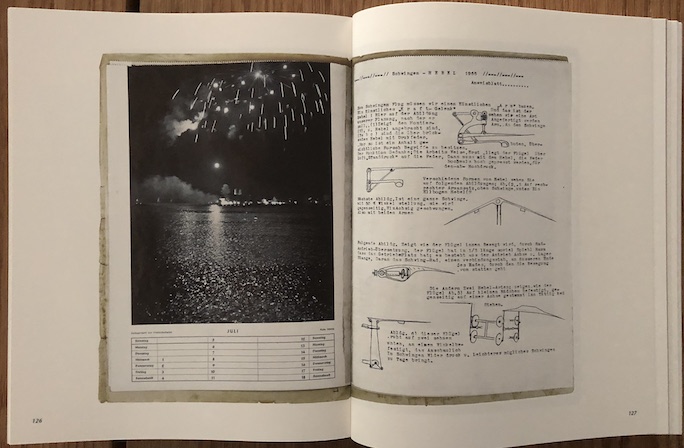

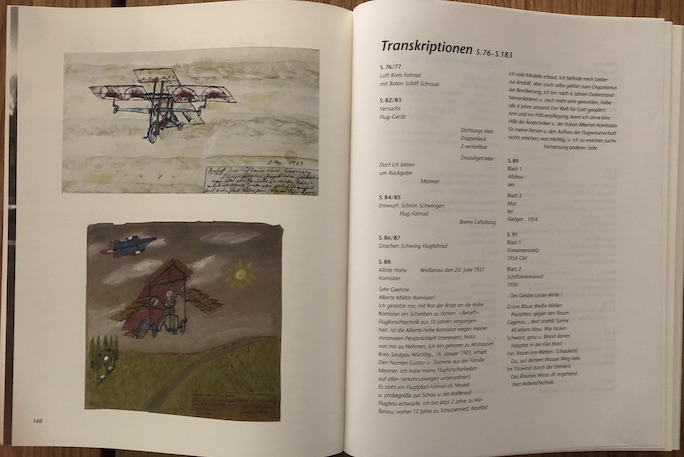

“The reader who wishes to know more” . . . well, that’s the kind of reader every author hopes for but that type of reader will be quite, quite lost here. It gives us no joy to say that this book is infuriating to work with! The first 300 pages are back to back artwork, but nothing is dated or captioned. Every 70-odd pages—not that this is explained anywhere; you either find it and figure it out or you don’t—are sections of several pages (on different paper from the artwork) entitled “Transcriptions” which means they show typeset versions (above; but only in German, even reproducing the misspellings and grammatical glitches of the originals) of the often hard to read handwritten jottings/legends Mesmer added to many of his drawings. These transcriptions refer to the drawings by page number—a perfectly sensible plan, until you notice that not all pages are numbered; and since not all drawings have legends that need transcribing, finding the right page gets even trickier. Then, it is entirely unclear if the drawings are shown in chronological order; example: p. 160 is one of the few that Mesmer dated, 1988 (and that one even shows a jet plane!), and so is p. 188 but does that imply all the ones in between are too?

None of these design choices, it is safe to say, are accidental: this Swiss art publisher is rightly renowned for design-intensive, cerebral books that are as much “art” in their own right as the topics they cover. A particularly noteworthy feature (and surely costly; Hartmaier says a different publisher had asked him to put up 50,000 Euros of his own to get this done) is the insertion of a 12 ft long folded piece of paper, a scaled-down reproduction of a 42 ft long roll of wallpaper on the back (which is also reproduced here) of which Mesmer had sketched a sort of “movie” (below).

So, in terms of concept this really is a special and unique book. The casual page-flipper will be endlessly delighted by the almost 1000 drawings and photos (by Hartmaier and Franco Zehnder) and those who can read German will certainly want to dwell on Mesmer’s actual words. (There are also a few typewritten pages from a 1955 manuscript of Mesmer’s.) Those who do want to know more . . . well, there’s no easy answer here. The (trilingual) Mesmer Foundation website is a starting point but it seems to need a review: one page says Gustav was the 5th of ten children, another the 6th of twelve.

As an aside, that his contemporaries nicknamed Mesmer “Icarus” is really quite the fallacy as Mesmer didn’t have even a smattering of the hubris that took the Icarus of legend down. That Hartmaier and his contributors, not to mention the legions of writers who dip into this topic, do not address such fundamental things does no one a service.

Copyright 2019, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter