By the Bomb’s Early Light

American Thought and Culture at the Dawn of the Atomic Age

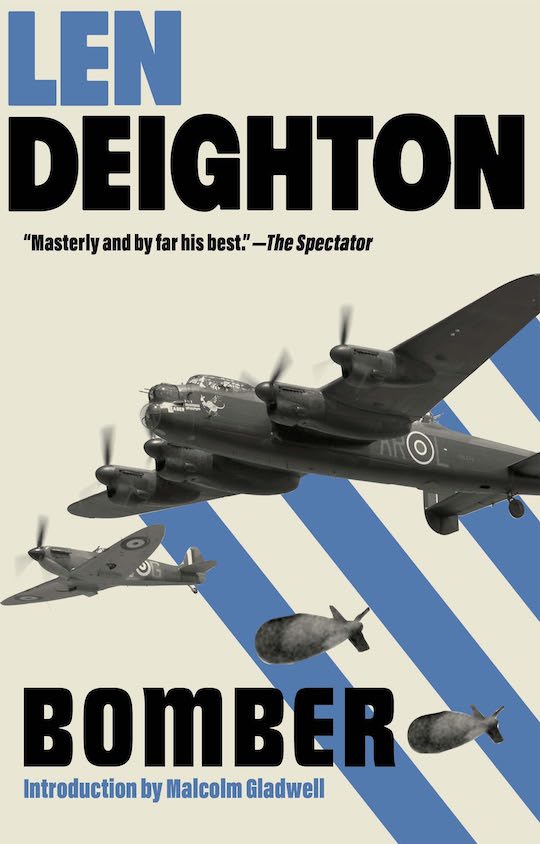

At times, there is a tendency to be more interested in an object itself rather than the effect it might have on the world, both large and small. First published in the mid-1980s and then made available through a university press a decade later, By the Bomb’s Early Light explores an object that was delivered by a pair of B-29s over a pair of Japanese cities in August 1945: the atomic bomb. While there has been much published regarding the B-29 and, perhaps, just a bit less on the atomic bombs themselves, this book is not a technical history of the atomic bomb or the aircraft that delivered it. Rather, it is concerned with the impact of those bombs on American society during the first few years after their use. This is a topic that, surprisingly, has attracted relatively little attention.

By the Bomb’s Early Light is a work of cultural or intellectual history. The bomb itself is little discussed. The impact of the bomb on American life, how it shaped American culture in the first five years after its use, from 1945 to 1950, is examined by professor Boyer. This examination covers a wide gamut of areas in American life, everything from sports to transportation psychology to politics to film and even fashion—yes, the Bikini. Some areas are covered in more detail than others, of course, but the very range of Boyer’s gives much food for thought when considering these years, placing them within a slightly different context than they are often given.

How Americans reacted to and then came to grips with the atomic bomb in this relatively short period is to observe how nations can adapt to rapid change, how their view of the world can almost literally be altered overnight. That only two bombs could cause such massive damage was, of course, startling even to a public imbued with a certain acceptance of mass bombing raids and lists announcing combat deaths from distant battlefields. The initial reaction of most Americans was, perhaps, not dissimilar to that of Paul Fussell (The Great War and Modern Memory, 1975) who summed it up this way: “Thank God for the Atomic Bomb.

The bloody battles of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, with their long casualty lists, the continued fighting in the Philippines, the prospect of an even bloodier future as the invasion of Japan loomed weighed on the thoughts of most Americans during the summer of 1945. The prospect of another year or more of war, even after the defeat of Nazi Germany, seemed unavoidable. That almost literally within days after dropping the two bombs Japan could be forced to its knees and surrender was little short of miraculous. It was science fiction come true.

Whatever concerns there might have been of the many civilians who died in the atomic blasts, the horror and revulsion of the Pacific War brought those Japanese little sympathy among most Americans in the aftermath of the bombs. Few disagreed with Fussell and were thankful for the Atomic Bomb. Only later would there be concern about civilian deaths due to atomic warfare, and only then because those deaths could potentially be those of American civilians, not Japanese.

Why read By the Bomb’s Early Light in the first place? Why read a book that is not particularly concerned with examining and discussing the sorts of things that are either technical or directly related to technology for the most part? When I first encountered this book, it was part of a reading list for a class on American intellectual history. It was new and had attracted much attention within academia. It was among the first to closely examine the era and suggest some things that were, in retrospect of course, rather obvious, but not necessarily so at the time. One need not agree with the author regarding some of his emphases or conclusions, but the chapters tend to be very well written and the research both far-ranging and thorough.

The Epilog to the new edition of the book is, in my opinion, almost worth reading simply for itself. Again, one need not agree or even like what the author advances or observes, but professor Boyer (Merle Curti Professor of History and director of the Institute for Research in the Humanities at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He also wrote When Time Shall Be No More: Prophecy Belief in Modern American Culture.) certainly provides much food for thought. For that alone, I recommend the book.

Copyright 2013, Don Capps (speedreaders.info).

RSS Feed - Comments

RSS Feed - Comments

Phone / Mail / Email

Phone / Mail / Email RSS Feed

RSS Feed Facebook

Facebook Twitter

Twitter