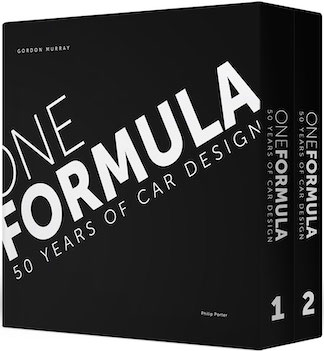

One Formula – 50 Years of Car Design

by Gordon Murray and Philip Porter

by Gordon Murray and Philip Porter

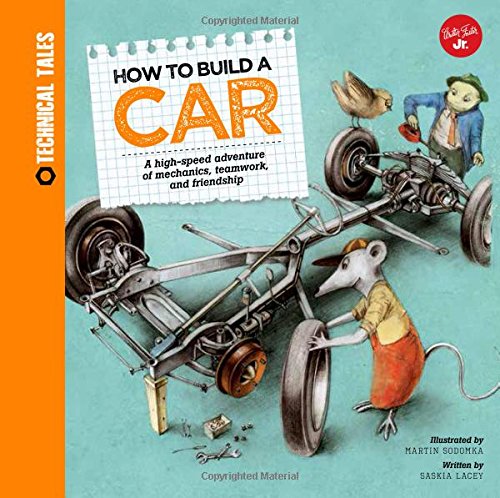

This book is the latest in a series of recent biographies of prominent designers in Grand Prix racing. Following Karl Ludvigsen’s superb Colin Chapman- Inside the Innovator in 2010, Adrian Newey’s How to Build a Car was published in 2017, and John Barnard’s The Perfect Car in 2018. Murray’s book is not a biography in the strict sense as it is primarily about the scores of vehicles he designed between 1967 and 2017, rather than about the man himself. Murray might state in the introduction that the book is “not my life story, but the story of my automotive designs” but so much of Murray the man is exemplified in his designs that the reader will obtain a profound insight into the South African’s own personality. The book takes the straightforward approach of beginning with Murray’s first car design, the Lotus Seven-esque IGM–Ford T1 in 1967. It continues, via his years in Grand Prix racing with Brabham and McLaren, and concludes with the work undertaken by Gordon Murray Design Limited between 2005 and the present day.

This is a massive, two-volume, sixteen chapter work of 948 pages. It features hundreds of reproductions of design drawings, supplemented by photographs (b/w in early years, color later). Nearly all the photographs are high quality, and some of the two-page spreads are simply stunning. Each volume is 12” square and almost 2” thick, and at 8 pounds it weighs so much that it cannot be read in any comfort except when placed on a stand or table. The book is beautifully designed and produced, as the reader should expect at prices ranging from £220 to £2200 ($285–2850) for the most opulent edition. This review relates to the cheapest edition.

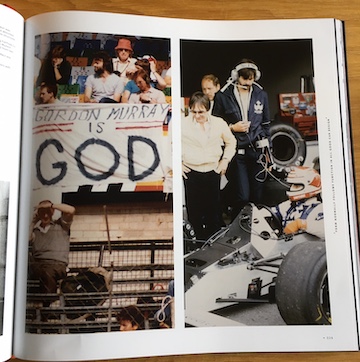

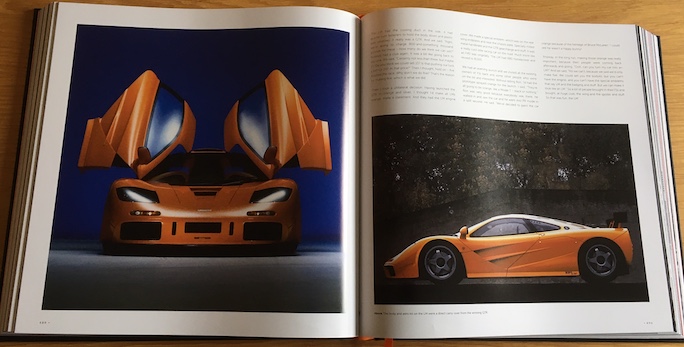

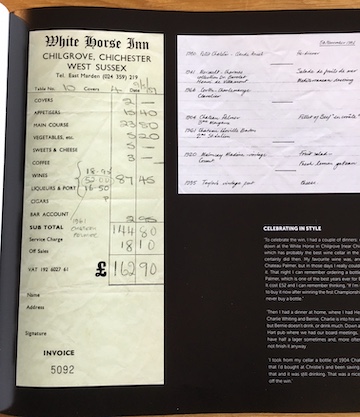

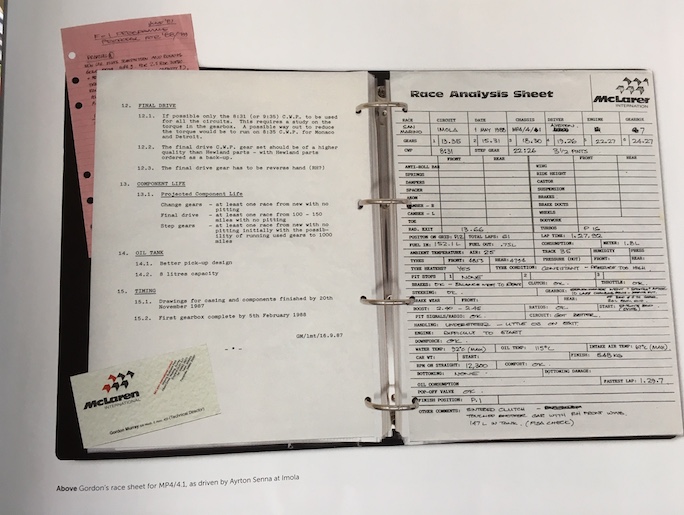

Chapters relate to individual designs and, typically, comprise reproductions of individual design drawings, period photographs with narrative from Murray and Porter, supplemented by short interviews with key colleagues and collaborators, such as Peter Stevens, who was responsible for the styling detail of the original “hypercar,” the McLaren F1. Contributions from other Murray co-workers include those made by well-known industry figures like Jeff Hazell and Neil Oatley. There are also many items of ephemera, such as a note of a bet with Ken Tyrrell and the menu and wine list from the dinner Murray hosted on 5 November 1981 to celebrate Nelson Piquet’s world championship victory for Brabham. It is clear that Murray has retained absolutely everything of interest, no matter how peripheral, relating to his career and passions (which notably include the works of Bob Dylan and Hawaiian shirts). Fascinating though many of the drawings are, the human interest exemplified in the photographs, contributions by co-workers and general minutiae leaven what could otherwise be a heavy read for the less technically minded reader (such as this reviewer).

One Formula is a book that really deserves to be read properly. It should not be devalued by being relegated to coffee table trophy, artfully left open to impress dinner guests with their host’s erudition and good taste. And, when you have finished reading the book, you will reflect not only on the highlights of Murray’s career but also the staggering work ethic he applied in creating up to 500 drawings per car, often to the tightest of deadlines. It is perhaps no wonder he admits, during the difficult gestation of the Brabham BT 50 BMW turbo F1 car, that “I lived on pills and was working 18 hour days.” The term “disruptive,” in its modern sense, was not in use during most of Murray’s career but it perfectly describes the creative genius he applied to produce the infamous Brabham BT46B “Fan Car” in 1978, the first planned use of pit stop refuelling in modern Grand Prix racing at Brands Hatch in 1982 or Murray’s most enduring legacy, the McLaren F1 road car. This is the car whose astonishing performance rewrote the supercar rule book overnight in 1992 and which, 25 years later, sells for up to $20 million at auction. Intriguingly, its 3-seat layout has been an enduring theme since 1969 for Murray and, whilst that was not the ideal layout for racing— which had not been originally even contemplated for the F1—the F1 famously won Le Mans in 1995.

The reader will be left in no doubt that, so far as Formula 1 is concerned, Murray’s salad days were the time he spent in the more laid back atmosphere of the Brabham team than during the far more buttoned down McLaren era, which began at the end of 1986. Brabham boss Bernie Ecclestone was happy to give  Murray virtually carte blanche to achieve racing success, a pragmatic approach given Ecclestone’s increasing role in the marketing and monetization of the sport. Evidences of personality clashes are rare in the book, with the general consensus being that Murray consistently managed to balance the role of inspiring team leader with remaining a decent and likeable man, happy to credit the contributions of people such as US transmission guru Pete Weismann.

Murray virtually carte blanche to achieve racing success, a pragmatic approach given Ecclestone’s increasing role in the marketing and monetization of the sport. Evidences of personality clashes are rare in the book, with the general consensus being that Murray consistently managed to balance the role of inspiring team leader with remaining a decent and likeable man, happy to credit the contributions of people such as US transmission guru Pete Weismann.

However, it is clear that the McLaren era was both the best and the worst of times for Murray. The extraordinary success of the MP4/4, in which Alain Prost and Ayrton Senna won every Grand Prix except one in 1988, was unprecedented in the modern era but the book also recounts the difficult relationships with fellow designer Steve Nichols and team boss Ron Dennis. By the early Nineties Murray’s emphasis had shifted to McLaren road cars but, after the success of the F1, came the far more compromised Mercedes Benz SLR McLaren. The last straw for Murray came when Dennis announced the team’s future alliance with Mercedes, thus derailing another BMW-powered road car project, the McLaren BMW Coupe P2.

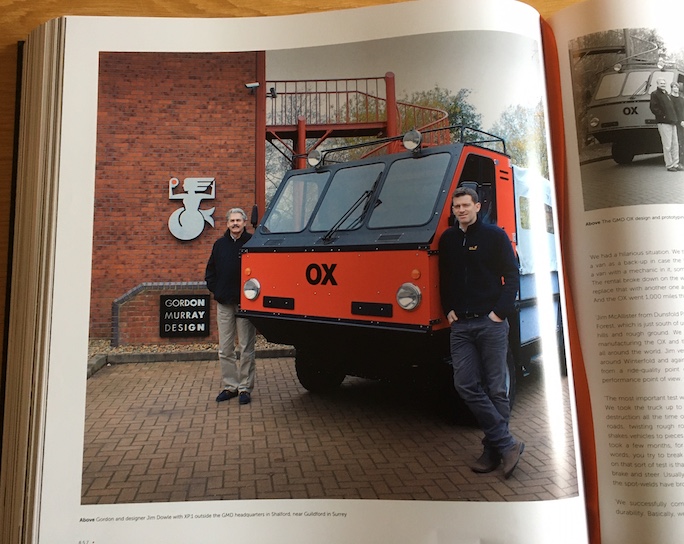

Gordon Murray Design Limited was established in 2007 and the final 130 pages of the book are devoted to its products. Actually, “products” is a misnomer as the designs have not, as yet, been translated into series production, and some will remain either as drawing board exercises or as limited series prototypes. Whilst I admire Murray’s design for (yet) another iteration of the TVR Griffith, I much prefer the lovely little Toray Teewave T32 and Yamaha T40 sports cars. They seemed to me to be far more desirable sports cars than the increasingly cartoonish efforts of premium manufacturers which combine ever more thuggish styling with ever more monstrous horsepower. No student of Colin Chapman (and Gordon Murray is one) would ever be comfortable with cars that are even a millimeter too big or a gram overweight, which explains why Murray’s latest supercar, the T50, is a lightweight despite packing a 650bhp V12. And, far removed from the world of mere fripperies like sports cars are the extraordinary Ox T34 (the flat pack utility vehicle designed for use in developing countries) and the iStream production process. They both challenge conventional thinking but, if they fail fully to be realized, I think that will say as much about entrenched attitudes and vested interests than the quality of the designs themselves.

I once interviewed Murray for Low Flying, the Lotus Seven Club magazine. It wasn’t face to face, just a 45 minute “down the line” conversation and, although I had obviously thought carefully about my questions, my interviewee had no prior notice of what I was to ask him. What normally happens in this type of interview is that we talk for the allotted period and then I spend a lot of time transcribing, then editing and generally making sense of the recording. Hardly anybody speaks in fully formed sentences, or does not stray off the point or doesn’t punctuate a reply with non sequiturs, blind alleys, and self-contradictions. We all do this and whilst our words make perfect sense when we hear them, they often look like nonsense when we read them. But here’s the thing—when I played back Murray’s recording, all I had to do was transcribe it, because every reply was precise, to the point, and delivered in perfectly formed sentences. In that respect alone Gordon Murray was unique in my experience. And this huge book, expensive though it may be, has served only to cement my admiration of Gordon Murray and his utterly extraordinary body of work.

Copyright 2019, John Aston (speedreaders.info)

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter