The Racing Bicycle: Design, Function, Speed

by Richard Moore, Daniel Benson (Editors)

by Richard Moore, Daniel Benson (Editors)

If you know your bicycling history you’ll wonder why the name Moore sounds familiar. There was a Moore, James Moore (1849–1935) who was a bicycle racer and so good that he won the world’s first road race (Paris–Rouen 1869) and dominated competition for years. No relation to the author though.

If you know your book history you’ll also wonder why the name Moore sounds familiar. Bingo. Same Moore. Same book in fact but the UK edition with a slightly different title and published a few months earlier: Bike! A Tribute to the World’s Greatest Cycling Designers (Aurum Press). While Moore, a long-time cycling journalist and former racer, and Benson, a cycling veteran and managing editor of Cyclingnews.com, could easily have written this book they function here as editors of contributions by 11 mainly UK-based cycling journalists, each of whom penned several of the book’s several dozen entries. On the one hand, since each entry covers one individual maker, this divide-and-conquer approach works fine, in fact it may be desirable inasmuch as it ensures the impartiality one single writer may be incapable of. On the other hand, the absence of any sort of comparative commentary or overarching narrative results in occasional ambiguity regarding certain specifics that one writer weighs differently from another.

If you consider that the state of the art in James Moore’s day was a wooden bike with iron tires inlaid with ball bearings you’ll learn from these pages how unbelievably far we’ve come. The Foreword by Robert Penn speaks to the evolutionary aspect of ever-improving materials and, consequently, architecture and also the highly personal aspect of a supremely specialized and bespoke piece of equipment.

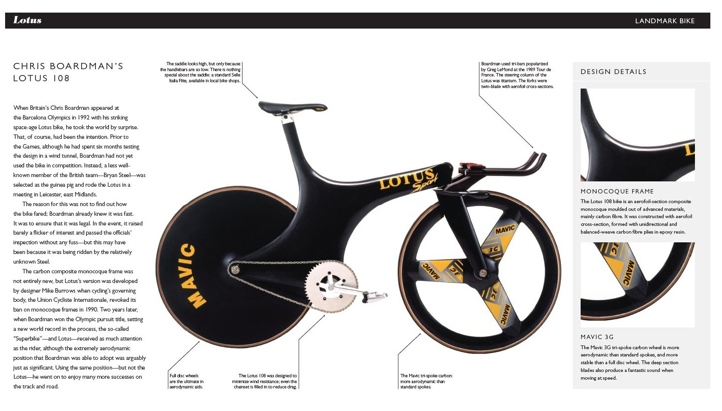

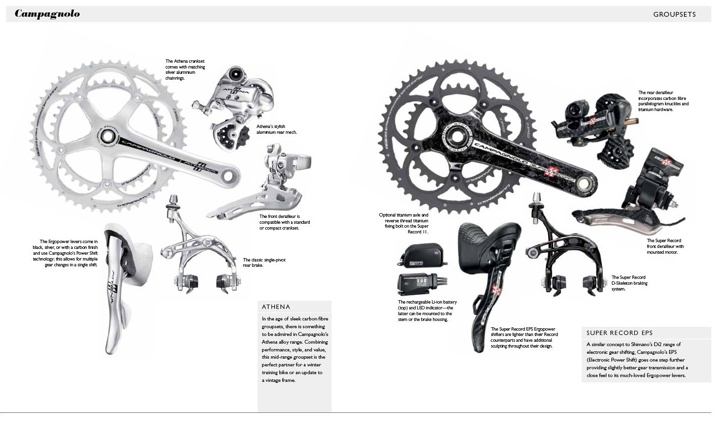

The focus is on racing bikes but there is some attention given to track, cyclo-cross, and mountain bikes. The book’s US subtitle makes even less clear than the UK title that this is not an overall treatment of the history of the racing bicycle but a presentation of 49 of “the world’s greatest” frame and/or component makers big and small in individual entries in alphabetical order, plus another 9 two-page treatments of certain “landmark bikes” and their riders. This symbiotic relationship is actually quite well recognized in the Introduction: “ . . . great riders might be said to have ‘made’ some of the great bikes—or at least endorsed them in the most efficient way, on the greatest stage.” In fact, one of the inescapable conclusions from reading this book is that there aren’t that many fundamental differences among bikes of a certain era and that it is the riders who distinguished them.

Most of the makers considered here are European or American and in explaining the difficulty of choosing whom to include, Moore/Benson make another useful observation: the world of frame building is, sometimes at least, “clandestine.” Meaning you can’t always know who built which frame, making it “difficult to know how much acclaim a particular manufacturer is due.”

The coverage of historical and technical highlights is leavened with anecdotes “that range from the sublime to the ridiculous, with a sprinkling of quirkiness and eccentricity, too.” Presumably each contributor worked independently; absent any editorial intervention this means that there is a certain duplication among entries that becomes readily apparent if you read many back to back. This also accounts for different levels of magnification and even overall appreciation of the sport’s nuances and history, especially in a national context. An example would be commentary about a particular champion’s personality made by different contributors who don’t all see things the same way. While not a surprise in this sort of book it may need to be spelled out anyway, if only to spare the novice in the sport a rude realization: little is said about things that didn’t work, be it on the technical or the people front. And female riders will say that the book is gender biased.

One is inclined to say the editors didn’t so much edit as merely compile.

Still, this is an engaging book of broad scope, most excellently illustrated with hundreds of archival and modern photos (detailed captions, credits are listed at the back), and with enough depth to even tell the old hand something new.

Appended are 1903–2011 Tour de France winners (by year, rider, team, frame, components). This list will need to be amended once Lance Armstrong makes up his mind about his past. Contact info for all makers in the book and weblinks to cycling organizations and e-zines are offered, and there is a Glossary, a very deep Index, and mini bios of the contributors.

A lot of book for the money!

Copyright 2013, Sabu Advani (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter